Exhibition Review: Woman In Landscape at Deborah Bell Photographs

© William Silano Estate / Courtesy Deborah Bell Photographs

by Madeleine Leddy

From Monet’s Coquelicots and Femme avec ombrelle; to Richard Avedon’s classic cliché of Carmen mid-step in Paris’s Place François-Premier; to Jane Campion’s haunting stills from The Piano of Holly Hunter in period getup, posed next to an enormous grand piano on a hazy stretch of New Zealand shoreline; the motifs of female figure and picturesque landscape have long complemented one another in painting, photography, and cinema alike. Deborah Bell, curator and owner of Deborah Bell Photographs on the Upper East Side, has assembled a small series of works that explores this paradigm across eras and genres of photography.

Bell’s apartment-style gallery is currently lined with original prints that range from British photographer Roger Fenton’s ghostly composition of a young, white-clad woman dwarfed by the Gothic arches of Wales’s Tintern Abbey, to a pair of Bill Silano’s sultry desert pieces for a 1968 edition of Harper’s Bazaar—and beyond, to some even more contemporary pieces. The exhibit is called “Beyond Fashion: Woman in Landscape,” and its situation of pieces dating from the nineteenth century next to colorful prints from the early Golden Ages of American fashion photography in the fifties and sixties makes a statement about the timelessness of both the female form and the earth she walks.

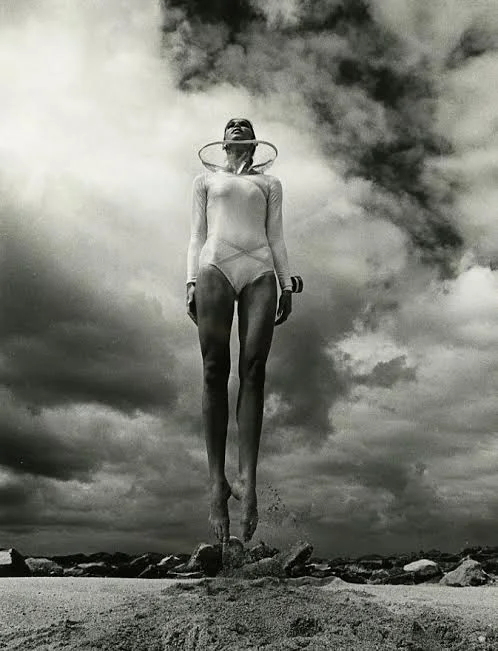

© Bill Silano 1968 Harper's Bazaar

Bell’s acquisition of several nineteenth century works—salt and albumen prints from the repertoires of Fenton and fellow early English photographers, Nevil Story-Maskelyne and Sydney Richard Percy, as well as from French painter-photographer Charles Nègre—was part of what motivated her to curate this group show. Her gallery represents a roster of contemporary photographers (some of whose work, such as that of longtime New York mainstay Marcia Resnick, is also included in the current show), and many of the gallery’s recent exhibitions have been solo shows, focusing on the works of these and other more modern artists. Bell had been waiting for an opportunity to put these antique pieces on display; as her collection grew to include more photographs of women and spaces, she ultimately conceived the idea of assembling multi-era works around a visual theme.

“Woman in Landscape” boasts several photographs by Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus, those two names synonymous with the sixties and the birth—or rebirth—of photography as a fine art form. Another pioneer in un-staged art photography, Harry Callahan, is also featured in the exhibit; Callahan has been featured alongside Friedlander before, as both were avid capturers—albeit with very different perspectives—of their significant others. Four excerpts from his “Eleanor” series, which depict his wife from afar—dwarfed by the towering Chicago skyline, or the expanse of a public park, or the sheer endlessness of Lake Michigan—are arranged in a square on one wall. From these pictures, we learn little of the intimacy that existed between Harry and Eleanor (though she was, without a doubt, his greatest muse), and she appears as a transient mirage, floating between imposing surroundings. But Harry was always nearby to frame and document her, and his decision to place her, delicate and smiling, amid the grandeur of cities and nature speaks to the notion that the woman completes the landscape: a notion that aligns his work with the others on display.

Interestingly, though, it isn’t the Friedlanders and Arbuses, or even the slightly enigmatic Callahan series, that steal the show; rather, it is the four minuscule 19th-century prints at one corner of the room and the gallery—which mark the starting point of the show’s timeline—and, in stark visual juxtaposition, the large, high-contrast prints of Bill Silano’s fashion features for Harper’s Bazaar, which fall towards the end of this timeline.

The nineteenth century photos seem straight out of a Brontë novel. Nevil Story-Maskelyne’s “Portrait of two women, standing and seated” and Fenton’s ethereal figure at Tintern Abbey both seem to be rather grandiose bourgeois portraits: both depict women dressed in white, in rather classic Romantic settings—the English garden in the former, and the Gothic abbey in the latter. Only Percy’s “Gypsy Girls” shows its subjects actively interacting with the landscape—they are coarsely clad and carrying what appears to be hay or fire kindling. The final print, Nègre’s “Woman at the seashore,” offers a mystery to the viewer: the black-clad woman is walking far away from the camera, taken from a distance (comparable to that from which Callahan portrayed his wife) that makes her seem more part of the landscape than within it: she is unknown to us, but just as integral to the scene as the imposing rocks behind her or the ocean to her side.

Over a century passed between the creation of these photographs and Bill Silano’s, and yet something of the grandeur of the female figure, and her integrality to the landscape is reflected in his, just as it is in the Nègre and Fenton prints in particular. Silano admitted, in one of his rare interviews with Glass, to finding inspiration in Surrealism, and this influence is especially evident in the two Harper’s Bazaar prints (both originally included in the May 1968 issue) that depict models in what appears to be a desert or arid beach. One is a color print of a feline-esque model, elongated on the sand and dressed in a brightly patterned day robe; the evocation of the sphinx, a mythological figure referenced by Surrealists such as Dali and Leonor Fini, has been a motif of dream-related art for centuries. The other Harper’s photo, a black-and-white composition of a woman levitating above a similar stretch of sand, sporting a rather fantastic swimsuit with a futuristic plastic collar. She, too, resembles a mirage; a superhuman figure who could only appear to us in a dream.

It is indeed the sheer span of time that “Woman in Landscape” traverses that makes its message so potent. The woman—like the great solid architecture of the cathedrals that served as sets for Fenton, or the immovable expanse of Lake Michigan that did the same for Callahan—is immutable, and many a muse has dominated a landscape for time eternal in both painting and photography. Deborah Bell Photographs’ exhibit comes at a time when women’s agency has, by political upsets around the world, been unduly called into question; these works are a reassertion of the woman, and of her enduring place in art.

Courtesy Deborah Bell Photographs and Hans P. Kraus Jr. Inc.