Family-found footage and experimental photography: The work of Oman Morí

Interview by Nicole Miller

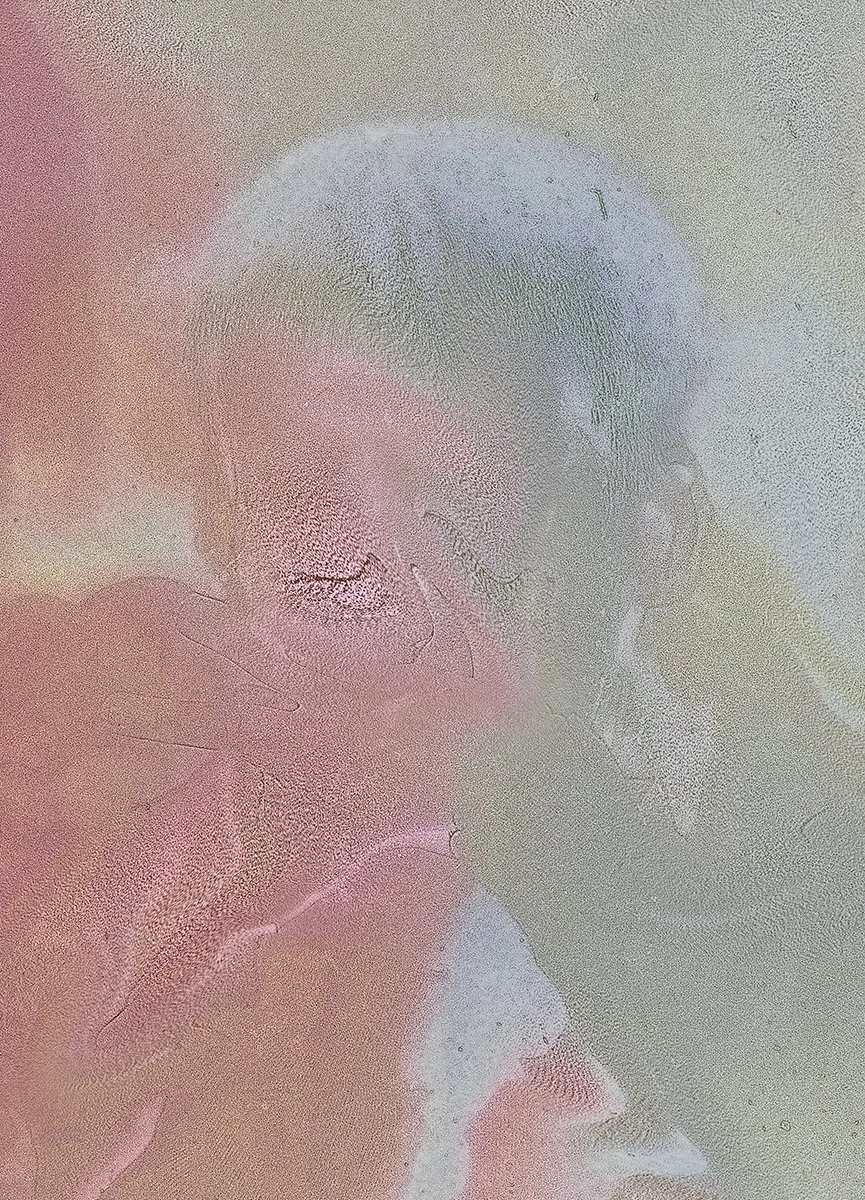

Peruvian visual artist Oman Morí employs the mediums of photography and digital experimentation to delve into the distortion of our personal memories and the camera's role in creating new ones. In his latest work “Schema” he uses family-found footage, in the sense of a forgotten roll discovered and developed after three decades, to explore aesthetically and conceptually this feeling of strangeness with our past.

1. Please tell us about your background in photography.

I recently graduated from the International Center of Photography in New York. I studied contemporary Latin American photography at Centro de la Imagen in Lima, where I'm from. I discovered photography while taking an analog class during my BA in communications. What attracted me was the infinite possibilities it offers to intervene with reality and capture its essence through the lens. I became more interested when I took a lighting class and started to explore how light can create different atmospheres and emotions in a photograph. I got more interested when I discovered stroboscopic photography at the hands of Harold Edgerton and was fascinated by how it could freeze movement in a frame, creating poetic and elusive photographs depending on the speed. My perspective on the medium changed when I took a workshop with Antoine D'agata in Lima. He helped me realize that the camera can help you confront your fears and desires and that this process can be intense and transformative.

2. What are your key motivations in your artistic practice?

My primary motivation is the sense of surprise and discovery that accompanies meaningful and impactful moments in my creative process. Whether it's experimenting with double or triple exposures on a roll of film or manipulating images in post-production to convey a message, I view photography and music as windows into my subconscious. They allow me to uncover hidden messages and emotions I may not have been aware of. This childlike approach to photography has led me into the realm of surrealism, where the power of the unconscious mind becomes a means of revolutionizing our everyday perceptions—a way to have an intimate and personal dialogue with oneself.

3. Where and who do you draw your inspiration from?

I find inspiration in images or artworks that evoke genuine emotions and resonate deeply with viewers or listeners. Artists like Daido Moriyama, who seamlessly integrates the camera into his being, allowing him to explore the human condition through his work, inspire me greatly. I'm also drawn to the post-modern and surreal storytelling of Haruki Murakami, where reality and dreams intertwine without clear boundaries or purpose.

More recently, Leiko Shiga's photography has captivated me, particularly her ability to use the camera to convey the cosmology and mythology of the communities she collaborates with. Her surreal worlds appear effortless, expanding my understanding of the potential of photography. Music, being a significant influence on my work as a musician, connects photography to rhythm, patterns, geometry, and the solitary process of listening to music or composing a song—much like being in a darkroom.

4. In your most recent series, "Schema," you manipulate an old film roll of your father's that contains family portraits. How did this personal element inform your work?

The personal element was the foundation of my project. During my time as a journalist at Centro de la Imagen in Lima, I interviewed Jacky Parisier, an Argentine photographer known for her work involving the discovery of old, undeveloped films in flea markets. These films revealed beautiful, unseen images from decades past, distorted by the passage of time—tiny time capsules waiting to be discovered.

This concept resonated with me as I began using my father's old cameras and found rolls of film from three decades ago. However, what made this experience personal was that I was the subject in those images, confronting my own childhood. Thus, I engaged in a conversation with my past, using digital processes to recreate and reinterpret those memories.

5. What technical challenges did you face in your experimental process?

Given the intuitive and experimental nature of the project, I occasionally struggled to replicate specific aesthetics. Sometimes, I stumbled upon interesting effects while attempting to recreate processes, while at other times, I couldn't quite achieve the initial layering I did before.

When I digitally manipulate images, the main element I alter is the analog grain. Occasionally, certain scans or effects react differently when it is time to export the file, resulting in changes such as the Moiré effect. This effect creates interference patterns that can distort the image. One advantage is that because this project deals with altering reality, it can be anything, I don’t have to think about the color balance or mistakes in the printing process, but at the same time is difficult to decide for myself the perfect balance that I want, asking my peers sometimes confuses me more because everyone has a different opinion.

6. Please explain how you used photography and sound as a metaphor for the distortion of memories over time.

The concept of time has always fascinated me, particularly how it's a subjective experience, varying from person to person. It's never a linear progression; each individual creates their unique perspective on time and memories. In my latest project, I addressed this through photography's ability to influence and reshape memories, introducing an element of distortion.

Simultaneously, I extracted audio from family recordings and subjected them to various processes, such as delays or altering playback speed. This was an attempt to mimic how we often remember sounds from our childhood—fearful of losing the tone of voices of loved ones who are no longer with us. These memories remain within us, but at times, we need something to bring them to the surface.

I'm reminded of something Susan Sontag once said in "About Photography": "The issue lies when we only remember the photography and not the memory itself."

7. What emotions and messages do you wish to convey to your audience through your photography?

I haven't given much thought to how others perceive my work, largely because it is a personal and intimate process. However, I realize that my images may evoke a sense of nostalgia or childish curiosity. Maybe also to bring to mind the capacity to confront ourselves with photography, and see it as a tool to work on our emotions, like a mirror reflecting our unconscious motivations and fears. It's important to avoid chasing after stereotypical beauty or following compositional rules and trends. Although it can be challenging and ambiguous, it is a utopia.

To explore more about Oman Morí’s work, you can visit his website or Instagram profile.