From Our Archives: Nathaniel Mary Quinn

Portrait by Kyle Dorosz. All images © Nathaniel Mary Quinn. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

This interview originally appeared in Musée Magazine’s Issue No. 23- Choices

ISABELLA KAZANECKI: Before we begin to discuss your work, I’m very interested in your middle name, Mary, which is your late mother’s name. Why did you choose to adopt it?

NATHANIEL MARY QUINN: Yeah, Mary is my middle name but as you said it’s my mother’s first name. My mother never had an education. She could not read or write. So, I adopted her first name as my middle name in honor of her. And also by virtue of going to school and getting the degrees I have earned. The diploma says, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, so it’s almost like she went to school as well.

I: You’re from Chicago, right?

N: I am from Chicago. Yes indeed.

I: Do you think growing up in Chicago influenced who you currently are as an artist?

N: Oh yeah, absolutely. In many ways known to me and still unknown to me. Well for starters...growing up on the south side of Chicago. It was a very poor community lacking resources. There was crime, organized crime, drug addiction. My drawings were a way for me to garner respect and protection from local gang members. I learned, early on, the value of my pictures. The other kids in the community who were interested in art would ask for tips from me. Everyone wanted to know how to draw muscle men, so I learned to understand the proportions of the human form so that I could teach my friends. It was my way to garner protection but also connect with my peers, and I was in a way, an educator and a mentor.

I: I know that you were an educator for some years, I didn’t know you started so early on, though. Are you still teaching?

N: No, I was a teacher for ten years, but in 2014 I stopped because my art career gained momentum. I’ll never forget it: April 2014, right before my birthday.

I: Can you talk about your time attending Culver Military Academy in Indiana?

N: Yes. Culver was a military academy founded by men who had served in the military, but it was more so a co-ed boarding school. Mind you, it was not a school that puts you on a track towards the military; maybe 1% of the kids did go to Westpoint after, but most of us went on to college. A lot of the kids were from very wealthy families. This was a way for kids to maintain a sense of decorum, some discipline. We played sports together, ate together. It was a very disciplined environment. The school was built on a tradition of military ethics: bed made, shoes shined, being on time was paramount, having strong ethics and character. It was a phenomenal institution. They had everything. Do you know about NASA? Culver almost had that. But they had equestrian, golf, swimming, hockey for girls and boys, tennis, sailing, and fencing. A lot of people went on to play professional hockey. I fenced. I never heard of fencing before Culver. I was like, man, what the hell is this. I thought it was so cool. You do that cool stance with your hands behind you. You got the sword. It was a stark difference from my upbringing in Chicago.

I: From that point, how did you get into making art, craftwise?

N: The first real education I had...well I’d always been able to draw...ever since I was a child I had this innate ability to draw what I see...it came very natural to me. My first educational experience was with my dad. He too did not know how to read or write, but he had a great ability to draw. He loved drawing cowboys; he liked watching westerns, stuff like that. When he observed that I had this ability, he would sit me down at the kitchen table and we would draw together. He taught me a lot of lessons. He would tell me, “Do not limit yourself to drawing from your wrist. You ought to use your entire arm to draw.” I’ll never forget that; I use that to this very day. I draw with my entire body; drawing is like a dance. Then, he taught me about the notion of erasing. My dad would always tell me, “Never erase a mark that you make. It’s not a mistake, it's an opportunity.” He would take all the erasers off my pencils so there was no option whether to erase. He taught me intention and confidence.

I: At this point, your technique is very unique to you. I’m particularly interested in your technique of layering different mediums (oil, paint, charcoal, gouache) to create one unified image and specifically how this method reinforces your exploration of reality and perception.

N: That’s pretty much on the money. I like working with different mediums, different materials. My favorite with which to work is black charcoal. I think I’m strongest with black charcoal because I loooove drawing. I have an affinity with making charcoal drawings. In the beginning, I was using watercolor. So, I put the watercolor down on the paper. And that dries in about ten minutes. And then I draw on top of the watercolor. And just like my father had taught me, you make your mark with your drawing. And then to get the highlight, I take a gum eraser, and I do my shading with a gum eraser to get that value and the tone changes of the subject on the paper. So when you erase the charcoal, you’re not erasing the stain. You see, it’s part of the drawing process so you can get the effect that you want to get. Now when you erase away a little bit, the charcoal, the color that you laid down with the watercolor, really pops through. So, if I were to put down a yellow ochre on the paper and it dries and I draw a face on the yellow ochre, I erase away to get the tonal values of the forehead, the nose, the lips to see the color kind of break through the charcoal. From then, I begin to incorporate other mediums. You know the oil pastels, the paintstick, oil paint on top of that. That’s what sort of gave rise to this exploration. I use these different materials to create a friction. Pastel is going to pop differently than black charcoal. You put pastels with a charcoal rendering it’s going to enhance the illusion that the charcoal rendering provides. It’s almost photographic. That’s where the skill set comes in. Remember, I’ve been drawing since I’m maybe three, four, years old. That’s many years of practice. So now, I’m more confident in my skill set and I can meld different materials together. Now, the style that I’m known for today is basically, the concept of reduction. You reduce information in order to produce information. Instead of drawing the entire face, you can focus on that which is necessary.

I: Do you find that this collage-like style captures the essence of a person more accurately than photos?

N: When you do traditional collage, you’re using external, physical images, holding those images together to make an altogether different image; there are limitations in that. You’re limited by the photographs. But, when you’re able to manipulate the image as I am, using it as a reference, it gives you an advantage. That’s one aspect of it. I think that the calling together of those different parts that you see in my art functions as an accurate depiction of the complexity of human identity. I think identity looks like that. Noone’s life is seamless. There are some experiences that don’t harmonize with other experiences that may take place in your life. As a result, the construction of your identity probably looks like the work I make. That’s why I kind of enjoy that aesthetic approach in my work.

I: When I look at your work. There are sections that are more densely collaged and then some that are more painterly. Is that an aesthetic choice or more of a symbolic choice?

N: I would say both. I must say, I am very very far removed form where my work could be. I started getting visions about ways of doing that but it takes time. I couldn’t have done it before but I’m starting to get to a point where I’m good enough to do it. And what I mean is getting that same complexity of the face in the body as well. I’ve definitely moved from more of the figurative to the abstract. I’m starting to make breakthroughs in the torso, the arms. This adds more density and complexity. That takes me confronting myself, my insecurities to make those breakthroughs.

© Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Miss Chairs, 2014

© Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Claire Mae, 2014.

I: Thanks for breaking that down. You’ve spoken about the people in your portraits coming to you in visions. Do your paintings always come to you in this temporal way?

N: All of my work is born from a vision. That wasn’t always my practice, though. Before, I would think about something I wanted to make, and then I would pursue making that. Also, my work was primarily predicated on images that reflected these black American lives and politics. As time went on, I found that I developed a broad interest in exploring humanity. I find my work to be actually quite radical. I am really in pursuit of the human life spectrum of people that is not driven by the color of your skin but by the essence of your identity, memory, perception, how you feel; even, how to find a way to deconstruct belief systems and social conditioning. I’m really interested in the essence of the human being, or maybe a part of the essence of the human being. That only happens with the vision. This is not an unusual thing. I imagine most artists work in a similar way. For me, there’s never a time I’m being contrite. I don’t question the vision, I just have a visceral response to them. I set up the canvas, or the paper, depending on what the vision calls for, and I use photographs as a reference point to fulfill every component of the vision. I don’t make a preliminary sketch for the work because the vision is the pre-sketch. When you work with a process like that, for me, not only am I using black charcoal, pastels, or gouache, or paint, but I’m also using empathy and vulnerability as tools as well. You have to mark in the moment and trust the process. You’re sort of painting with your heart as opposed to painting with your mind. Your choices become very intuitive. When you go through a process like that, you’re not even sure what you’re doing. But you know it feels right.

I: I'd like to further flesh out the photography aspect of your work. Could you expand on your use of imagery and found photos?

N: Being that every work starts with a vision—a mental, visual picture—I research and identify photographs that function to satisfy important aspects and components of the vision. The photographs are used as reference material--not merely copying by means of painting and drawing, but using the photographs as a roadmap for the sort of marks that must be made. Also, being that I am working from photographs, which are obviously stagnant, I am able to manipulate the image in accordance to my intuitive desire for the purpose of achieving balance, composition, and form. Also, photographs offer nuances to which the imagination may not initially be privy. Nonetheless, it is important that the most effective photographs are utilized for the sake of the vision. Much in the same way that it is important to hire the right people for various unique jobs. Therefore, if the vision calls for the use of a gorilla's arm, and if I have five different photographs of a gorilla's arm, then there is an "interviewing process," where the right photograph must be selected for the fulfillment of that component of the vision. This is also true within the context of abstraction, where photographs offer certain movements of color and form that would bring about the right balance and form, the right composition and output, resulting in the best possible conclusion for a completed work.

I: I saw in another interview with you by Galerie Magazine that one of your influences is Caravaggio, the 17th century Baroque master. How are you inspired by that work?

N: Caravaggio was very much committed to rendering figures that reflected the time. He tended to reflect working class subjects. I continue to enjoy that about his paintings. He always made more realistic expressions of biblical stories. Prior to him, paintings were more pristine and pure. He was raw. Caravaggio was like the Tu-Pac of his time. You know, I get a lot of my influences just from other artists’ work but also other forms of expression: comedy, film, singers, sports, you know athletes. When you watch a Youtube clip of a basketball clip, you can tell that so many of their choices are intuitive. They’re not overthinking it. They have a more effective way of responding to their experiences and that all contributes to their craftsmanship as a basketball player.

I: That reminds me of a piece of yours, The Comedian, from 2017. Was that influenced by actually looking at comedians?

N: It is. But not literally. I’m a big fan of Redd Foxx. I think Redd Foxx is the greatest comedian ever. I’m also a big fan of Louis C.K. No doubt he’s guilty of the allegations against him. There’s no going back and revising history, that awful history. But also, I think he’s a phenomenal comedian. When I watch Louis C.K. perform, and tell his jokes, it’s not that I’m looking at Louis C.K. and trying to figure out how to make a painting about Louis C.K, but I’m interested in his process, the way he’s able to form his comedic material. That I find quite inspiring. And I think to myself, man I need to try to find a way to more effectively form this majestic, brilliant approach in my own practice as a visual artist. You can’t explore the vast scheme of humanity through one tradition of artistic expression. One must be involved in many traditions of art to express an understanding of the complex thing that is humanity.

I: I was going to ask about whether the composition of your work was more spontaneous or more organized. But from what you’ve said so far about your process, it seems like it’s a little bit of both. Do you think you could expand on that?

N: Absolutely. That’s right. It is a bit of both. If you were to come to my studio, it is very organized. Everything has a place. Everything has a system. There’s a lot of systems in my studio. Culver Academy may be responsible for that. The studio reflects the behavior of the artist working in that studio. It’s from that, though, that I’m able to focus on the more spontaneous natures of my process.

I: What about nostalgia? I sense a nostalgic quality in your paintings, one that emphasizes your past. Can you speak about that?

N: I do a combination of both. My recent show at Gagosian is a combination of pulling from the present and the past. Many of the works reflect memories but many deal with what I deal with today. A lot of the work reflects my insecurities. Or, my doubts. My sense of shortcomings or my struggles with feeling worthy of great things. That is a very present, ever present reality for me.

I: Did you ever feel any pressure early on as a black artist?

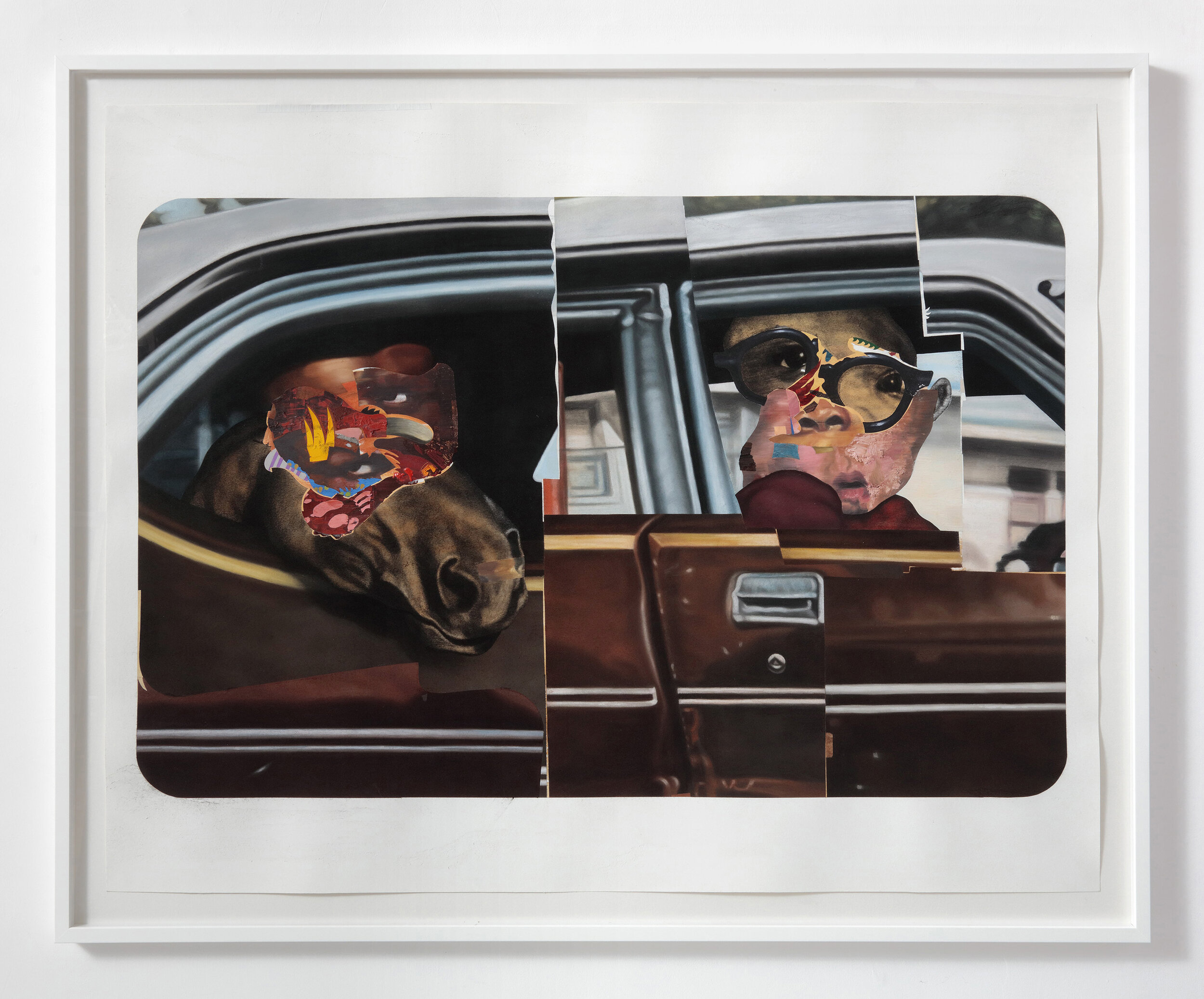

© Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Van Williams, 2016

© Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Terry, 2016

N: Before I had a career, I did. There was pressure to make work about the black experience. At some point, I went to therapy for four/five years. I started exploring my internalized self. I found that to be very liberating. For the first time in my life I felt free to say, I’m not going to be dictated by the color of my skin or the public perception of how I look. I think it’s a really bad thing to allow yourself to be caught up within the confines of your imagination of the other and then find yourself governed by that imagination of the other. Nevertheless, I’m not naive to the nature of my reality. When I walk past police officers I try to make myself look completely non-threatening because I know otherwise they might harm me. For the most part, I don’t feel that pressure any more, of how to be a black artist. The only pressure I feel, is to be a good artist... a great artist. That’s the pressure I feel.