Exhibition Review: Edvard Munch’s “Experimental Self”

Edvard Munch Nurse in Black, Jacobson’s Clinic, 1908-09 Original: Preserved negative Courtesy of Munch Museum

By Ilana Jael

Until this April 7th, midtown’s Scandinavia House is shedding light on an often unseen side of Edvard Munch with an exhibition of around 50 prints of his work, all on loan from the dedicated Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. While Munch is well-remembered for his paintings, particularly his dark masterpiece The Scream, less attention has been paid to the fact that he also dabbled in the photographic arts, albeit with somewhat less seriousness. Munch’s first camera, which with some of the featured prints were captured, was a simple commercial Kodak, and it is not entirely possible to tell which of his unusual visual choices are deliberate experimentations and which are mere accidents. Many of his images appear out of focus, and some even include the platform used to stabilize his camera.

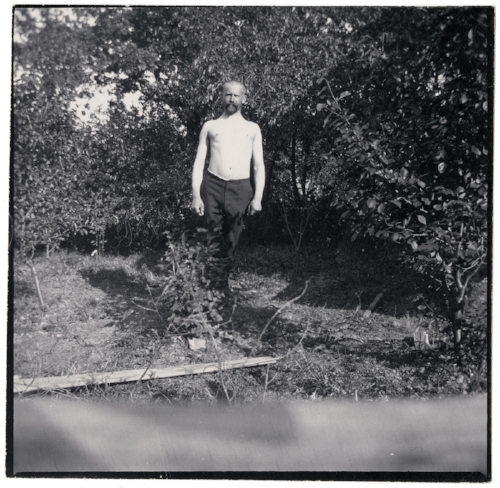

Edvard Munch Ludvig Ravensberg in Åsgårdstrand Original: Collodion contact print Courtesy of Munch Museum

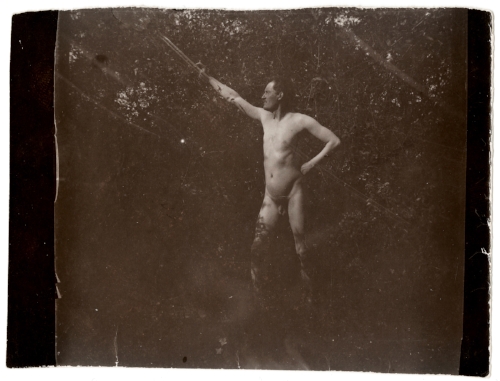

The exhibit is entitled “The Experimental Self” in reference to the notoriously narcissistic artist’s frequent habit of choosing his own image as subject matter of both his paintings and his photographic work. It offers images dating from two distinct periods in Munch’s life, the first running from 1902 to 1908 and the latter from 1927-1932. Among them, one light-hearted shot, 1903’s “Edvard Munch Posing Nude in Åsgårdstrand”, captures the artist posing shirtless in the wilderness with all the verve of a war hero or jungle explorer. In addition, we glimpse him at rest in a rocking chair, sitting beside a bathtub, and in a series of several facial side profile pictures that amusingly call to mind the modern “duckface”.

Edvard Munch Munch’s Dog ‘Fips’, 1930 Original: Gelatin silver contact print Courtesy of Munch Museum

But these playful pre Instagram-era “selfies”, aren’t all that Munch has to offer. Other subjects include the nurse in the hospital he was confined in after a “psychological and physical collapse”, his housekeeper, his aunt Karen Bjolstad and sister Inger Munch, his friend Ludvig Ravensberg, and even his dog. We are also privy to a few of Munch’s photographs of his painted works, but if one, as Munch might have, considers those works as a kind of extension of himself, their inclusion may be viewed as highlighting yet another aspect of the artist’s unending quest to explore and deepen his own identity through his work. The exhibit also features a DVD of Munch’s films, which are played continuously. Like his photography, this footage appears somewhat amateurish in nature, but nonetheless provides viewers with a quaint, charming, though somewhat uneven, tour through various European cityscapes.

Edvard Munch Paintings in the Winter Studio in Ekely, 1931-32 Original: Gelatin silver contact print Courtesy of Munch Museum

But perhaps the highlight of this exhibition are the prints of Munch’s woodcuts, included because of their notable influence by his photographic interests. It is here where the depth of feeling and innovative visual stylings that allowed him to tap into the primal intensity of his most famous work more readily rears its head. In one haunting piece, 1902’s “The Kiss IV”, a figure of a man and a woman physically blur into each other in a shadowy moment that uniquely suggests the melding of two souls into one. Another memorable work, an undated post-1906 “Self Portrait”, is yet another monument to the artist’s evident self-concern. But the particular juxtaposition between pitch-black background and light, sketchy foreground gives his countenance an eerie, almost ghostly resonance, interpreted by the curator as an effort of Munch’s to memorialize himself before his death. Over 70 years after he is gone, Munch’s reflection on his own mortality strikes a modern audience as far more poignant. Perhaps all explorations, of ourselves and of the world around us, would be more aptly undertaken given the knowledge that we all only have so much time in which to explore.

Edvard Munch Edvard Munch Posing Nude in Åsgårdstrand, 1903 Original: Collodion contact print Courtesy of Munch Museum

Edvard Munch Self-Portrait in a Hat in Profile Facing Right, 1930 Original: Gelatin silver contact print Courtesy of Munch Museum

Edvard Munch Self-Portrait Wearing Glasses and Seated Before Two Watercolors at Ekely, ca. 1930 Original: Gelatin silver contact print Courtesy of Munch Museum