Walead Beshty: The End Game

Portrait of the Artist, Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

Interview by Steve Miller

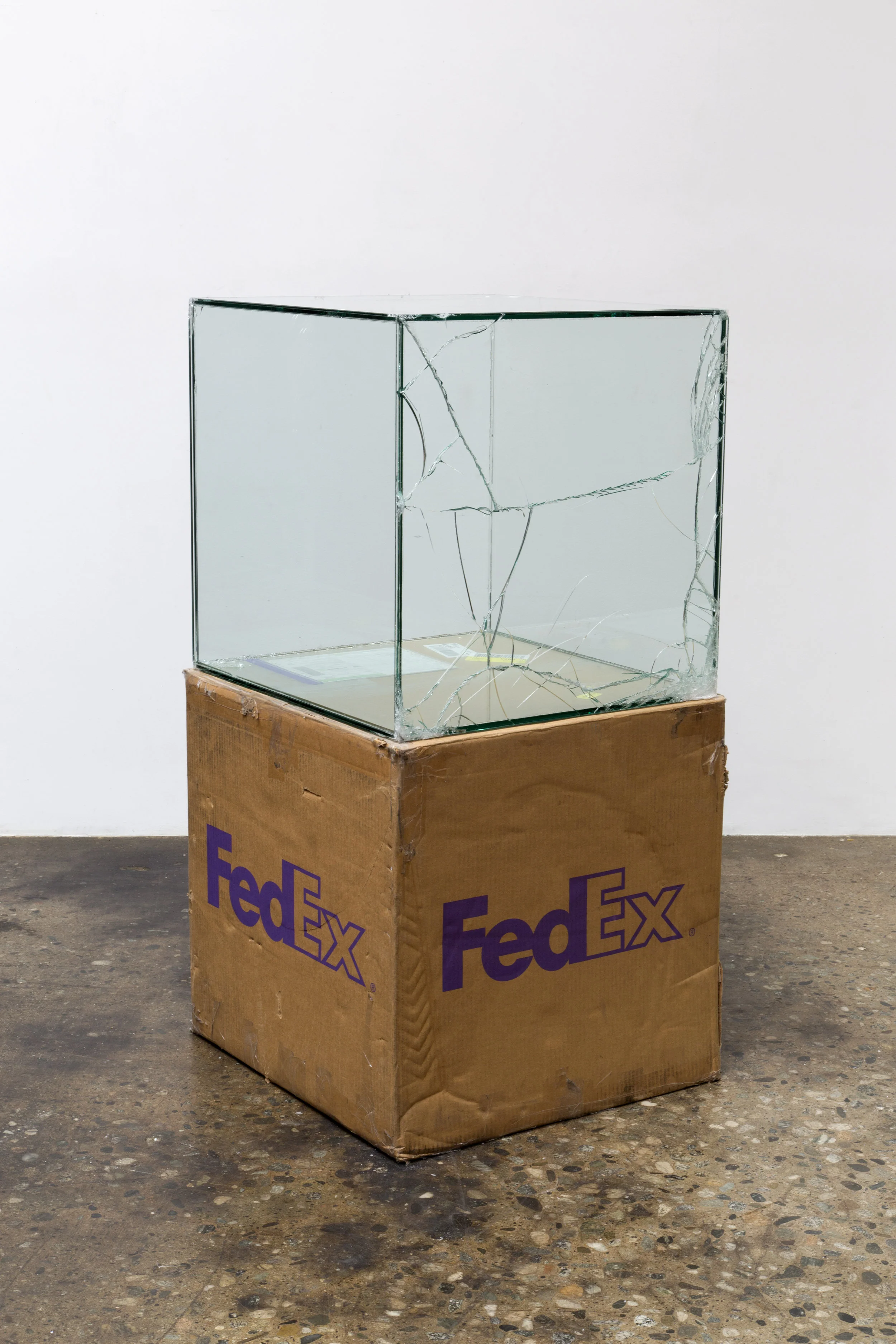

Steve Miller: In your last show at Petzel, I was struck by the variety of your approach and your asking questions about the nature of our collective moment in time. I see your work implying movement, being in motion and physically moving through the world. The most obvious example is your FedEx works (2007– ) where the shipping of the work and its arrival at the final destination creates the image. You have talked about the corporate ownership of a space, the space of the shipping box, and the movement of the work through time is a fascinating twist for me on an intentional readymade. But you've got kind of two dialogues going on here. How did these two worlds, corporate and aesthetic, embrace?

Walead Beshty: I was working on a show in Berlin from afar, and basically had no money for shipping, just my gallery’s FedEx account number. So, I was thinking about FedEx as a limitation on what I would do for that show. I had been thinking about making a sculptural work that was produced by its movement through the world, much like my Travel Pictures (2006/2008) which were photographs of the abandoned Iraqi Embassy to East Germany that were exposed to X-rays while in transit, but I was trying to formulate something that allowed for the work to be more open-ended, a work that was continually in the process of being made by its circulation through the world. As for the corporate dimension, I was aware that standard FedEx boxes are SSCC coded (serial shipping container code), a code that is held by FedEx and excludes other shippers from registering a box with the same dimensions. In other words, the size of an official FedEx box, not just its design, is proprietary; it is a volume of space which is a property exclusive to FedEx. When thinking about the work, its scale and so on, it made sense to adhere to that proprietary volume, because, as a modular, it had a real and preexisting significance in daily life, it was common, specific, and immediately familiar. That is, it had an iconic resonance that a more arbitrary form or shape wouldn’t have.

In this sense, the work occupied a readymade set of parameters. FedEx behaved as it always does, as a corporation that provides a service, and my use of it as an aesthetic tool was a side effect of its normal operation. I think my initial interest was to place the compositional elements of my work into the hands of a disinterested external agent that would act automatically and satisfy its own agendas. The material the works are made of is highly reactive, whether shatter-proof glass, which cracks when force is applied, or copper, which oxidizes when it comes into contact with the bodies of the individuals who handle the objects while in transit. Through the reactivity of the material, the network of forces FedEx corrals to move something from one place to another is also manifest in aesthetic terms, and FedEx becomes a tool for aesthetic production as much as it is a system for the movement of goods. All communication systems formulate the messages they carry in some way, and I think the FedEx works were the first works of mine where I was thinking through that idea.

Rather than thinking in terms of the Duchampian readymade, which is most often understood as operating iconically—as in the appropriation and repositioning of a static thing—I was thinking of readymade systems of production, of using pre-existing active systems to produce a work. No object is truly static anyway, so this opened up broader questions I had about the tradition of appropriation, the way it froze cultural signifiers and reapplied them to other contexts, treated images as dead, static things… The object isn’t treated differently than other FedEx packages, I simply used FedEx to transport an object that registers how the system treated it in aesthetic terms. The result is that the object is constantly changing. Every time the work is shipped it goes through a material transformation. There's either oxidation on the copper or an impact on the glass. But it’s not only that the work changes from point A to point B, but our perception of it also evolves, our experience of the thing is dependent on when it is seen, and who is seeing it.

Because the work is reflective, one is more conscious of lighting conditions, the reflections the works cast in the room, and you see the space, yourself, or others reflected within the work as you view it. What I mean is that it is impossible to see the work in isolation, or as separate from the context it is being viewed in. Now I see the FedEx works as an attempt to make an art-work that was unmistakably intertwined with its circumstance, and continuous with its context. Really, I think of all my work this way, not as isolated things which contain meanings, but as platforms for a field of possible meanings… and by ‘meaning’ I mean the experiences an individual has with the work, or in thinking about the work.

SM: That’s perfect. You have FedEx as kind of a aesthetic producer, which I think now, you've brought these two worlds together, corporate and aesthetic.

Is there irony in the repacking of the work to the final owner because you have to be particularly careful after the initial cavalier shipment to the gallery? Then all of a sudden it's got to act as this special object again, for the collector. That struck me as funny because I imagine the collector who buys the piece wants it just the way it was broken in the gallery exhibition. Or can it just break again? Do you see that at all as part of the discourse?

WB: Well, I think it's interesting because there is an idea of preservation or care that is about trying to freeze a thing in time, insulate it from change. But the meaning of things come from their use, their movement between people, and circumstances they are subjected to. I think the FedEx works disallow a certain impulse to preserve in the term’s conventional sense. Change and the reactivity of materials is central to the work, the work doesn’t exist without it. In this instance, shielding the work from these effects, or trying to restore the work to some ideal state would destroy it. Using an art shipper, or crating the work to protect it, would also prevent the work from doing what it is meant to do. It would change the meaning of the work. It would be arguable whether it is even a work any longer if someone chose a different means of transport.

Legibility on Color Backgrounds installation, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., 2009

SM: Right. But don't you expect that the person who owns this piece will ship it?

WB: They can and should ship it if they want to show it, they should use FedEx, and ship it as is. I mean it's their property, they can technically set it on fire if they want. You can buy a Barnett Newman and use it—thinking back to Duchamp—as an ironing board. But that wouldn’t be acting in good faith. To me, it would be as perverse to use a painting as an ironing board, as it would be to ship one of the FedEx works through an art shipper.

SM: OK. So Friedrich (Petzel) takes the piece of glass, puts it back in the box and ships it to the collector who buys it.

WB: Yeah, that’s it. Furthermore, the provenance of the work is built into the FedEx airway bills, so if someone decided not to ship via FedEx, they would break the chain of provenance. The airway bills also mean I don't have to sign any certificate of authenticity or anything because the chain of shipping labels point all the way back to the studio. It embeds this certification of the work within the object, that was important to me also.

SM: It's great, the concept that your intention is, to let it be exactly what it needs to be as it moves through the world in normal fashion.

You have an interest in the work being partly read as an accumulation of time in movement. This includes the working in the studio, the assembling of the work in the galleries, which makes many players agents in the creation of the works. Meaning, for example, with the copper it's part of an accumulation of marks and the handling by others. And you seem to treat what is, traditionally, a static art object into a flow of continuity.

WB: Art-historically speaking, I think it builds on the readymade tradition as it is manifested in minimalism, conceptual art, and so on, through to institutional critique (although I think that term is a misnomer), rather than acting against some sort of traditional notion of an art-work. One aspect that is often left out of the trajectory of the readymade is labor, so I think it was natural to turn to labor as part of the discussion of the readymade, and art objects in general. The labor of a multitude of individuals is required to make an object appear before an audience, and I try to acknowledge or use that in some way, make objects whose dependence on this system is apparent and unmistakable. All art is collectively produced. I think it's not so much that this flow is specific to my work, but rather I try to not conceal this aspect of art objects.

SM: Exactly. I get that. So, I see aspects of this professional activity you're talking about, morphing into a new kind of artistic performance. And for me that's kind of an interesting hybrid. So, it's like the same blending of that modular FedEx base, the shipping of the box and the creation of the cracks in the glass. Do you consider your work through the lens of the creation of new hybrids or is it something like alternating current or something else?

WB: The way that I think about communication or daily life in general is that it's a performance within constraints. There are a certain set of constraints that bracket our existence, like what is happening between us right now via Skype, we're using a proprietary software, and a public infrastructure which gives our communication a certain structure. For example, visual and audio is privileged by internet communication over the haptic. I think what we are able to express to one another is intertwined with the means at our disposal to do so, you can’t separate one from the other. The kind of communication that Skype or any other platform facilitates directly impacts the way we relate to each other, and each platform has constraints that are specific to it. Art is no different. I try to be sensitive to that. All of these platforms both make certain communication possible, and exclude other forms. At the root of communication is communing, coming together, so these forms are central to our formulation of society and culture, they structure our place in the world, and our place among each other… So, it's not so much that I see it as hybridization in the sense of bringing two disparate things together. More so, I find myself trying to articulate the interdependence and continuity between things, accepting that continuity is a central aspect of communication. That make sense?

Walead Beshty, FedEx, Large Kraft Box, 2008 FEDEX 330510 REV 6/08 GP, International Priority, Los Angeles–Tokyo trk#778608484821, March 9–13, 2017, International Priority, Tokyo–Los Angeles trk#805795452126, July 13–14, 2017

SM: No it makes sense so, you've answered the question. When you look at a Jasper Johns number painting there's the whole notion that systems generate images. And I think that your work embraces that notion of systems generating images in an update that recognizes technological culture.

WB: When I was a student it seemed like the only way to think thoughtfully about making art was through the idea of critique or negation, and that became very restrictive. It made me want to think in other terms, more affirmative terms, not in adversarial ones, to assert a positive outcome rather than simply reveal restriction. It’s not that any of these systems are arbitrary or simply repressive, quite the contrary, they’re meaningful and enabling. The problems arise from the assumption that they are neutral or natural; each is a construction, a tool, and they require constant reevaluation.

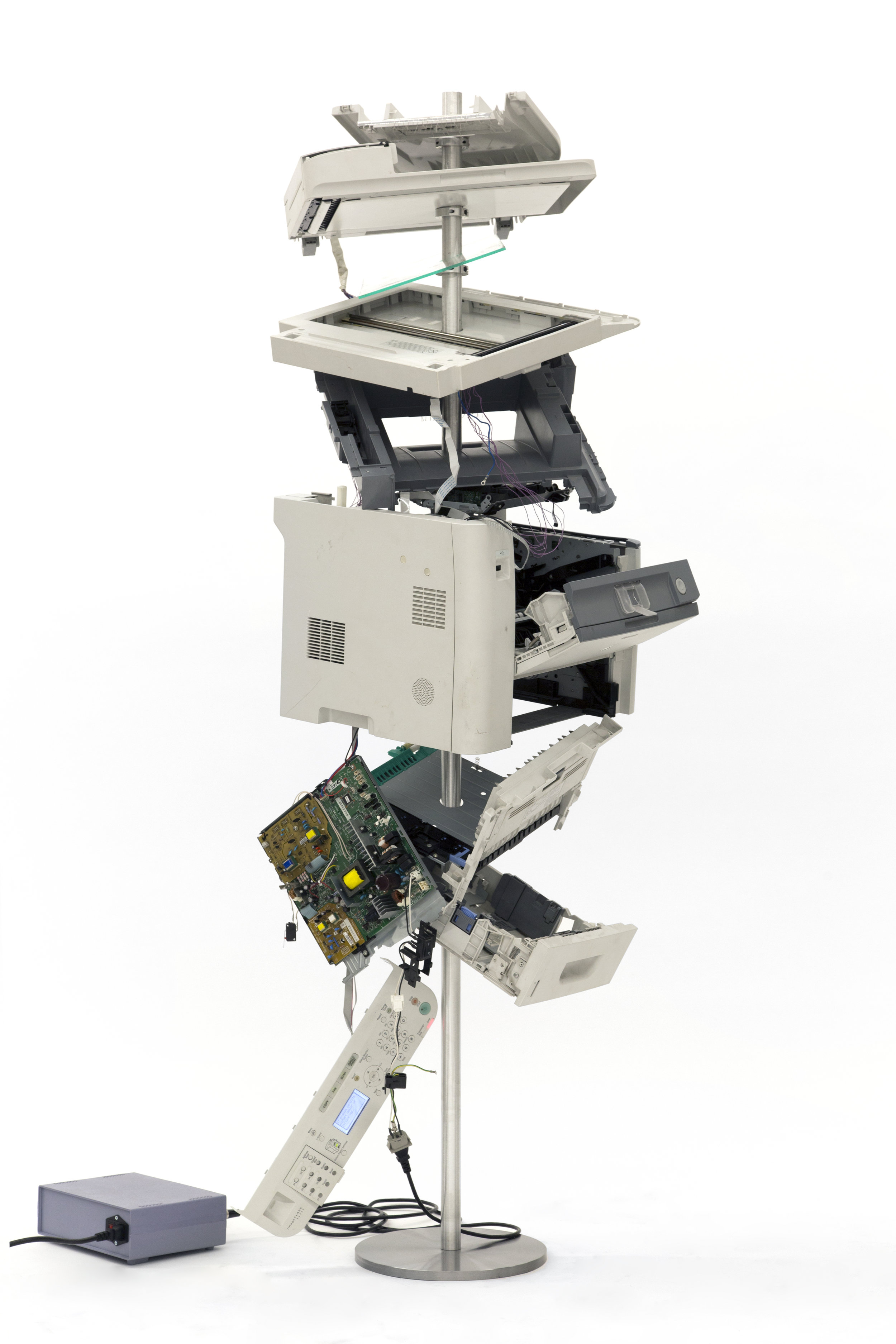

SM: OK. You resurrect or liberate discarded machines, and sometimes what is easily available in the gallery like a copy machine or a printer, and perhaps something like Reinhard Mucha, who thinks in a similar way when he mines the storage room of a museum. In Mucha's installations with the ladders, desks and light fluorescent tubes that he pulls out, he makes a sculpture out of it and when the exhibition is over, that stuff goes back in the closet. So there's this movement from the quotidian to the aesthetic. Your work extends this idea in a new way. I feel the extension of use time, (which would be the initial life of the object and how it was constructed to be used) and moving into this an afterlife which could be construed from my point of view as a kind of heroic gesture. Are you thinking about protecting the discarded and giving extended value, or are you just being practical, or is it both?

WB: I would say it's both; it’s practical in the sense that I’m using what is available, and I’m also trying to extend the value of the materials available to me. We have affection for our objects; we anthropomorphize them and feel intimate with them, and yet treat them as disposable. I think the Office Works rest on that emotional contradiction. I was thinking about an object’s life beyond its prescribed utility. In the beginning, it was making these objects stand upright, like figures in a room, while maintaining as much as possible of their original behavior. Treating them like animate exploded diagrams. It also came from contemplating their existence outside of their intended use. They continue to exist, but not as they were intended: they continue to act, to move, but no longer serve our needs, or maybe serve different needs beyond our original intent.

In a sense, it is the result of thinking about what existence means when it is freed from instrumentalization. We usually hide these objects away when they are no longer desirable to us, bury them in pits, ship them to massive landfills in foreign countries. They persist, but somewhere out of view; in a way, their persistence is a social embarrassment, something we try to hide. I wanted to find a way for them to persist in view in a way that was consistent with how they are personalized and intimate objects; ones we spend a great deal of time with, objects we depend on and invest in. Making them animate figures in the room was a way to do this.

SM: Right.

Walead Beshty, Cross-Contaminated Inverted, RA4 Contact Print (CYM/Six Magnet: Los Angeles, California, April 7, 2016; Fuji Color Crystal Archive Super Type C, Em. No. 112-006; Kodak Ektacolor RA Bleach-Fix and Replenisher, Kreonite KM IV 5225, RA4 Color Processor, Ser. No. 00092174;06816) 2017.

Walead Beshty, Sharp LC-90LE657U 90-inch Aquos HD 1080p 120Hz 3D Smart LED TV, 2017.

WB: The way their current existence is not defined by their intended use is similar to the cut or drilled Television works. The televisions, when cut, make pictures automatically; they are not simply platforms for pictures that are transmitted from somewhere else, but make their own pictures. A generative pictorial logic is imbedded within the objects themselves, and they extend the pictorial logic in unexpected ways when they are ‘misused.’

SM: OK so you're talking about the video pieces. It feels like motion is arrested the way a photograph freezes time, but the moment of looking at your piece is viewing pixels in motion, but the flow of video time is being interrupted. What would have been on the video is now arrested yet, the screen is active and a witness to its dysfunction. I could go around in circles thinking about this and then to keep the circle metaphor active, you drill a physical hole in the shape of a circle into the screen. So, accuse me of a dumb question but have you been accused of circular thinking and is this mental Mobius strip intentional?

WB: I guess there is a circular way that they function, or that their activities are autonomous or self-generated is somewhat circular. LCD screens are common objects that are made mysterious because their interiors are concealed. And by just punching a hole in them or cutting them in half you can see them as simple things, not mysterious floating screens, but as objects. When they are used in a way that is inconsistent with their traditional use, they tell us something about how pictures work. Beyond that, these works extended a line of thought and solved a problem that came from my photographic works. The picture the televisions display is always in motion, flickering and changing, despite being self-generated. They change from moment to moment…still, it’s a kind of picture that's produced in a very simple way that is distinct from its conventional use. There is no mystery in the images they produce, it's very obvious that I simply drilled a hole through it or cut it in half, and that the work is simply what resulted from my doing that. Yet, the pictures that resulted are informative, significant, because they come from the fundamental logic of digital pictures, the raster or matrix of the screen, the pixel, and so on.

SM: But why a hole? It could be a square. You know you could throw it on the floor and break it. I mean there's something about the circle here. I hate to be corny but it just seems to reinforce the way these things work in the world.

WB: I hadn’t thought about why I chose a hole first as opposed to some other shape. Later I cut them in half. I guess both decisions came out of simplicity. Thinking about it now, a hole resonates with the optical. Apertures, and irises are the foundation of the optical; essentially optical images are what is made when you cut a hole in a darkened space allowing light in from the outside. So I think the circle immediately made sense to me for that reason. It was also the kind of cut I could make when I was doing these on my own. First I drilled a MacBook on my drill press, and afterward, when the screen flickered on and the machine continued to work, it got me thinking about how this was a type of picture that wasn’t static, and wasn’t prescribed, a composition made by chance that was dynamic in nature.

SM: Unlike the video screens, the curls are static. They function more like a traditional photograph even though a camera is not involved. How would you view the stasis of a photogram (or photograph) in the context of the active communication of motion which creates the content of your other work.

WB: The stasis of the photograph was something I wrestled with, which is what made me interested in the result of drilling the MacBook, and later LCD screens. Aside from the LCDs, the photographic works have started to address this on their own. Because the photographic processor I use has degraded over time, some of the photographic emulsion remains active even after the processing. There’s no more light exposure other than that produced by the light leaks in the machine, and the pictorial aspect of the work is the result of those light leaks and the irregular movement of chemistry through the machine. So now there are changes that take place over the life of the print, but still it's not as dynamic or variable as some of the other work, instead the work changes slowly. The photograms came out of addressing a certain set of concerns regarding composition and pictorial representation in photographic images, and while I feel distant from those original concerns, the slow change that has happened in the machinery I use has created new possibilities I couldn’t foresee. Making those works is still important to me, but for other reasons, because that body of work has extended far beyond my original intent and has become something new. I find that the most exciting sort of outcome, to have something develop on its own, to exceed its original intent. They’ve always been variable in terms of installation, none have a top or bottom, left or right, but now there is something else happening in those works that extend the initial use of chance operations to make a picture (which is what I was originally interested in) into a picture that evolves over time… I think of my work like a game, and a game isn’t defined by its outcomes, but by its rules and how players operate within those rules, and the richer the game, the more complex and dynamic the outcomes of those rules are. The best games are simple, like Go, but result in a wide set of complex results—exceeding the original conception of their rules. Sometimes games just exhaust themselves, become pointless to invest time in, like tic-tac-toe, which always ends in a draw between experienced players, but sometimes simple games, like Go, continue to produce novel or compelling results even after a lifetime, or lifetimes, of playing it. In a similar sense, the rules I established fifteen years ago for making photographs have exceeded what I thought was originally possible. They could have exhausted themselves already, become redundant, but they haven’t yet.

When the processor finally explodes or the paper is discontinued, I can stop, but I feel obligated to play it until it finds its own conclusion.

Walead Beshty, Open Source installation, Petzel Gallery, New York, New York, 2017

SM: OK so this actually segues into the kind of final frontier here. Your work feels like on some level it's aligned to quantum theory and that energy has a flow of atoms that are always in motion. Matter is not destroyed but transformed, there's always the interconnectivity of relationships that you're looking at. Observing the experiment influences the result. And there's this kind of inner connectivity so, I was just wondering how much you see these principles naturally arise when you actually were thinking about this?

WB: My father was a chemical engineer and toward the end of his life, while in retirement, he got immersed in theoretical physics. We would talk about this stuff, but my math was never strong enough for me to really be able to turn it around in my mind the way he could; I mean, he had a lifetime of math behind him, and I had high school math. I was limited to thinking of fundamental concepts within physics and mathematics through metaphor, which only gets you to a surface understanding. That said, I find it interesting, and I do keep up with scientific research as much as I can through the popular press. Off the top of my head, there is a possible analogy between the conservation of energy and how I think social meaning works. That every time a thing is used it accrues another set of meanings, another set of associations, that meaning cannot be negated or destroyed, it is merely added upon.

SM: Yeah it does.

WB: The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle is another idea that is translatable to an aesthetic context. That observation affects outcome, and that you can either pinpoint a particle’s location, or its speed and direction of motion. I think one can think of objects discretely, as static things, but this obscures other insights. These all seem like vulgar analogies though.

SM: But what I was thinking is that so many things happen to your work by the time it gets observed by the viewer that it has the mass and importance. The object has gathered together enough stuff so that it actually means something in relationship to the culture. So it's the accumulation of a timeline of interconnectivity. I was thinking even the paper which is inert to the eye is moving. You mentioned the imperfection of the emulsion that changes the work over time. Every aspect of what you do made me think that you had your own standard model. Personally, I go back to scientific analogies which are appropriate to your work.

WB: I do have a model of aesthetic meaning that I believe is implicit within the work. I think one of the things it revolves around is a fundamental discomfort with a certain idea of authorship as its traditionally understood. Authorship is always reduced to the singular and I think that there's a legal predisposition toward that, a kind of economic bias at its root. The bias toward property and exclusion, that there is a conventional repression of the awareness that we are a social species that strive for connection, interaction, and engagement, rather than separateness or discreteness. Humanness is interconnection, not division… Agamben has this very nice way of putting it, he describes it as “the being in language of human beings” and it's this being in language, or I would say, being in aesthetics that I am interested in. We live in aesthetic communication and we collectively author aesthetic communication. We all contribute to the shared territory of aesthetic meaning, and connectivity seems an urgent matter both politically and intellectually.

Walead Beshty, Travel Picture Granite [Tschaikowskistrasse 17 in multiple exposures* (LAXFRATHF/TXLCPHSEALAX) March 27–April 3, 2006] *Contax G-2, L-3 Communications eXaminer 3DX 6000, and InVision Technologies CTX 5000

![Walead Beshty, Travel Picture Granite [Tschaikowskistrasse 17 in multiple exposures* (LAXFRATHF/TXLCPHSEALAX) March 27–April 3, 2006] *Contax G-2, L-3 Communications eXaminer 3DX 6000, and InVision Technologies CTX 5000](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5702ab9d746fb9634796c9f9/1539630533705-Z8RT8R0H38R18P3IKUEX/W10.jpg)