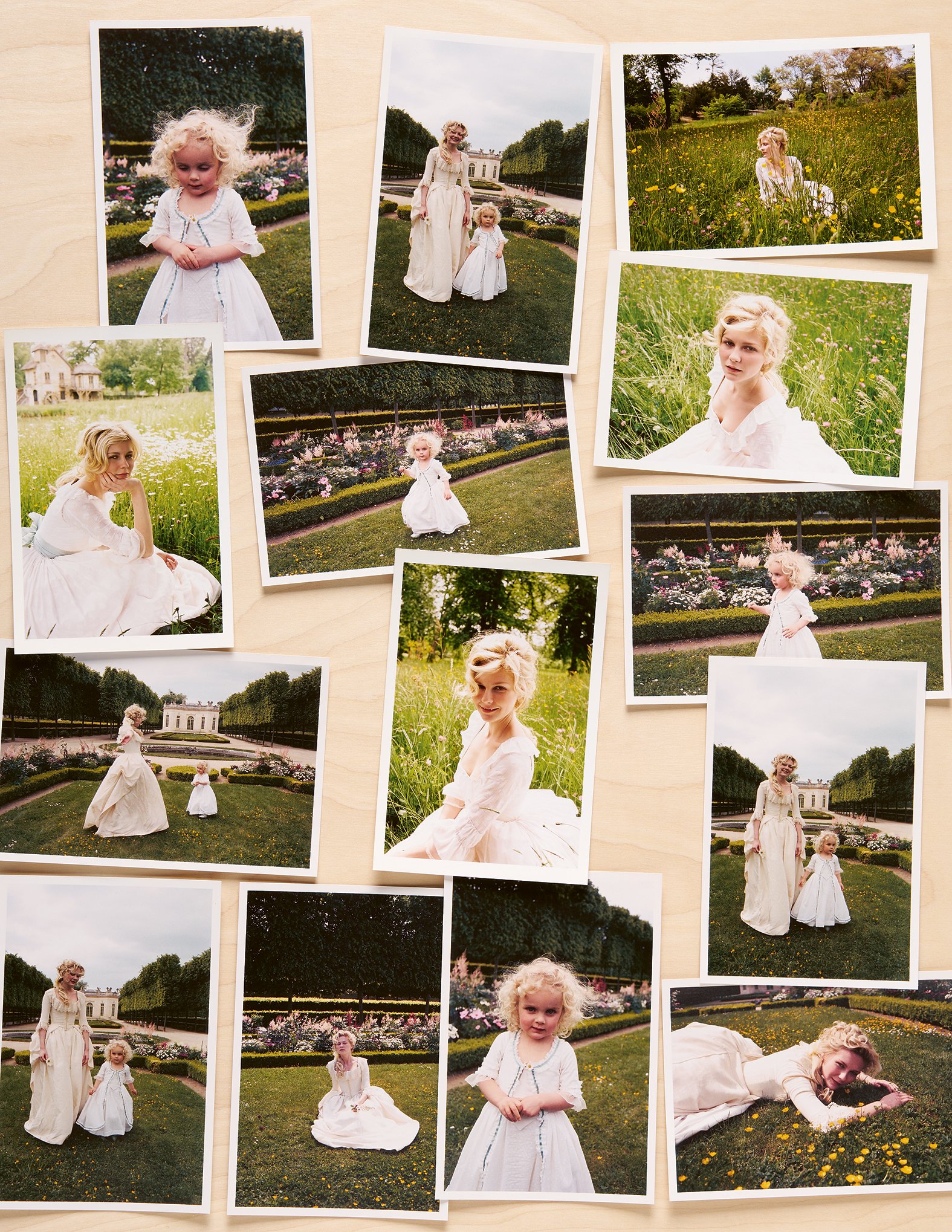

Archive | Sofia Coppola

Andrew Durham, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of Andrew Durham and MACK.

Written by Eloise King-Clements

Photo Editor Ora Heard

Back in 2001, Sofia Coppola's office was photographed for Vogue. The space is a tornado of magazine clippings, doe-eyed faces, strewn manilla folders and pink peonies. To the pearl-clutchers, she explained it was organized chaos—understood by herself—and admitted, “that was in my 20s.” Now, 23 years later, Coppola is giving us the cipher key.

Archive, published with Mack Books, is a tidier display of her process. In her more than two decades of filmmaking, Coppola has carved out an auteurism and a fanbase devoted to her seven films (soon to be eight, with the release of Pricilla in October). Her films hinge on a few main ingredients: a protagonist in the throes of girlhood, a soft mise-en-scène, a gilded cage, and an indie rock soundtrack. While the book maintains Coppola’s visual language, it swaps her trademark delicacy for a grittier peek at the effort required to create her effortless characters. It’s a book for aspiring filmmakers; it’s a book for the romantics and cinefiles, and, if nothing else, for anyone with a thing for Kristen Dunst. Or Bill Murray. Basically, Archive appeals to everyone.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK

With eight chapters for her eight films, Archive, like Coppola, is multi-hyphenate. There’s a lawlessness in the first few chapters which climaxes in a faint, pencil-written letter to Bill Murray begging him to come to Tokyo to film her new movie, and even confessing that she “broke down in tears” while brainstorming other actors if he did not show. This frenzy diminishes as her movies are met with accolades and bigger budgets—her illegible notes become typed and professional—but the photographs, almost all analogue (there’s a brief, but fitting, flirtation with digital for Bling Ring) are a mix of behind-the-scenes and editorial. They all maintain that warm nostalgia, synonymous with Coppola’s style.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK

On the set of her first film, The Virgin Suicides, she invited Corinne Day, of The Face royalty, to photograph. The first chapter reveals hazy shots of the sylphlike girls, Kristen Dunst’s blonde hair billowing over her guileless smile, and gangly teenage boys at Prom. It was an anomaly for a director to host a fashion photographer, but many of her choices at the start of her career seemed to be about distinguishing herself from her male directorial counterparts. In one shot, she’s wearing a resplendent red dress and slides, perched atop a Panaflex video camera. She remembers “making a point of wearing a dress, because that's not what directors ever wore…I was determined to still be feminine while directing.” And in defense of the impracticality, says, “it was the 90s!”

The shots are familiar because Day published them in a magazine after filming, and they became notorious in their own right. The novelty lies within the letters she includes, like the tense correspondence with Jeffery Eugenides, who wrote the novel The Virgin Suicides, when his feet got cold, nervous that she was botching his novel.

Andrew Durham, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of Andrew Durham and MACK

Her films are sometimes characterized as girly, but this volley is usually lobbed by lazy critics who see her visual language-—her films’ soft hues and velvety skin-—as inevitable symptoms of her xy chromosome. In Archive, though, we see just how premeditated she is, meticulously planning the visual narratives. She admits the crew and cast sometimes receive 20 page print outs of her inspiration. She generally references one major artist for each film. The opening shot for Lost in Translation is referencing a John Kacere painting—vis-à-vis Scarlett Johansson's sheer underwear. A Guy Bourdin shot is adjacent to the adorned opening of Marie Antoinette, Jo Ann Callis’ photography is referenced for The Beguiled, and William Eggleston’s Graceland photographs for Priscilla.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

She writes that the idea for Lost in Translation came from a desperation to make a movie about her 20s spent in Tokyo, a recurring daydream of meeting Bill Murray at the Park Hyatt, and inspiration from Hiromix’s photography. Many of the photos feel like they’re straight out of the movie. There are piles of polaroids of the karaoke night—Johanssen wearing the infamous pink wig and Murray in that bright yellow t-shirt (a scan of a notepad shows Coppola’s scribble, “trying to be casual changing t-shirt”) belting into the microphone. There are scans of notepads from The Mercer Hotel with scribbles and snippets of possible dialogue, like, “she fucked her way to the middle,” with a check next to the box. The photos feel like summer camp at the Park Hyatt. Coppola reveals the messy, imperfect side of filmmaking that is often stowed away from public perception. And while the visual experience is of great importance to Coppola, the book does not dissolve into a cacophony of behind-the-scenes, but keeps a gentle pace, one inherent to flipping through photo books, and maintains the romantic and unimposing Coppola aesthetic.

Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK

As our cinema landscape is now dotted with young, female directors, like Greta Gerwig and Emma Seligman, it’s harder to see the glass ceiling. But, when Coppola began her directorial career, the representation of women was scarce. In 2003, she was the third woman ever to be nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars. Although she’s born from directorial royalty—her father is the famed director, Francis Ford Coppola—she over and over has proven herself to be much more than a dilettante daughter. She has offered us respite from the phallocentrism on screen—all her films pass the Beckdhal test (a measurement of representation of women on screen), which many films still fail. She breathed life and complexity to stories of girlhood, and by drawing inspiration from what she knows, she got her foot in the door. Now we must knock it down.