From Our Archives: Pieter Hugo

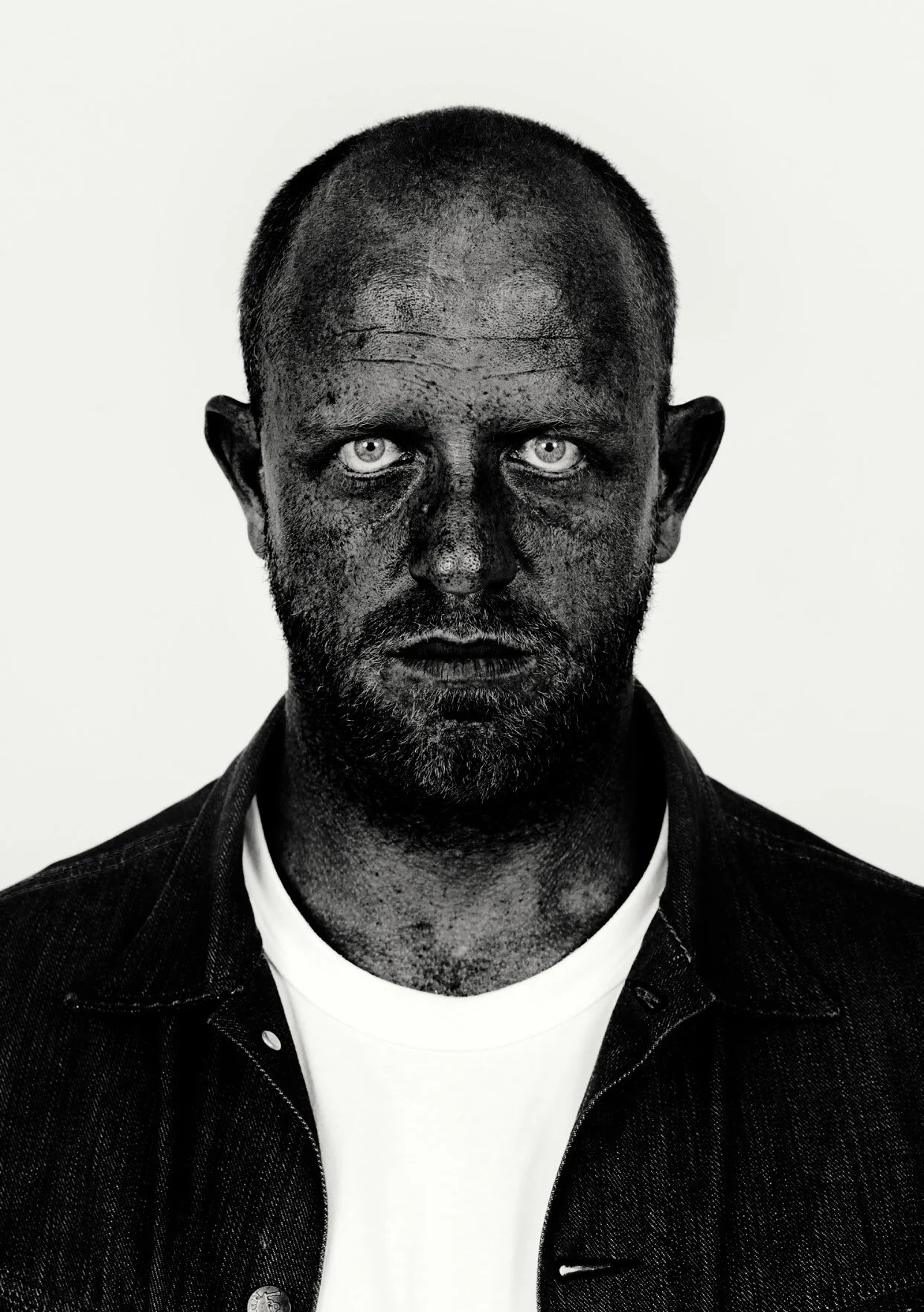

Self portrait by Pieter Hugo. All images from the series The Hyena and Other Men. ©Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

This interview originally appeared in Musée Magazine’s Issue No. 19- Power.

ANDREA BLANCH: So why do you think this work, The Hyena And Other Men, resonated so well with people?

PIETER HUGO: I honestly have no idea. I still wonder about it. When I look at these images it doesn’t feel as if I own them anymore. They’ve entered the public consciousness. I guess there’s something extravagant, impossible, and otherworldly in them.

ANDREA: Why were you attracted to this series? How did it come about?

PIETER: Honestly, who wouldn’t be? The moment I found out about these guys I started making plans to get to them. I heard about them when a friend emailed me an image taken on a cellphone through a car window in Lagos, Nigeria, which showed a group of men with these hyenas and baboons in chains. Later I saw the image used in a South African newspaper with the caption ‘The Streets of Lagos’. And it reported that these men were debt collectors. It featured a hybridization and a conflict between modernity and tradition that I found really interesting. So I decided to try to isolate these men and animals from the spectacle of the performance.

ANDREA: It is a great subject. These hyenas, I’m fascinated by them. Was this a question of power and submission?

PIETER: I think the men and the hyenas had an almost sadomasochistic relationship. The men need these animals to make a living, and the animals have been removed from their natural habitat. They have no way of returning to it, and they wouldn’t survive if you put them back in it. So they’re completely dependent on their captors.

ANDREA: Were they taken to live with the men when they were young?

PIETER: Yes, the men catch them when they’re cubs. So they have this kind of co-dependence which is really interesting, does that make sense?

ANDREA: Yes, of course. I read you said the men smoke weed all day?

PIETER: Yes, they do.

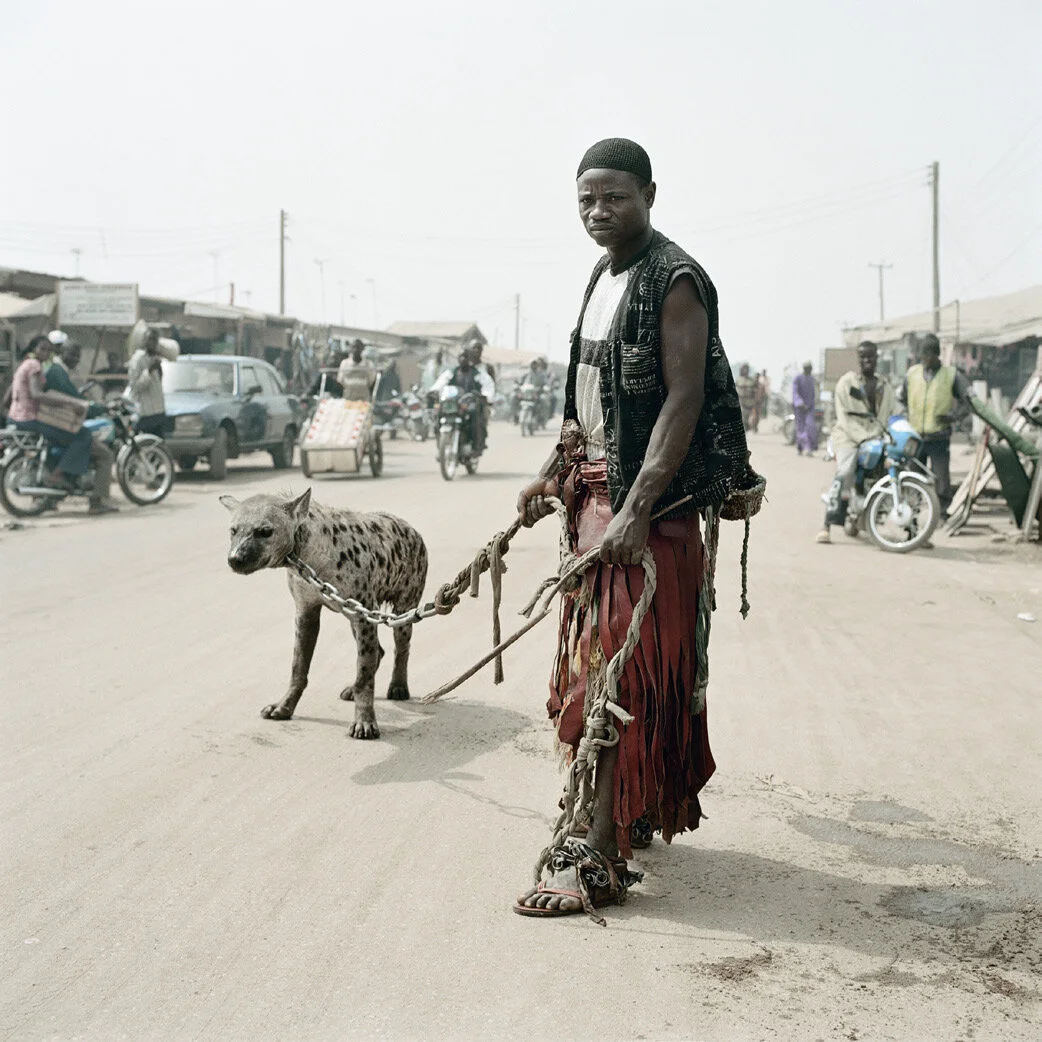

Pieter Hugo, Abdullahi Mohammed with Mainasara, Ogere – Remo, Nigeria, 2007.

ANDREA: Are the animals affected by it too?

PIETER: I’m sure they are.

ANDREA: That might make for a more placid environment.

PIETER: Generally, the men take the hyenas out to perform in early morning and late afternoon. Because it gets so hot in the middle of the day that for a good part of it nothing really happens, the guys just sit around and shoot the breeze and get stoned. The animals lie in the shade and they pour water on them to cool them down, and then when it starts cooling down they’ll go out and have a performance. If you look at these images you’ll see that there are almost no hard shadows. I was there during the Harmatten season when the desert sands of the Sahara blow over West Africa. Everything looks brown and desaturated, muted, and none of the shadows have high contrast in them, and it adds to a certain mood. An apocalyptic mood.

ANDREA: Did you specifically go there during that season?

PIETER: No, it just happened, and after that it greatly informed my palate that I use as a photographer now. I started seeking out working in that climate, in that region of the world, during that season. So to get back to your question about working with these guys, there’s something about the hybridization and the conflict between modernity and tradition that I find really interesting. So I decided to isolate these men and animals from the spectacle of their performance. Contrary to what people might think, getting a hyena or a baboon to stand still is almost impossible. You can try and direct them a little bit, but they’re not that keen on listening to me! So what mostly happened is myself and a performer and an animal would take a walk and I would take a couple of pictures. When I went there I was very broke, so I had almost no film, so I shot very conservatively.

ANDREA: How were you able to converse with these men? Did you have an interpreter?

PIETER: Yes, I had a journalist that I work with who speaks the language. And some men there also speak Pidgin English, so there was some communication.

ANDREA: So I’m wondering how these men responded to you.

PIETER: When I arrived, they were just fascinated by the fact that this guy had flown halfway around the world to come and meet them and photograph them. And they were performers, so they were used to being watched. They enjoyed the process. So did I.

ANDREA: So one last thing regarding the hyena men, is this a work that you feel was fully realized, or is there anything you wish you could’ve done differently?

PIETER: I actually still talk to these guys occasionally. It’s unlikely that I’d go back to make more work there, I think the work’s done. It came at the proper time and place, and that’s part of the reason why it was such a success. For a work to be good it’s got to have its own voice, to be technically proficient, and it’s also got to be relevant. I think this series ticked all those boxes.

ANDREA: And what did you learn from this experience?

PIETER: Hmm, good question. It was the beginning of my 15 minutes of fame, so that was in itself really interesting. It was kind of a transition for me from the photo world into the art world.

ANDREA: I always thought of you as being from the art world, what did you do before?

PIETER: I’ve always been a photographer, but I’m much more interested in sharing in multidisciplinary museums.

ANDREA: Ok.

PIETER: The work we’re talking about, the hyena men series, is work I made when I was in my midtwenties, when I had no money or back up or insurance. But not only did I survive making the work, I actually made good work. There was something very inspiring about that. It laid the foundation for my future work.

ANDREA: You didn’t have a lot of money, I think I read that you only traveled with the hyena men for two weeks?

PIETER: Yes, two weeks at a time over a two year period, a month total.

Pieter Hugo, Mallam Galadima Ahmadu with Jamis, Nigeria, 2005.

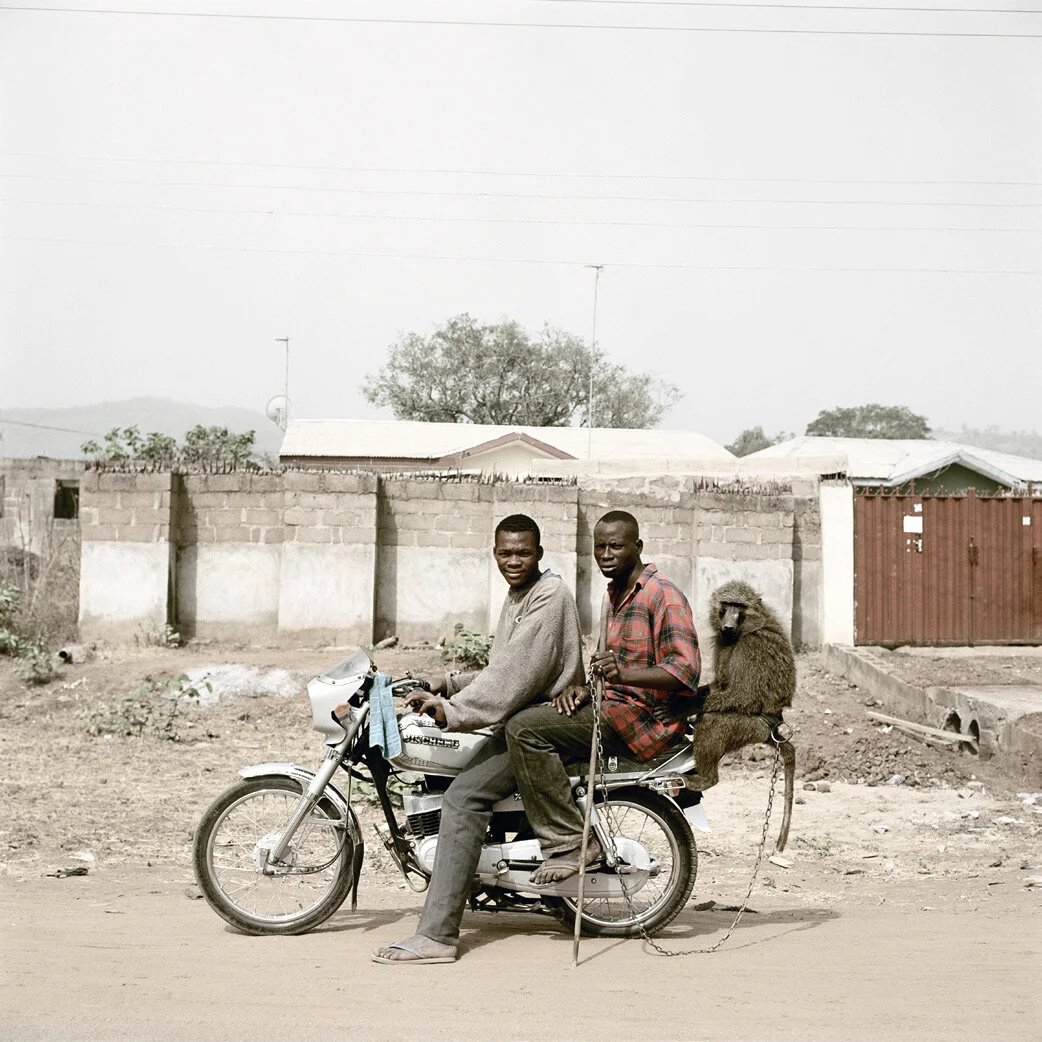

Pieter Hugo, Mallam Galadima Ahmadu with Jamis and Mallam Mantari Lamal with Mainasara, Nigeria, 2005.

ANDREA: A month in total for all the pictures. So do you have more pictures from the second time around?

PIETER: No, I was still pretty broke. All the good pictures were in the monograph, so unfortunately there’s not much more.

ANDREA: What camera did you use?

PIETER: I used a Hasselblad at the time. I actually started with a 4x5, but I realized 5 minutes into day 1 that there was no way I could photograph them with that camera because it just doesn’t stand still long enough. So I used the one I’d brought as a backup camera and I only had 20 rolls of films for the two weeks, so I shot very conservatively. So that was a total of 240 frames over the two weeks, divided by 14 is... I shot about 17 frames a day. That’s not a lot at all.

Pieter Hugo, Alhaji Hassan with Ajasco, Ogere – Remo, Nigeria, 2007.

ANDREA: No, it isn’t! Do you ever think about what the viewer takes away from your photographs?

PIETER: I try not to. At least as far as making the work. I want to follow my own intuition and desires, my own logos. But when editing I very much consider that. Especially when you’re putting an exhibition together or a monograph, then you almost exclusively think of how things will come across, what the arguments are that you’re making.

ANDREA: And what were you trying to convey?

PIETER: Well at the time I was working out of sort of a wanderlust. I think if I redid it now it would be a very different body of work.

ANDREA: Is this one of your favorite series?

PIETER: Yes, but I don’t look at it that often to be honest. Occasionally I see the pictures on screen when I’m sending them to a publication, but when I see them hanging in a collection or in a museum I’m always amazed by them, amazed that I’m the one who made this. All of my works are like my children, and this is one of the children I’m proud of. It feels like so long ago and so removed from me now. But this work has had such a life that it almost feels like I don’t even own it anymore, that it’s entered like some sort of collective consciousness.

ANDREA: Well it’s primal, man versus beast. Did you feel fearful at all while you were there?

PIETER: Well, I was fearful of the hyenas. But of the guys who “owned” them, no, not really. I thought they were protecting me in a way. But I was sort of intimidated by some roadblocks that we had to go through with police and the bribes we had to pay, these issues could be threatening to my sense of safety. I don’t know what its like now but at the time it was outrageous, and I was terrified.

ANDREA: This is beyond someone’s normal experience, coming in contact with these kind of animals. And so people want to know how you felt after you finished the photographs. Did it feel freeing, did you feel emancipated?

PIETER: I think I was just relieved to have survived. I think that something I didn’t realize I used to do, which I don’t think I do as much anymore, is put myself in these situations and survive them so I could feel proud about the fact that I survived.

ANDREA: How do you see yourself in this work?

PIETER: Hmm, there’s an element of machismo and performance and then vulnerability at the same time which I love. It appeals to me, and I guess the fact that it appeals to me says something about me.

ANDREA: This is the definitive series that you’ve done with animals, isn’t it?

PIETER: I actually have animals in my work quite a lot, just not as the main focus of the series. But I photographed wild honey gatherers in Ghana, and I photographed a series called Permanent Error also in Ghana, and a big part of those series was the cattle that lived on an expansive computer dump site. There’s often animals in my work. Like when I do family portraits there are always pets in them.

ANDREA: I don’t recall seeing animals in your last show at Yossi’s.

PIETER: Well, not in the physical work, but in the monographs.

ANDREA: So you’re an animal lover?

PIETER: I don’t know that I would say that I’m a lover, but I would say that I’m intrigued by them.

Pieter Hugo, Nura Garuba and friend with their monkey, Aduja, Nigeria 2005.

Pieter Hugo, The Hyena Men of Abuja, Nigeria, 2005.

ANDREA: And you were born in Johannesburg. Let’s talk about your childhood.

PIETER: I was born there, but I actually grew up in Cape Town, in a middle-upper class family. My parents were quite liberal compared to the environment I grew up in, during the Apartheid in South Africa. But they certainly weren’t political. But I think even from a young age I was acutely aware of the imbalance and travesty that existed in our country, and photography was the means that I used to look critically at it. I think that very much informs my practice. As a photographer where you start out and where you end up are often two totally different places, and you might set out to resolve some conflicts and thoughts that you had about the environment and then realize that that’s just not possible to do, that if anything you’ll make it more complicated.

ANDREA: How did you segway into photography?

PIETER: I was just always into it. I guess I started out as an adolescent, when my father gave me a camera.

ANDREA: And then just kept going. Did you start working commercially and then it evolved into art?

PIETER: I started out as a photojournalist, but at one stage I just found photojournalism too limiting for what I thought I wanted to express.

ANDREA: In what way?

PIETER: With photojournalism, it felt to me like I was working as a propaganda agent. Instead of expressing my own views, I had a list of points from the writer that I would be asked to illustrate. I found this frustrating and disingenuous. I think I had more artistic ambitions than that.

ANDREA: So when you talk about the limitations of photography that’s what you’re referring to?

PIETER: I think that’s partially it, but I also think that people have expectations of photography that are unrealistic. I think it can deliver amazing things, but not necessarily veracity, or an itinerary of facts. It clearly has incredible shortcomings.

ANDREA: I mean there’s many ways to interpret what you just said, so can you give me an example?

PIETER: Like if you really want to know about something you read about it, you don’t look at photographs of it. Photographs are going to inform some nuances, but people put an unreasonable expectation on the practitioners of social responsibility.

ANDREA: You think that even now?

PIETER: I think it depends where you are. You’re in NY and have been able to have these kinds of dialogues about photography for a very long time. This is not the case where I am from.

ANDREA: I’m just saying that this whole argument about whether or not a photograph is truth has been discussed a lot.

PIETER: Within a certain community. But then in parts of the community, when you move away from the coasts of the US, that argument is more or less nonexistent.

ANDREA: The galleries at the Armory Show I saw from South Africa…most of the work they showed was documentary and photojournalistic than art photography.

PIETER: There’s a sort of history that hangs over all South African photography, and that comes out of the Apartheid era. There was a journalistic urgency that people felt needed expressing and anything that did not engage with that was felt as superfluous and frivolous. Even now for museums that show photography, it will always be within a political, historical context. It’s very rare to see work that’s purely concerned with the medium. I think work like that of Alison Rossiter is amazing, but you’d never see it in South Africa because it’s not political. Her work isn’t concerned with representation or with who owns the right to historical representation, which is primarily what South African photography is concerned with. It makes for some interesting work, very strong political work and work with strong convictions, but that also makes for a very limited scope in its expression.

Pieter Hugo, Abdullahi Mohammed with Mainasara, Lagos, Nigeria, 2007.

ANDREA: So, how was your work received there?

PIETER: It got a mixed response, which is good. I think when you’re young, you want acknowledgement. Now more than affirmation I’m interested in the dialogue that my work produces.

Pieter Hugo, Mallam Mantari Lamal with Mainasara, Nigeria, 2005.

Pieter Hugo, Mallam Galadima Ahmadu with Jamis, Aduja, Nigeria, 2007.

You can see more of Pieter Hugo’s work on his website.