Seduced by the Lens: Tabitha Soren

"Just visual eye candy isn't going to get you anywhere"

By Hannah and Cailin Loesch

With a body of work that has captured baseball players and ocean waves, people running and fingerprints, Tabitha Soren is a dynamic photographer with an eccentric story to her success. Perhaps best known for her book, Fantasy Life, featuring photos she took over a span of more than a decade of the 2002 Oakland A’s “Moneyball” draft class, Tabitha has appeared in publications from The New York Times Magazine and Vanity Fair to Canteen, McSweeney’s, and Sports Illustrated. We met up with Tabitha at a restaurant in TriBeCa to discuss her transition from an entertainment reporter to a fine art photographer, where she draws her inspiration, and her method of capturing the famous baseball team’s most intimate moments.

Tabitha Soren, Fantasy Life

Hannah Loesch: You started as an entertainment news anchor, and then you studied art photography at Stanford for a year before becoming a fine art photographer. What inspired the career change?

Tabitha Soren: I wouldn’t say it was as directed as that. I was a television reporter since I was eighteen years old when I went to NYU. I worked at many of the television stations in New York City, and worked at ABC in Vermont and then came back and worked at MTV News and the TODAY show. And all that added up to, in 1996, me finishing the presidential campaign and feeling very burnt out. I felt like I had been chasing after stories for a long time. So I got a journalism fellowship at Stanford—it’s called the Knight fellowship. They pay your way to go to school for a year, and you’re supposed to be a better journalist at the end of it because you don’t have any deadlines. I kind of ended up in the art history department because I liked this professor, Alex Nemerov. Then I ended up in studio art classes and photography classes, and didn’t really go to any journalism or media classes like I was supposed to [laughs]. And so I wasn’t planning that when I went in, obviously—I thought I would spend time learning about making documentaries. And I discovered how few people besides myself watch documentaries, and how expensive they are to make if a company like Viacom or MTV isn’t paying for them. So I kind of decided that if no one was going to see my work, I might as well be an artist.

Tabitha Soren, Running

HL: We’re really into documentaries...we would have seen your work! [all laugh]

Cailin Loesch: But I do feel like it’s kind of rare to find people who are as into them as we all are.

TS: The way one of the A-list directors explained it to me was that fifty percent of his time was fundraising, knocking on doors. And this isn’t Ken Burns, but maybe just underneath Ken Burns. Then he said, if he’s lucky, he gets to take them to film festivals where there’s 12 people in the audience. And I just thought, I had 82 million people watching what I was doing, and they gave me, I don’t know, 200,000 dollars for 28 minutes on MTV. So it was just too much of a jolt—like that just didn’t seem to make financial sense. Or just in terms of energy—I couldn’t sell Girl Scout cookies when I was a kid. I’d never want to be in fundraising. So I really, really fell in love with taking one picture at a time, one frame at a time, and it wasn’t that big of a change because when I was shooting video and I was producing a lot, it was 30 frames per second. So I just went down to one frame at a time and it felt like such a luxury to be able to think of the composition for something so finite.

Tabitha Soren, Fantasy Life

CL: In a way—I mean, you said you would have liked to make documentaries for people—you can take one single photo that has the impact of an entire documentary.

HL: A picture’s worth a thousand words!

TS: Absolutely! I think that there are photojournalists out there, like Lynsey Addario, who do that. I really relished the idea of focusing on a more subtle and emotional truth than “who, what, when, where and why.” So I wasn’t changing to photography to then become a photojournalist. I mean, fine art sounds kind of pretentious and it’s not as if I thought of myself...I didn’t have a preconceived idea of, I don’t know, becoming Taryn Simon, or Marilyn Minter, or any of these other artists who work with photography. I just was doing it because it made me happy. And I think that I’ve been doing it now for fifteen years, and I haven’t been doing interviews, and I haven’t dined out on my other career or used it to get attention. I’ve just really been keeping my nose down and trying to work as hard as possible. Because I think that in America—I don’t know what other countries are like—we don’t really like to reposition someone who’s been successful in another area. So I figured, enough time would go by where people will be old enough to not even have watched any other stuff that I did. And thankfully, because of the internet and YouTube and all of that—like, my kids have no interest in television news whatsoever. They get it from other venues.

HL: A lot of people think that creativity is inherent, rather than something that’s learned. How would you say that studying photography influenced the way you saw the craft, if at all?

TS: It’s my personal belief that everyone’s an artist. Some of us just quit. I think we’re all creative in different ways. Not everybody’s visually creative, but even of those of us who are visually creative, a lot of people quit. In addition to that, you have a whole infrastructure for male artists who are mentored...you know, the older artist sees the younger guy and sees himself in that person and wants to bring him up. I really don’t think women have enjoyed the same sort of infrastructure of how to succeed. I think we’re at a sea change now, but it still will take some time. So what I thought was interesting, to directly answer your question, about studying photography instead of just doing it on my own—which, frankly, a lot of it is trial by fire—was knowing what has already been made. So my work doesn’t look like a lot of what I like. But when I first started shooting, I definitely was a poor man’s Katy Grannan, and a poor man’s Richard Misrach, and a poor man’s Todd Hido. Definitely imitated the people I loved. But it doesn’t look like that now. So I feel like after training and education you just go, Oh! You know, that’s a great idea. I can’t rip that off. That’s someone else’s material, someone else’s territory.

Tabitha Soren, Panic Beach

HL: When I was reading about you, I thought it was interesting that you were a military kid.

TS: Air Force brat!

HL: And you used your camera to kind of remember the people and places from your rapidly-changing life growing up. When you look back on those photos now, do you feel like they captured the spirit and essence of your childhood? How does a lens do that?

TS: Oh, I definitely think they capture the peripatetic-ness of my childhood. I have looked back at them for some sort of inkling of great artist, but it’s not there. It’s sad. [laughs] They’re all very quotidian, all very sort of like those artists, you know, like Taryn Simon, who sort of categorize these people into these sequences of the last meal this person ate, or all these people missing from the Middle East...they’re not even that interesting, it’s basically like, “There’s my blue shag rug! There’s my bed! There’s my desk!”

HL: But they bring back memories!

TS: I mean, you know, at some point, we don’t know whether we actually remember them or remember the picture of the thing, right? So I think that’s a very interesting idea about photography, specifically. But I definitely think that I would not [remember] any detail about the Philippines or detail about Germany without the photographs. It was a really cheap little camera, all auto-focus, and the pictures were all blurry because focusing at that time was so bad, but I’m glad they exist. I’m glad my mother was very much a scrapbooker and an archivist.

HL: Do you credit anyone or anything for giving you your eye for photography?

CL: I mean, you’ve listed a lot of people who have influenced you, at least.

TS: I feel like being a female artist, and especially a female artist with children, and starting a career when you’re older is so challenging and therefore so brave that the main person who influenced my eye was merely the person who gave me the encouragement. And Alex Nemerov, this professor from Stanford who then went to Yale and is now back at Stanford, he’s an art history guy, not a photo-specific teacher. But he made me feel like I had something to say. And I think that my favorite art is not based in narrative, necessarily, but it’s based in a new take on something you’re very familiar with. Sort of like my Surface Tension project mixes icon and index. Like, the indexicality is the artist or whoever’s fingerprints or markings are there, and it’s that thing that we look at and wipe off on our jeans ten times a day—mine happens to be on an iPad—but all that grime on your phone is what I’m taking a picture of. It’s something that’s an easy window into something very familiar, but at the same time, it doesn’t look like anything you’ve seen before. So I felt like Alex Nemerov made me feel like I had an interesting take on the world.

Tabitha Soren, Surface Tension

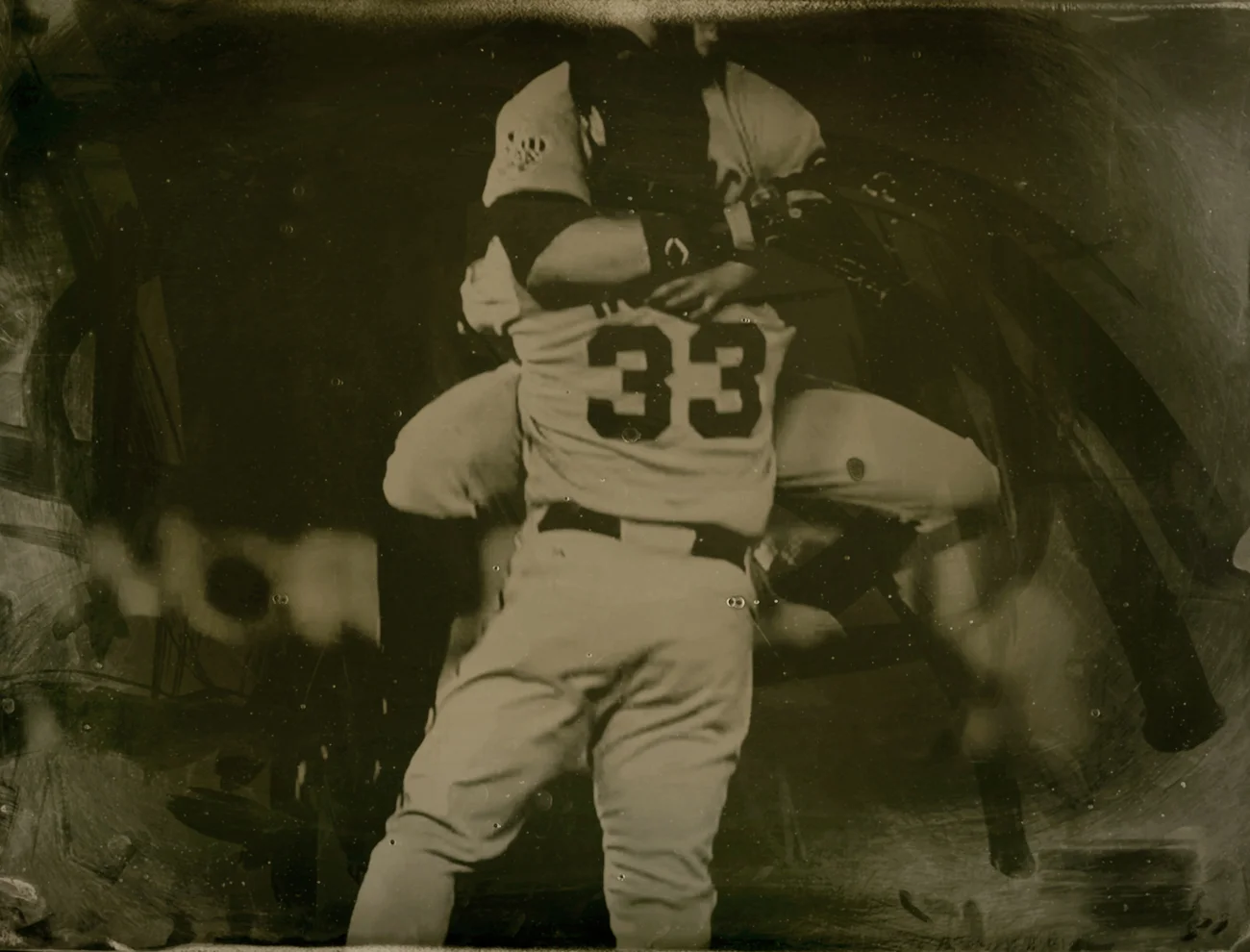

CL: You’re known for spending fifteen years getting to know the famed 2002 Oakland A’s draft class, but I know that you weren’t a big fan of baseball until your husband, who wrote the book Moneyball about the Oakland A’s front office, brought you to the 2003 spring training. And then from there, you got to know the players and spent all those years photographing them in moments no one else really saw. No one else got to see them in that way.

TS: Well, nobody paid attention to it. Because they were following the action of the game. And so I had the luxury of not being interested in the game [laughs]. I mean, I think that’s what a lot of women have to offer. They’re not paying attention to the obvious. They’re paying attention to the moments of transition. And right before I went to that spring training—yes, it’s important that I had access to the team because my husband wrote a book about it—but what I think actually was more influential, which I would mention to your magazine but not necessarily a mainstream publication, is that I had seen Rineke Dijkstra’s SF MoMA solo show. She is all about taking portraits of people in transition. You have all those, let’s say, prepubescent girls on the beach, and then you have the Israeli soldiers who are initiated at age 16 and then you see them after they’re done and, psychologically, the [differences in] the pictures of before and after you serve in the Israeli army are enormous. So baseball isn’t quite as dramatic as that, but that was on my mind. I thought it was going to be more portrait-driven than it ended up, but that’s what made me think, Oh, I have this group of guys, I have access to this group of guys who all started out doing the exact same thing at the exact same time in their lives. And professional sports is so—the lifespan, the career span is so short—that I could, without commiting for my entire life, maybe do the beginning, middle and end of something. So in my mind, Rineke Dijkstra was as important as Billy Beane.

Tabitha Soren, Fantasy Life

CL: They do say it’s difficult to shoot what you don’t know, and that it’s easier to shoot what you’re really familiar with. What was the common ground between yourself and the sport that really helped you to know what exactly you wanted to get out of them?

TS: Striving. I mean, I would love to be one of those people who could sort of do anything half-assed. You know, there are so many unimportant things in the world you don’t actually have to be doing with 100-110% effort, but I’ve never been one of those people. So I identified with them pushing, pushing, pushing, and deciding that they were going to be the exception to the rule, they were going to beat the odds—for whatever reason, that courses through my veins.

CL: And, you know, the players have been—you mentioned the mainstream media—in this case, the players were eventually covered endlessly in the mainstream media. I mean, they made a movie about them a decade later [Moneyball]. You were the one who was there every step of the way, every step of their journey. Do you think that you, as a photographer who saw those moments, had a special relationship with them that you couldn’t have had just by covering their biggest moments as far as the game goes?

TS: Oh, for sure. But you could say that about any situation like that. I did a documentary on the porn industry and I felt like I had a special relationship with one of the actresses just because I was interested in her as a person and I thought she was—like, if her cards were different, she could be running Google. I think that, yes, if you hang around people long enough through the highs and lows, I think I do have a special relationship with them. But I have to say, I mean there’s the Nick Swishers and the Joe Blantons, people who made it to the major leagues, but out of the 21 guys that I followed, only five made it to the majors, and that’s really where the press is. The minor leagues, I mean, I was really like the entire press corp for a lot of the time. So I broke up their boredom, because the routine is very much the same day in and day out. And so if I showed up, they’re like, “Oh, there’s a girl in the dugout! Oh, there’s a girl with a camera!” Or, “Would you get your stuff out of the way” or “Hellooo, Tabitha, the game’s over this way!” I’d be shooting pictures of, like, the spiderwebs on the fence of the locker room or what have you. I think that there were some guys I’ll be friends with forever, but I think that part of that is because I was interested in them as people who had to make a new identity for themselves. And because of just the fact that it’s a job and people have deadlines, sports photographers have to shoot the winning hit and the losing pitch, and it’s all about the victory or defeat. And I was much more interested in all the grey area in between. And you know the luxury of that, [compared to] if you’re trying to file a story with ESPN the next day, you know what I mean?

Tabitha Soren, Fantasy Life

CL: You talk about the winning moments and the losing moments, that, obviously they make as accessible as possible for press to cover. But is it ever difficult when, you mentioned, you’re in the dugout and people want you out of the way? How do you overcome that? Is it challenging to have to kind of get into the middle of it all in a more difficult way than most people do just to be able to capture those moments?

TS: As somebody who moved around a lot, you were probably very good at this, too. You just...I think this was why I was a reporter. In every environment I don’t feel that uncomfortable. Because I’d been put in them—in a new school, in a new neighborhood, I mean whole new regions of the world. I went from the Philippines to the Redneck Riviera of Florida. In Dustin, Florida—I mean, their definition of “female” is so different than mine. I think that just being comfortable in my own skin, and being dropped into a foreign environment, is something that doesn’t take me long to adjust to. And then you just ignore it, if they’re being goofy. I probably made them more uncomfortable than they made me, and then they just relax. I mean they’re dudes, so a lot of times it’s young twenty-something dudes who are hitting on my assistant or, you know, just...I don’t know. And I was in a position a lot of times where I was like, “Okay, take off your shirt!” Or, “Put your outfit back on!” [And they’re like] “It’s not an outfit, it’s a uniform!” Like, “Whatever!” I just made it very clear that I did not know anything about baseball, and I think they found it curious rather than...I just never pretend to know something I don’t know.

CL: That probably makes it more comfortable, too.

TS: Makes them feel superior.

CL: Yeah, comfortable probably because they feel superior. [all laugh]

Tabitha Soren, Fantasy Life

TS: Yeah. And also, they’re kind of also teaching you something as you go along, or what have you. And I frankly made them look at it differently. There’s this picture of mine that I really, really, like: it’s this picture of a door, and it’s got dents in it, and it’s just the equipment door that they had walked by a thousand times on the way to practice. And the game was happening behind me, and the light was shining off all the little dents, and then I had the landscape, the field and the sky reflecting, so it’s blue green, and orange from the sand, with all these dents in it, which to me were like a tally of failures—those were the foul balls they had hit the wrong way! And for that one shot, I probably took like 30 different pictures. And I’m realigning, and I’m stepping back, and I’m stepping forward, and they’re like, what is she doing? You know, they’re totally like, she’s a nutcase. But, at the same time, because I just let them think that of me—a lot of them have surgery, because of the repetitive motion of pitching or catching or hitting, and the calcium deposits build up and they have to have their bone spurs surgically removed—when they had them removed, and they had the specimens and were going to throw them away, and their wives didn’t want them, they would call me and say, “You know, I just had surgery, want these things?”

HL and CL: [both laugh]

TS: And I accumulated them, and there’s this sculpture for the show that I did in Pittsburgh, this totally, kind of scary, wonderfully on-the-nose example of what Americans are willing to do for success. We’re even going to sacrifice parts of our bodies. And they look like little stars; I put it in a vitrine, on dark blue velvet, and then arranged them like a celestial sort of galaxy. They’re creepy, but great. And if I hadn’t developed a reputation as being sort of weird, they would have just thrown them out.

Tabitha Soren

HL: Your work has been published in the New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, Sports Illustrated, among many others, and has been displayed in countless public collections around the country. What advice would you give to aspiring photographers?

TS: Two things that we talked about already. One is, know enough about art history that you’re not imitating everyone else. Because no matter how good that picture is, you’re gonna think of Duane Michals, you’re gonna think of Cindy Sherman. You know, you have to know what’s already been done so that you’re doing something different. And second, have something to say. I don’t think just visual eye candy is going to get you anywhere.

Tabitha Soren, Fantasy Life