#WHM Gerda Taro + Lee Miller

We’ll be tapping our incredible archives in support of Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day and posting interviews from our Women issue throughout the month of March.

Gerda Taro + Lee Miller the mighty

Fire Masks, Downshire Hill, London, England, 1941 by Lee Miller © Lee Miller Archives

By Ann Van Lenten

Of the stars that mark the pantheon of pioneering war photographers, Gerda Taro (1910-1937) and Lee Miller (1900-1977) share a special place in how they adapted to conflict. They didn’t know one another, but in their careers both were powered by an ambition that blurred the line between adapting to, and creating, circumstance. In order to access the worlds they wanted to work in, they reinvented themselves on the fly. Early on, they changed their names as a business decision and partnered with lovers who helped them learn the camera. Afterward, they struck out on their own, but both produced pictures whose authorship was misattributed to those teachers. Time and again they flouted sexual convention while abiding by social: their friends and lovers functioned in their work lives, yet by all accounts the two were so intelligent, engaging—and good at taking pictures—they alienated few people.

Taro and Miller began covering war with photographic training in the fading “new vision” style—one that looked for fresh perspectives of reality via acute camera angles, close-ups, disorienting horizons, and a love of abstract forms. But by the time each entered her war—Taro the Spanish Civil, and Miller World War II—society and combat had mechanized by a quantum leap, and fascism’s intimidating violence demanded something else artistically. In the brutal and depersonalized conditions of war, both women responded anew by capturing soul, humanity, the lived reality of the everyday. Taro decided to use her camera to fight fascism as a participant, and war pushed her to capture moral, dynamic situations. Miller, with her compartmentalized emotional life and her artistic training, put aside Surrealism’s emphasis on the erotic and subconscious to confront the grim, incongruous truths of WWII’s most gruesome, intense events.

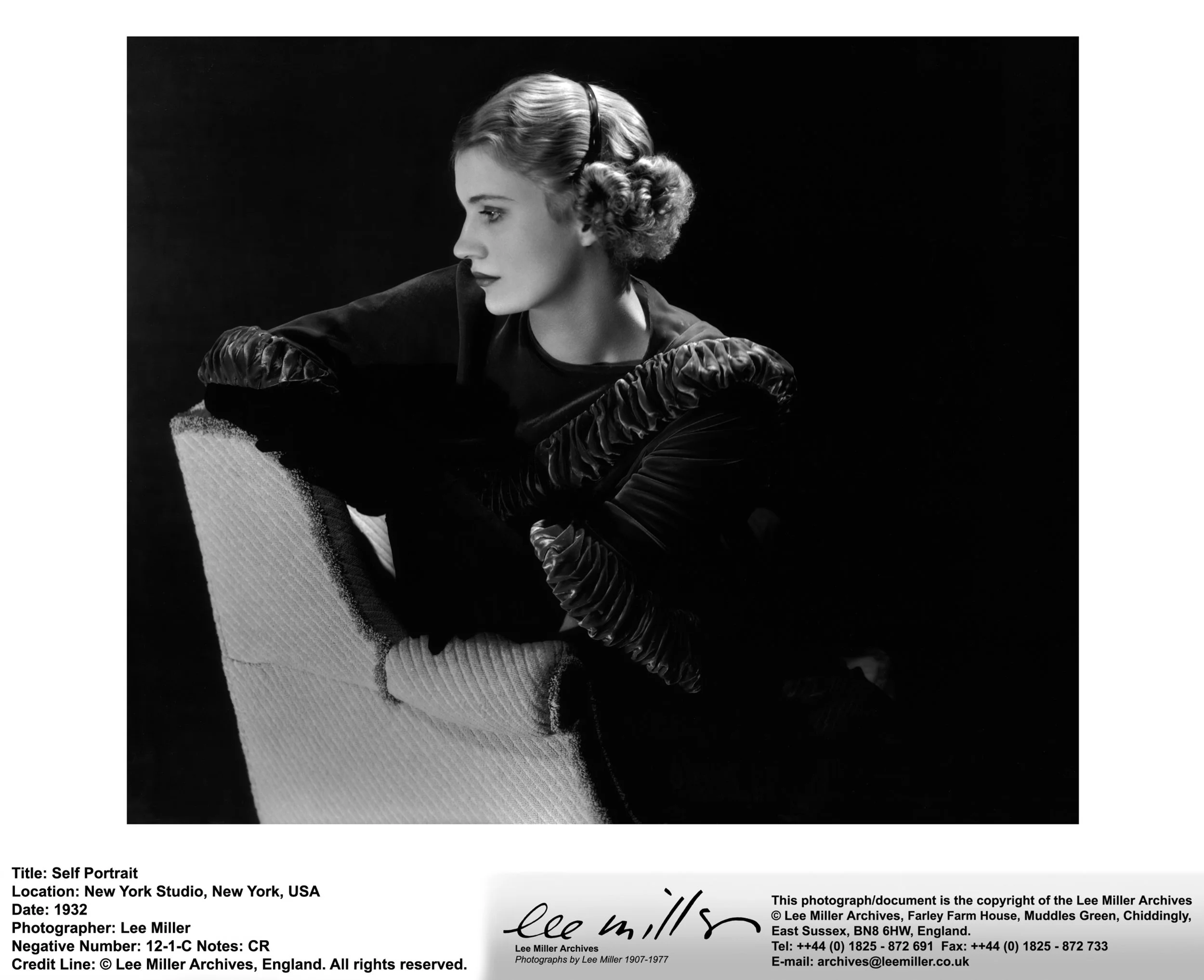

Miller, dead now thirty-eight years, continues to give us photo fever. As of this writing, her archive lists eleven current and upcoming exhibits of her work, shows that celebrate her standout roles as supermodel/It Girl of her day; business partner and model to Man Ray; experimental, fashion, and portrait photographer; and formidable war photographer. In war, arguably the most meaningful manifestation of her ingenuity, I see her well-seasoned visual sensibilities hooking into horror, humor, defeat, tenderness, absurdity, and valor as she covered WWII in Europe.

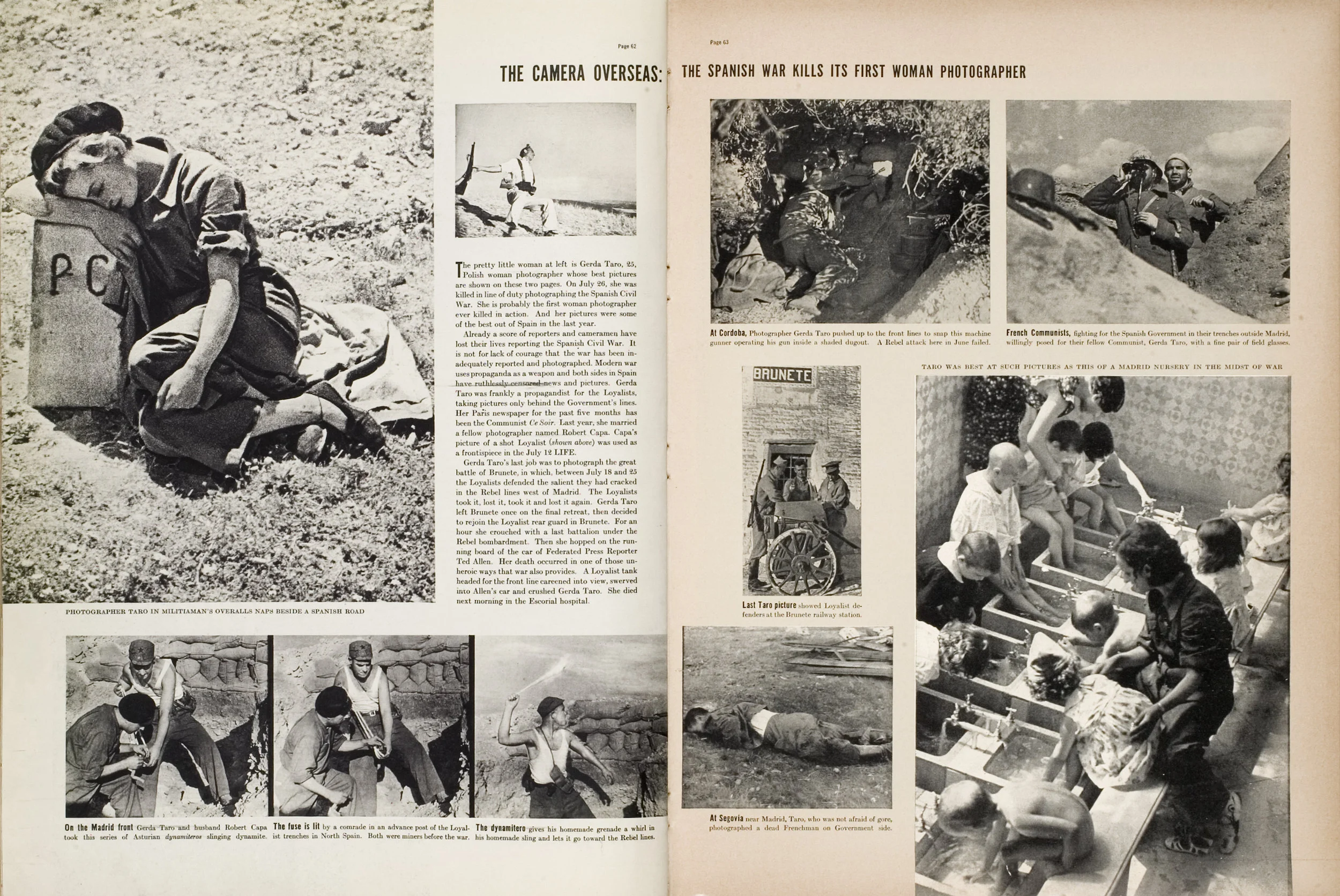

In contrast to Miller, Taro, dead now seventy-eight years, has a cultural reputation that is undeservedly pale despite her vivid pictures of the Spanish Civil War. It wasn’t always so. Her 1937 funeral in Paris drew tens of thousands of mourners who, in solidarity, claimed Taro as an anti-fascist martyr. Giacometti designed her gravesite in Pere Lachaise. For a second she was a heroine, but then history buried her: WWII and its plethora of pictures buried her, in part because her own career lasted 18 months so didn’t yield a large body of work; the death of her family in the Holocaust buried her because there was no one to continue her legacy; and Robert Capa, her partner and boyfriend buried her. He didn’t name her as co-author for Death in The Making, his book of their Spanish Civil War photographs published the year after Taro died. And, by virtue of his outsize fame, she fell into obscurity—Irme Schaber, Taro’s German biographer, says that their working partnership was boiled down to a love story.

Recently, there was a brief blip when the International Center of Photography mounted a 2007 exhibition of Taro’s work—well worth checking out online—but to this day, Schaber’s biography has never been translated into English. Yet Taro helped establish the practice of war photography as we have come to consume it, creating pictures that brim with life, drama, and insight.

Life, August 16, 1937, pp. 62-63. Featuring photographs by Gerda Taro and Robert Capa. Photo © Robert Capa, courtesy International Center of Photography

By the standards of their day, Taro’s beginnings were more outsider-ish than Miller’s. She was born in Stuttgart, Germany to middle class, Jewish parents. She experienced WWI, air raids, food rations, dislocation. In 1933, Hitler was appointed German Chancellor and under the growing domination of the Nazis, Taro became politicized via her boyfriend. In Leipzig, where her family had moved, she got involved with the underground. She was jailed for three weeks for distributing anti-Nazi flyers and posters. By 1934, it was clear enough how inhospitable to Jews the climate was in Germany, and she left, like many others, for Paris.

But Taro had certain advantages as well. She attended Swiss boarding school, then business college. She spoke fluent English and French, a little Spanish, was a great dresser, and charismatically beautiful. In Paris she found work with photographer Fred Stein in the darkroom, then as a photo agent at Alliance Photo. She was poor but resourceful. When she fell in love with Endre Friedmann, a Hungarian Jewish photojournalist, she didn’t just make Endre dress smarter, she organized his office. She didn’t just run the business end of his career, she persuaded him to change his name to Robert Capa and changed hers to Gerda Taro (from Gerta Pohorylle): she grasped that with indeterminate surnames the French press would more likely accredit them. She didn’t just push Capa’s work out, she learned to use a camera herself and with him, went to Spain in 1936 and began to take pictures of its civil war. The activism that got her jailed by the Nazis and prompted her to emigrate to Paris deepened—she was steadfast in her devotion to workers, peasants, trade unionists, and political parties behind the Spanish Republic. In keeping with her malleability, she was given nicknames: the “little red fox” and La pequeña rubia (the little blonde)—un-feminist phrases today, but it tells you something of her appeal

At first in Spain, Taro and Capa took pictures side by side. She sent these to newspapers and magazines under his name—the name she’d given to their mutual enterprise. But soon she used Capa & Taro to label their photos. Then she turned down Capa’s marriage proposal, though not necessarily him, and returned to Spain to continue covering the war. She began sending her pictures out under the label Photo Taro. Regards, Life, Illustrated London News, and Volks-Illustrierte took her pictures. Ce Soir hired her, and by July 1937 she was the only photographer whose images refuted the Loyalist claims to victory in the Battle of Brunete.

Miller’s origins, in contrast to Taro’s, had every genetic and social blessing a body and soul could use. She was American, the daughter of a solid middle-class family in Poughkeepsie, NY. Her father was an engineer, progressive in his beliefs on nutrition and technological progress, and a town notable. As a young working model she was photographed and painted by the most famous artists of the 20th century including Hoyningen-Huene, Steichen, May Ray, Picasso, Cocteau. But modeling for other geniuses didn’t sustain her interest. Like Taro, she went to Paris and wore down Man Ray until he hired her as his assistant, developed her camera skills, and co-created the darkroom technique of solarization. Then she established her own portrait and fashion photo studios in Paris and New York. Vanity Fair named her one of the “most distinguished living photographers” in 1934. In essence, she leveraged her intelligence and appeal as ticket into many a closed club, and once in the door, often surpassed her mentors.

Woman accused of collaborating with the Germans, Rennes, France 1944 by Lee Miller © Lee Miller Archives

The playwright David Hare makes an interesting point about her free behavior. In the late ‘20s and ‘30s, the Surrealists, with whom she was working and socializing, espoused sexual liberation. Miller practiced the very long-leash values they held, much to their anguish, especially Ray’s. She did it again with her open marriage to surrealist painter Ronald Penrose. And again when she took in Time/Life photographer David E. Scherman as lover, mentor, friend. Restless after publishing Grim Glory, her photographs of the London blitz, on Scherman’s advice, she wrote to the U.S. Army and received accreditation as a war correspondent—rare for a woman at that time. She proceeded in the war by her own lights, fueled, not like Taro, by political involvement as much as emotional outrage.

But with Miller, keep looking and certain facts make you realize the complexities behind her golden girl aura. Although this incident was hush-hushed by her parents—and never mentioned by her, her brother identified it—at seven she was raped by a family acquaintance. On holiday with family friends, she was rushed home abruptly and treated for gonhorrea, suffering outbreaks of it the rest of her life. It’s reasonable to suppose that the trauma of the rape stayed with her—especially as she herself never told a soul about it. Her parents sent her to a psychologist however, who instructed her that sex and love were separate.

Another oddity in Miller’s life began a year after the rape, when her father began photographing her nude. Nothing suggests abuse; he also took nude pictures of Miller’s mother, and he photographed his clothed family all the time, as well as keeping written records of their days. He was a gadget enthusiast—he loved Thomas Edison, progress, cameras. Along with his love of the future and adherence to a whole foods diet, he believed in nudism as a way to absorb the sun. But Miller posed nude for him throughout her childhood and young adulthood, and one could speculate that so soon after her rape, this practice contributed to what her biographer Carolyn Burke speculates as Miller’s mind/body dissociation. Such a disconnect would have allowed her to control the male gaze she so often put herself in front of. And it would have served her in times of duress, such as when she was shooting the London blitz, or concentration camps. On the other hand, maybe it shortchanged her after the war when post-traumatic stress disorder made it impossible to reboot her civilian life without drugs and alcohol.

Like her, Lee Miller’s war photography is complicated and various. War shaped her pictures in a slightly different way than it did Taro’s. What persists throughout her body of war photographs is the breath of irony they allow, how it feels as if there is a backstory outside the frame. Her eye could be formal, as her fulsome photo of the nonconformist chapel in London, its mammoth doorway overflowing with rubble, as if it's a child’s plaything or the city vomiting its surfeit of bombing. Her eye could pick up what was monstrous and banal, as the dead German prison guard floating in profile in the canal. All the photos she shot in Dachau and Buchenwald reflect a mind unafraid to look straight on, as when she climbed inside a rail car over a dead deportee to photograph two soldiers standing outside it, looking at the body.

ATS Searchlight operators, North London, England 1943 by Lee Miller © Lee Miller Archives

And her eye sought the absurd, as in her picture of the burn victim, entirely wrapped but for eye and mouth holes in white bandage, a living mummy. Her eye was fluid and powerful, as her dreamlike shot of Hitler’s house burning. It was comical, as with her photo of the sheep patiently standing in the cart, and it was theatrical, as with her pictures of Auxiliary Territorial Service women standing diagonally at the air raid searchlight, or the fashion photo of the two London models wearing fire protection masks.

Above all, Miller was unflinching, as in her picture of the Deputy Mayor of Leipzig suicided with his wife and daughter. Capa shot the same scene but from further back, to allow the entire scene. But Miller went right up to the daughter and mother, lying in a chair and sofa. You get to feast on the bizarre grace of their elongated bodies and the freakishness of their monstrous selves.

Taro’s pictures amount to a dramatic and intimate document of a war that was also a cultural and social revolution, remarkable in the extent of its propaganda, its explicit targeting of civilians, and its reliance on women to fight alongside men. Hers was a brief arc—she went to Spain with Capa in 1936, and died a year later. She believed that with her photographs she could promote the Republican cause and help push back fascism, so her early pictures are fairly propagandistic, favoring stylized posing—a haycart in a field, a militiawoman in profile posing with a gun, a refugee mother holding her infant as she waits for something, someone.

A turning point was early in the morning of May 28, 1937. While Valencia slept, its citizens were blasted by an intense aerial bombardment. Taro went the next day to the city morgue. It was closed, but she persuaded the guards to let her pass. Once through, she turned around and photographed people pressed against the gates outside, waiting to get in to identify their mothers, fathers, children. Once inside the morgue, she took close-ups of women and men dead in pools of blood. Then she went to the hospital and took pictures of bandaged bombing victims in beds.

Now Taro’s mind’s eye began to adapt, becoming quick, immediate—perceptive to the war’s tumult. And because the press was frequently censored, her charms and nerve were key to getting access to the action. Later that summer, her photo of Republican soldiers holding up the captured Fascist flag on their bayonets served as one of the few proofs that the Nationalist propaganda about who was winning at Brunete was a lie. By this point, she was shooting next to fighters, as in her photos of the truck on fire, the close-up of the gentle-faced wounded soldier on a stretcher, her picture of the soldier running to launch dynamite into a building, and one of her best, her picture of a soldier and a man pushing through the door of a burning building, taken from only a few feet behind them.

Lee Miller in Hitler's bathtub, Hitler's apartment, Munich, Germany 1945 by Lee Miller with David E. Scherman © Lee Miller Archives

In short, she had become bold and intrepid. Cynthia Young, ICP’s curator and archivist, says, “I do believe he [Capa] learned a lot from her [Taro]… I think Capa saw and recognized her skills. She had a very aggressive sensibility, a fearlessness.”

Here’s a story about Taro just before she was killed. It speaks to her willpower and wits. She’d spent hours taking pictures from a foxhole in the midst of the ground assault and aerial strafing of Republican forces in the Battle of Brunete. This was July 25, 1937, a setback for the Republican fighters attempting to relieve Franco’s siege of Madrid 17 miles away. Finally, film spent, she was satisfied, invigorated even. She told Ted Allen, the journalist friend with her that she’d got fantastic pictures and could head back to Madrid. In fact, they would drink champagne and celebrate: shortly thereafter she was leaving for Japan with Capa to cover that country’s invasion of China for Life.

In the disorder of the retreating forces there was no room for her or her two cameras. She and managed to get onto the running board of a car, only to be sideswiped by a tank and badly injured. Her abdomen was slashed, her intestines spilled out. At the field hospital, it took her until the next morning to die. But at one point she came to and asked, “Are my cameras OK? They’re new. Are they OK?”

Here’s a story about Miller after she toured Dachau at the end of April 1945. It says a lot about her dissociated state and her intense humanity. She and her partner/lover Life photographer David E. Scherman stayed, along with other allied soldiers, in Hitler’s Munich apartment for a few days. They took many photos. One of the first things they did was bathe—apparently it had been weeks for both—they’d arrived directly from Dachau, where Miller had stood back from nothing in her picture taking.

In Miller’s pictures of Scherman washing off, he sits in the tub naked, his hands on his head, scrubbing his hair. He’s mock-grimacing at the camera. At the base of the tub stand his boots, the soil of Dachau on their soles. On the back rim of the tub, they set up a photo Hitler kept of himself, by his personal photographer. Catty-corner to this portrait, they placed a statue of a classical female nude by Rudolf Kaesbach, perhaps, says her son Antony Penrose, “a snub by LM to Hitler” for his assault of ‘degenerate art.’”

It’s impossible not to appreciate that Jewish Scherman is both cleaning off and enacting what by this point in history is linked with a horrific prelude to death—all in the innermost, private chamber of the figure Miller named the “evil-machine-monster.” In fact, as Penrose notes, “she tilted her camera up to include the shower head. In Dachau the gas chambers were disguised as shower baths.” Implicit in this scene is the illusion that art elevates humanity—classical art could not prevent the Holocaust.

Miller’s take on this episode was that “[Hitler] … became less fabulous and therefore more terrible, along with a little evidence of his having some almost human habits; like an ape who embarrasses and humbles you with his gestures, mirroring yourself in caricature.”

There is no evidence Miller and Taro ever met, nor that Miller was specifically influenced by Taro, although she did form a friendship with Capa in 1944 at the liberation of Paris. Still, Penrose recalls his mother mentioning Taro. An oft-told tale recounts how 27-year-old Miller was nearly hit by a car on Fifth Avenue in New York City, only to be pulled back by a man standing beside her who turned out to be publisher Conde Nast. Penrose says, “I think Lee had a sense of the irony of Taro’s death [by a tank]. … A road accident would have finished Lee in 1927 if she had not been pulled to safety by Conde Nast. I think Taro’s death represented the other polarity of luck.”

Miller may have dodged death that day, but after World War II ended and PTSD destabilized her stormy energies, she was beset by profound depression and alcoholism. Taro was brutally killed in battle, the first woman photographer to die on the job. But she may have dodged the gas chamber herself, and she didn’t suffer the trauma of knowing her entire family was killed in the Holocaust. Ralph Waldo Emerson said “every hero becomes a bore at last,” but Taro—and Miller—merit recognition, not worship. In a way, the two lived alternating sides of the same good luck/bad luck coin. I see their knowing smiles as they wink and toss that coin up, the sun catching heads or tails.

Lee Miller. Self Portrait, New York Studio, USA 1932 © Lee Miller Archives

Note to readers: Lee Miller’s archive wasn’t able to release any more photos than these four. Please go to www.leemiller.co.uk, filter for Germany/France/England pictures and dive in to a body of war photography work that truly reflects her wonderful eye.

A brief, by no means comprehensive, list of reading and watching:

GERDA TARO

- Life Magazine coverage of Taro’s death and funeral: http://bit.ly/1G959J0

- Link to ICP’s Gerda Taro archive: http://www.icp.org/exhibitions/gerda-taro

- Gerda Taro, Fotoreporterin, by Irme Schaber. If you read Italian or German—this is Taro’s biography by Irme Schaber: http://www.amazon.com/Gerda-Taro-Fotoreporterin-Irme-Schaber/dp/3894454660

- Gerda Taro: Inventing Robert Capa, by Jane Rogoyska:

http://www.amazon.com/Gerda-Taro-Inventing-Robert-Capa/dp/022409713X

- Talk by Gerda’s biographer Irme Schaber at the Frontline Club, London, 2008: http://www.frontlineclub.com/new_in_the_picture_with_irme_schaber_the_life_and_work_of_gerda_taro

LEE MILLER

- Link to Lee Miller’s archive: http://www.leemiller.co.uk/

- The Lives of Lee Miller by Antony Penrose, Thames and Hudson, London. Antony Penrose’s bio of his mother, Lee Miller, formed the basis for Carolyn Burke’s.

- Lee Miller: A Life, by Carolyn Burke: http://www.amazon.com/Lee-Miller-Life-Carolyn-Burke/dp/0226080676

- Through the Mirror, documentary about Lee Miller: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1jrxzu_lee-miller-through-the-mirror-1995_webcam