When Art Engages Suspicion

Wayne Gonzalez “Peach Oswald” (2001). Acrylic on canvas.

By Andrea Farr

The MET Breuer’s ruminative exhibition Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy proposes art’s unique ability to capture the act of compulsive truth-seeking.

The first of its kind to focus on the ways artists have commented, critiqued, and at times, engaged with the suspicions that persist within Western democracies, Everything is Connected covers roughly 50 years of national crisis and conspiracy. Spanning from the mid-20th century, with the assassination of President John F Kennedy, to just before the election of Donald Trump, this collection expresses art’s unique faculty in embodying the paranoia surrounding imbroglios government activity in postwar America.

A visit to Everything is Connected is not unlike the walk through the actual basement office of a conspirator— it is dimly lit and requires a good amount of exploration. Whether the stairs or the elevator is taken up to the fourth floor space, a voice from inside can be heard in expectation of each entrance. It is the voice of Illinois Black Panther Party leader Frank Hampton, captured by the experimental film group Videofreex in 1969. One month after this interview, he was killed in his sleep by the Chicago Police Department along with fellow Panther leader Mark Clark.

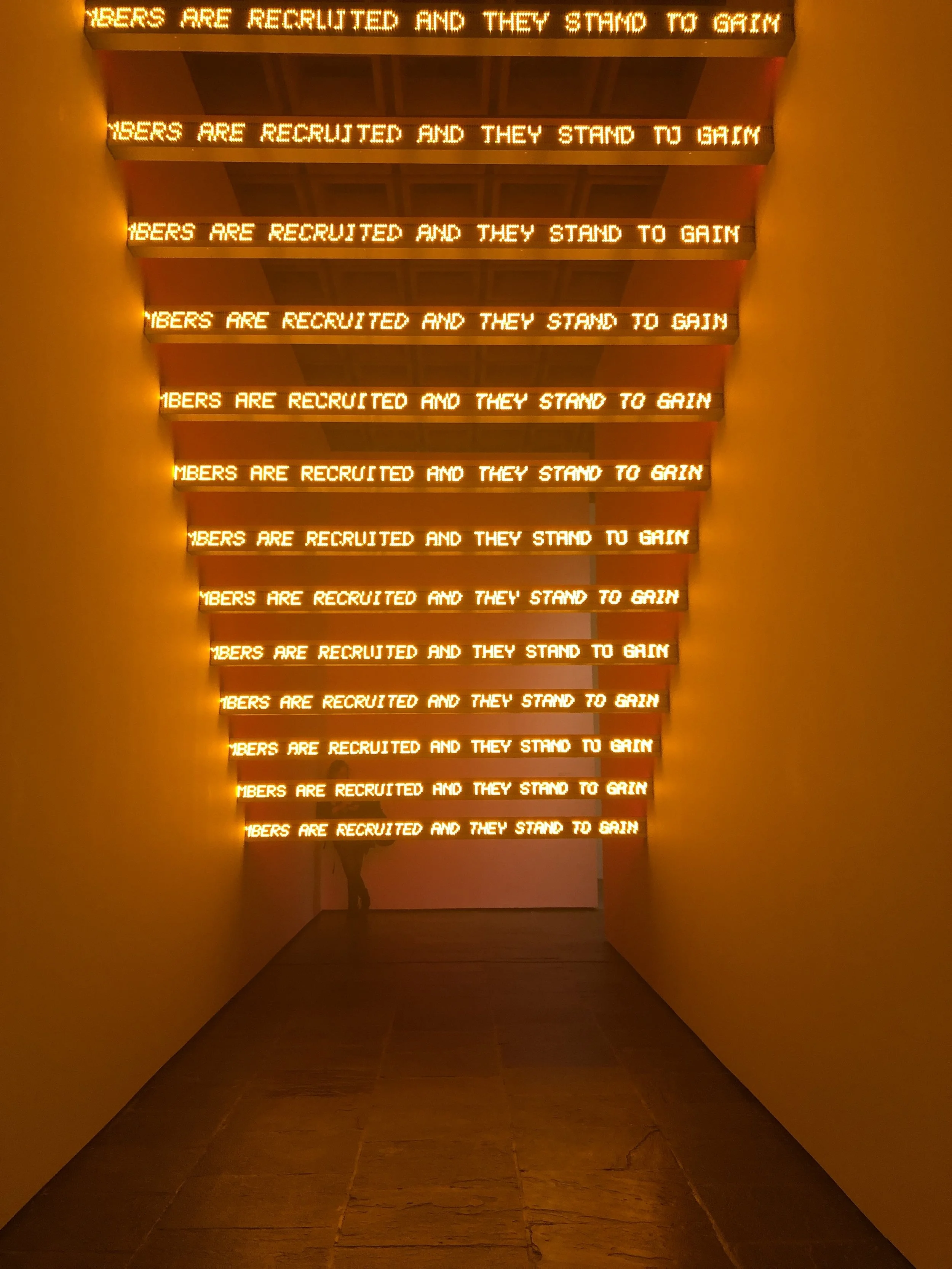

Jenny Holzer “Red Yellow Looming” (2004). 13 double-sided LED signs with red and amber diodes.

The exhibition, hung by Doug Ekland and Ian Alteveer, assisted by Meredith Brown and Beth Saunders, operates twofold. It is split into partnering sections, the first featuring work dedicated to fact-based research and inquiry, many utilizing primary sourced documents from government records to address a feeling of national perfidy in a post-Watergate world, including the AIDS Crisis, the Iraqi War, and continuation of the Civil Rights movement.

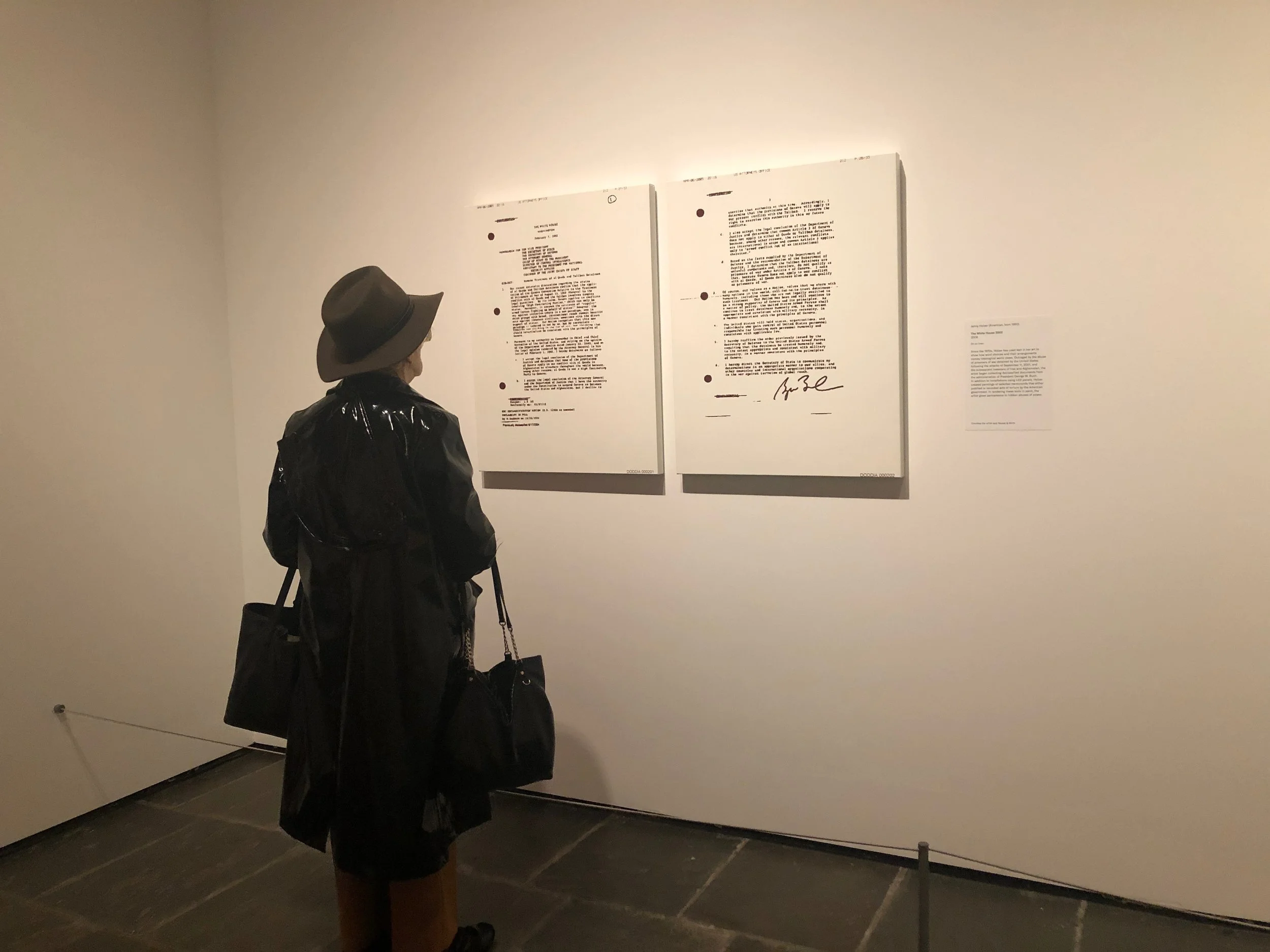

This first portion, two rooms hung with an archival sterility, weighs historical relevance and accuracy over aesthetic innovation. Emphasizing facts and research in their production, these pieces blur the line between functional and artistic, with works like Mark Lombardi’s massive, frenzied, and impeccable 4-year project “BCCI-ICIC & FAB, 1972-91 (4th Version)” etching a web of connections, transactions, and associations between the political forces of the United States and Gulf nations through the Bank of Credit and Commerce International. Relying on documents sourced directly from the source of suspicion, Jenny Holzer uses Bush-era policy publications to construct her appropriation “The White House 2002,” and iridescent LED sculpture “Red Yellow Looming,” both directly utilizing the words of the administration to critically engage with the rhetoric surrounding the Iraq War.

Jenny Holzer “The White House 2002” (2006). Oil on linen.

Walking through, the annals deepen, with Alfredo Jaar’s “Searching for K” and Sarah Charlesworth’s “April 21 1978” breaking from the text-heavy pieces of the first room to visually incite pattern recognition with keen simplicity. Jaar’s “Searching for K,” of 1984, is a collection of photographs, each with a red circle around the head of Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger. Carlesworth’s work operates in a similar way with a series of front pages from newspapers around the world on the day of April 21st, 1978. The text is removed from each page, and an image of former Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro, held in captivity by the Italian left-wing terrorist group the Red Brigades, floats within the blank space of each.

With the immersive transition of Rachel Harrison’s “Snake in the Grass,” the exhibition moves to the second section with a heavier focus on the visceral, abstract, and personal experience of suspicion. Harrison’s installation, a precariously tethered maze of drywall, focuses on a particular section of grass in Dallas, TX, that overlooked the assassination of JFK. It carries the energy of a crime scene, each estranged component as evidence. There is the same photograph of grass in six different shades, a shovel holding a roll of paper, and at the end, a tray with discarded olive pits. None of the dots connect, but instead throw what uneasiness they offer into the remainder of the exhibition.

Alfredo Jaar “Searching for K” (1984), 18 panels, paper works mounted on cardboard (in display) and Sarah Charlesworth “April 21 1978” (1978), chromogenic prints (on wall).

In the second half of Everything is Connected, things go off the deep end. This section, featuring works engaging the troupes and iconography of paranoia, certainly provides more color, medium, and rumination to construct what is a much more individual experience of paranoia. Employing a greater amount of sculpture, the second section gives a renewed existence to conspiracy, letting theories embody forms such as that of a model building, constructed by Mike Kelley. Kelley, to whom the exhibition is dedicated, built the model “Educational Complex” in 1995, entirely from his memories of his childhood school buildings and home in Detroit, to investigate the process and error of recovering memories during a time of trauma. This work is accompanied with other saturated forms, such as Sarah Anne Johnson’s “House on Fire,” an exploration of her grandmother’s experience as a victim of the CIA-funded LSD experiments of the 1950s and 60s. A dollhouse with with small flickering flames and branches poking through the roof, this piece is a scene inspired by hellish hallucinations, each room depicting a particular dizzying terror.

The second half also sees a much more ambitious and attentive use of color. Sue Williams’ frenetic “Mike and Zbigniew” and “Hill and Dale, Black-Ops” are nightmarish brushworks in deceptively optimistic shades of neon, expressing the frenzy and obsessiveness of tragedy.

The split of Everything is Connected into two sections gives a helpful order to the otherwise untethered experience of engaging with the works. It also questions this agency of conspiracy, showcasing categories of engagement with conspiracy as discrete, posing the question of how far form can be pushed before it no longer is truth finding. Comparing painstaking works of analytical rigidity to forms expansive in their ideological reach and aesthetic innovation, this split pensively wonders, how much can be explored until rumination is no longer pointing back towards a truth?

Rachel Harrison “Snake in the Grass” (1997). Aluminum, drywall, wood, latex, acrylic, garbage bags, rope, chromogenic prints, inkjet print, FEGS chart, lamp, polystyrene, tape deck, bottled water, snakeskin, shovel, baking sheet, olive pits, cigar, and hunting traps.

Shovel and paper from “Snake in the Grass.”

Artists have doubtlessly been grappling with these themes far before the five-decade focus of this exhibition, but the scope of Everything is Connected gives specificity to a show that threatens disorientation. It is, however, offset by the geographical array of artists, mostly New York and Los Angeles based, a lack of inclusion that overlooks the ubiquity of conspiracy and gives supremacy to particular touchpoints of an experience that is so pervasive in Western culture. Conspiracy results from a relationship to power, and the impulse to create a reality that allows an explanation for things we cannot, or refuse, to accept, causing art to have particularly strong faculty in the process of engaging these shifts in reality.

Sue Williams “Hill and Dale, Black-Ops” (2013), left. Oil and acrylic on canvas.

Sue Williams “Mike and Zbigniew” (2012), right. Oil and acrylic on canvas.

Close-up of “Mike and Zbigniew.”

The power of Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy does not lie in its perfect position within our current moment of political turmoil, but in the anxieties it conveys through its own shortcomings, revealing a greater statement to the limits of control during a time of paranoia. The pieces of this exhibition represent a reality that is alluring and ungraspable, creating an cycle of thinking you know more than you do. Everything is Connected begins and ends with Wayne Gonzalez’s massive “Peach Oswald” and “Dallas Police 36398,” monochrome portraits of the presidential assassin and the man who shot the shooter, side by side. They are both intimidating and inquisitive, and the hypnotizing connectivity of these works make it easy to round the corner and start the route again, continuing the swirl.

Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy can be seen at the MET Breuer until January 6th, 2019.