From the Archives: Abelardo Morell

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura, Afternoon Light On The Pacific Ocean, Brookings, Oregon, July 13th, 2009 ©Abelardo Morell

This interview originally appeared in Musée Magazine Issue 15: Place

Andrea Blanch: You were fourteen when you left Cuba. I’m curious to know how your Cuban background influences your work?

Abelardo Morell: Where were you born?

AB: Brooklyn.

AM: How does your Brooklyn background influence your work?

AB: Well, I have a tendency to like cities [both laugh].

AM: I think the biggest effect it had on my life was the idea of leaving a place that I had been born in, and arriving in NYC at 13 or 14. That shift, the relocation...not necessarily being Cuban, but just the relocation. The exile experience that so much of America is like, that was a realreset for me. The Cuban thing, you know, not sure that I could specifically say what about Cuba or Cuban-ness has affected me, but I think growing up by the beach and the sea was very important. I grew up right by a small beach town, and I think that sense of openness and infinity did give me some sense of ambition.

AB: I’ve never met a Cuban that doesn’t work hard. I have a Cuban friend and I call him the Cuban Missile, and you’re very prolific. It may be a generalization, but from what I’m hearing from you I think it’s true.

AM: I think probably exiles tend to generally work harder because there is a certain thing that they’re maybe trying to compensate for. I didn’t speak English when I arrived so in some ways I was trying to compensate for deficiency early on. And also as a way to prove to Americans that, you know, I’m as good as you guys. I thinkwe are constantly trying to prove ourselves.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura, View Of The Brooklyn Bridge In Bedroom, 2009 ©Abelardo Morell

AB: I have to say to you, I think your work is sublime. I’m curious, how did you get to camera obscura and using that process for your work?

AM: I was teaching at a college in Boston called the Massachusetts College of Art, and in 1991 I had a sabbatical for eight months. I had been working on optical pictures; pictures of light bulbs and things like that. Just crude objects being examined by my work, my glasses and things like that. Then I thought of how in the mid-80’s one of my teaching methods was to turn my classrooms at Massachusetts into camera obscuras. I was really affected by these savvy kids all kind of going, “Oh my God!” You know, they were really touched, so I knew there was something really powerful about that phenomenon. So in ’91 I thought, why not try to make a picture of that effect, the phenomenon itself, which had not really been made before. People have used pinhole cameras, but a photograph inside a room converted into a camera obscura and photographed, no one had done that before for some reason. It was always mentioned in art history texts and things like that, so in ‘91 I attempted to try and make a picture like that, and when it came out I was just kind of blown away by how wonderful and weird and crazy it was. But it did take me a while to get the technical stuff going on. Those exposures back then were made with lm and just a pinhole—well, not a pinhole but a 3/8ths of an inch hole—and those exposurestended to be about 8 hours long, so it was a strange beginning. It was like the beginning of photography in some ways for me. Now of course, things have changed radi-cally, but that was the beginning. In some sense, I’ve tried to achieve surrealism through very straight methods. Notby putting oating elephants in the room and shit like that.

AB: What’s the process like now? You say it’s changed radically, so how has it changed?

AM: So the beginning pictures from ’91 were just basically me darkening the whole room with dark plastic and then I would make a small hole, like 3/8ths of an inch looking out. So, a very dim image of the outside showed on the opposite wall. It wasn’t super bright, so those lm pictures just took a lot of exposure to get themright. Some of them, like I said, were 8 hours long. Overtime I’ve developed ways to get the image brighter by getting a lens made that will focus on the distance of that wall, not only brighter, but sharper. Then I found ways to invert the image so instead of them being always upside-down, I can turn them right side up. I’ve shot in color, and recently—well the last 5 or 6 years—I’ve been using a digital camera. So the 5-8 hour exposures are now 3-5 minutes long. So it’s changed radically.

AB: I have to tell you, the whole thing just doesn’t make sense to me, and I’m a photographer! So I don’t understand how you use a digital camera for your method; I don’t get it!

AM: Well my digital camera is just like a film camera, except it’s got a digital back. And what happens with digital technology is that film has something called reciprocity, which means that when the light is low level, film doesn’t react to light in a regular way. It just takes a lot longer for it to receive these photons of energy. So, if your meter says 2 minutes, it’s more like 2 hours. Digital technology doesn’t have any of that reciprocity—just, what it is, is what it is. It tends to get it a lot faster. The nice thing about that is that now, in my pictures, I canget clouds, I can even get people to show up. So there’s a certain momentary feeling of time, and I think that’s really helped a lot.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura, View Of Central Park Looking North – Spring, 2010 ©Abelardo Morell

AB: Yeah, and you can do much more!

AM: I know! Before, I would start an exposure at eight in the morning, I would go uptown, see my dealer, see a movie, go to the Met, have lunch, and then come back and hopefully then not only come back to New York, but then take the train to Boston that evening, get home, develop the sheet of film and see if I even had anything. The process was very primitive.

AB: Do you think you’re going to stay with this method?

AM: I’ve been developing it more so I think they’re very different pictures that I’m making now. So yeah, I’ve been making different kinds of pictures enough to want to stay with it. I’ve also been using the Tent camera, I don’t know if you’ve seen that?

AB: The what camera?

AM: The tent camera

AB: Oh yes, I was gonna ask you questions about that.

AM: The tent camera is sort of an outgrowth of the camera obscura technique. I had a commission to do work in West Texas a couple of years ago and they were wondering if I could do camera obscura pictures in the desert, and I pointed out that there are no rooms in the desert, so no, I can’t doit. So I thought about making a portable room in the form of a tent. And I continued to make work in that way too.

AB: Would you say that texture is important to your work?

AM: Yeah, well, for instance, in the ground pictures texture is very important, because if I get a landscape of a thing falling onto the ground, the different patinas and textures of the ground change the nature of image, so it’s like a painting or something, it provides—texture is part of the meaning of an image. So yes, very much.

AB: You describe much of your camera obscura work as “painterly,” aside from Monet, your project “After Monet”, which other painters have influenced you?

AM: Well, I’m a closet painter. I don’t know howto paint, but I love looking at painting. And of course, photography grew out of painting, so you name it. The current project that I’d like to talk to you about is Monet, but when I was a teenager in New York City, I went to MOMA a lot, and then I loved the surrealists, the Magritte and the Kiro and people like that. But then Picasso and all those modernists became very important to me and to this day my studio is mostly full of art books, which I constantly look at, and I’m constantly trying to and some avenue to combine some of my painterliness into my work.

AB: Well you’ve succeeded.

AM: Thank you.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura, The Philadelphia Museum Of Art East Entrance In Gallery #171 With A Decherico Painting, 2005 ©Abelardo Morell

AB: Your work is the intersection of different worlds whether it is indoors and outdoors in the case of your camera obscura series or two-dimensional or three- dimensional with your Alice in Wonderland series. What about exploring the intersections of seemingly separate worlds appeals to you?

AM: That’s a good question. Maybe a little bit it goes back to that issue of being a young immigrant in NewYork in the sense of it being that I was de nitely not in that world, I de nitely felt separate you know. I don’t mean in a discrimination kind of way but just that that world was not mine. And that sense of breaching or getting to know this other side has been with me a lot; that sense of overcoming the distance. I think in some ways the New York pictures—the camera obscura pictures—are very much about a man, a young man, who was overwhelmed by a city. Andnow in some ways, I’m making more private New York City pictures. In some ways, understanding what I didn’tunderstand before.

AB: Although your works are all combined elements of reality, are you at all in uenced by fantasy?

AM: I don’t think so. No, I’m more in tune with“the real” being quite complicated. The way that magical realism and Latin American literature suggested that real is quite crazy. The fantasy part can lead to a kind of wishy-washy softness that I’m not interested in. I mean, I like Magritte very much because his paintings are of very normal things—a door, a chair, an apple. So the reality of that is really interesting and when you make something that com- mon strange, I think it feels more earned as an artist than just making up unicorns.

AB: Which thoughts or emotions do you hope to provoke in your viewers when they look at your work? Do you consider that?

ABELARDO: Well of course. I always have an audiencein mind. I’m not a mad person who doesn’t know what they’re doing [laughs]. I’m not a primitive artist in that sense. I do have trouble with the fact that I’m showing them something that they’ve seen before, but through a different mirror, a different conduit. I like surprising people with what they know, but seen in a different light. To me that’s the most fun.

AB: How does the arduous process of setting up for a shot add to the experience of the image?

AM: I think it’s important. I come from a working class background, so in order to get anything done you had to work really hard. That’s part of my philosophy. My father and mother worked extremely hard when we moved to New York. I think taking time to make something, I think the worldor something pays back. There’s a certain feeling of earningit which I love. Though it may not be in the picture, or the fact that we just came back from France and we worked really hard, but for one picture we were in the tent for like four hourswaiting for the right light. And it matters. It’s like, “no, that’s good,” ”nah,” “no, another half an hour?” Getting it right is really important I think for me, but it is also good art, I think ifsomeone has gone the extra length to get something well-said.

AB: And I would think that people would know that either doing camera obscura or using those techniques, you’ve earned it [laughs]! It’s a statement about that.

AM: Someone I was living in Texas with once said something like, “Why do you work so hard? Why don’t you just project whatever the hell you want on a slide projector in a room and just do the Taj Mahal and New York or something?” And I was like, “That would be fucking boring!” While everything like that is possible, it gets really uninteresting. Part of being tied up with reality andthe way that it does things is that there’s an engagement.That I think makes me even think differently. So you needto do that. You can’t just sit in your pajamas and just makewhatever you want in Photoshop.

AB: Many photographers say that the benefit of photography is its quickness, and with that it allows for more happy accidents. Do you ever have accidents?

AM: Basically with whatever in my pictures I see exactly what’s happening. But yes, accidents happen all the time. When I make a two-minute exposure, I don’t know that the man is going to stand for two minutes on the side-walk and show up. I don’t know that the light will change and give something a glittering look or something. Now it feels like I’m—because of the ground and the unruliness of the ground in my tent pictures—definitely welcoming chaos and chance and randomness a lot more than I’m used to. Maybe it’s my old age or something.

AB: Yeah you’re very old [laughs]. You describe photography as a language and as your preferred lan- guage. How do images for you succeed where words fail?

AM: Well images and words are such different animals. But I think paint it right or I think photograph itright. Sometimes, I would even say it’s better than the realthing, because it solves a certain problem of being that it is separate from real life. When you see a painting that showsan emotion or moment, like a sunset pic...er not a sunset, but there’s a certain intelligence that art brings to life that when it’s right it shows the moment at its best.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura, Garden with Olive Tree Inside Room with Plants, Italy, 2009 ©Abelardo Morell

AB: So you use, not all the time, but you use water, salt, natural elements in your work. How does the natural and unnatural play off of each other in your photograms?

AM: Oh, the photograms. I mean I like the idea of basic things like salt and water – like the alchemic sense of making something magical out of crude elements – so lately I’ve been making pictures of flowers. I don’t know if you’ve seen those.

AB: Yes, I have.

AM: And I’ve been also making cliché verres. Do you know what those are?

AB: No.

AM: In the 1850’s a number of French artists – French painters, namely Coureau and Melé – had this interesting idea where you take a piece of glass, you know any size, but 8’’10 say. They would cover it with soot froma candle or something, blacken the plate, and then with a drawing tool they would make drawings on this blackened glass plate. So they could draw, and make, whatever, a tree and a person. But, this is the interesting part: what they did was they exposed that plate with a piece of photographic paper, so like a contact print. What came out of that experimentis a drawing on photographic paper. So they called it glassimages, cliché verres. And I love these pictures so much thatI embarked on making some for a project I made for the Museum of Modern Art [MoMa] with Oliver Sacks trying to get drawings of ferns and cycads things that Oliver was really interested in – and I made a bunch of cliché verres related to that. And lately, for this ower project that I’m calling Flowers for Lisa and the Monet project, I’m trying to work on cliché verres involving owers, pressing owers on color ink,things like that. And then what I do is that I scan those plates and I make a print out of it.

AB: I only saw one image of that, the flowers, just recently actually.

AM: The crazy owers?

AB: If I remember correctly, they looked like they were in a vase on a table but they were like a big...

AM: ...explosion.

AB: Yeah.

AM: That comes from a project called “Flowers for Lisa”. So I’ve been trying to photograph owers in all kinds of ways. I’ve got two pictures like that where there are multi-ple exposures; there are about 20 exposures of bouquets in a vase, so essentially just double exposures times twenty. And then when you do that in Photoshop it’s kind of like a chaoticblend of accidents and plant stuff and all that. Anyway, now I have about 20 pictures called Flowers for Lisa. Not just using that technique but all kinds of techniques.

AB: What are you photographing with? Camera obscura in the tent?

AM: No, no. With a regular...

AB: A regular camera?!

AM: No, my digital camera, but in my studio. Iput a vase, put two or three owers in the vase, and pho-tograph that. Then I move the vase, take those owers out,put another set, and do that several times. And at the end I put them together in some crazy way.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura, View of Valle De Viñales, Pinar Del Rio, Cuba, 2014 ©Abelardo Morell

AB: What about the Monet project? What is that about?

AM: For the Monet project I spent time in Givernywhere Monet’s gardens are. Last year I was in residence fora bid there so I brought my tent camera to the gardens and I made five pictures that I love, love, love. So I thought, “Okay. There’s a project here. I’m going to call it, After Monet and it’s to go to some places in Normandy where he painted and I’mgoing to use the camera obscura, the tent camera, and other things having to do with his paintings or the way he worked and all that. So I just came back, like a week ago, and I went to Girverny again for the garden pictures, I went to Ruan where he made the cathedral paintings – I made pictures there – I made pictures in Étretat, a coast town, and they’re amazing. It’s an incredible project. I’m very excited.

AB: Has anybody seen those?

AM: No, no, no one.

AM: Well, can we use some of those?

AM: Well here’s the thing, I’m trying to get the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston – you know they own a lot of Monets – to...let me think about it. They’re really special. So this, after my project we’ll also include some when I’m pulling Flowers for Lisa because they’re related to a kind of Monet attitude. And I even got some camera obscuras from Paris that are amazing that I think in some ways have this Monet feeling to them. So, I can send you some stuff.

AB: Yeah well if you can just remember that the theme of this issue is place [Both laugh]. Just putting it out there.

AM: Okay. I got it.

AB: Okay? And God I wish you were in New York I’d love to meet you. Why’d you choose Boston? Is that where you teach?

AM: I used to teach there. I retired 6 years ago. I still teach a graduate class in the fall. Yeah I mean I got a job teaching at Mass College of Art in ’83. So I taught for 30 years. But I like Boston. It’s kind of slightly boring which is nice. It’s not like your city. So um...it’s so aggressive.

AB: [laughs] Everyone but me.

AM: Yeah you’re so nice. You don’t sound like you’re from New York.

AB: I would just like to know, this is a boring question, but... You are a large advocate for older, more hands-on methods of image creation. How do you see that... what kind of an effect do you see that having on photography in the future?

AM: You mean, digital technology, or...?

AB: Just where it’s going, you know, because everybody uses their iPhones, the technology now is like...There’s a lot of people in school who are going back to analog photography, but I would say that most people use digital.

AM: Yeah, no, I agree. Many artists, including myself, have gone back to older ways of devising pictures and it’s a way to reset the original love for it, and I think that’s part of it. Students now love film because in a way it’s sort of like... this digital is a little bit of this bullshit iPhone thing. So I think they want to have a little bit more heftiness in their work. Although I agree, I do think that digital technology is just another step in the process of image making and it’s what’s working and what I love about it. I’m trying to make new pictures using... like the way those ower pic-tures were, giving Photoshop 20 exposures and trying to let it decide how it’s going to arrange it. It’s part of this interest- ing battle between your intentions and what digital stuff is.

AB: Yeah. Maybe I should go back to using lm.Maybe I’ll get more interested again. Seriously. The magic is gone. I grew up with lm cameras and I haveto say I use digital but I thought the magic was taken away for me.

AM: Well I think it can. Yeah it can. And that’s why I’m inside some tent in France during a hailstorm, waiting for it to pass so I can make a picture. I’m trying to get myself the irritation of the old so I can make new pictures.

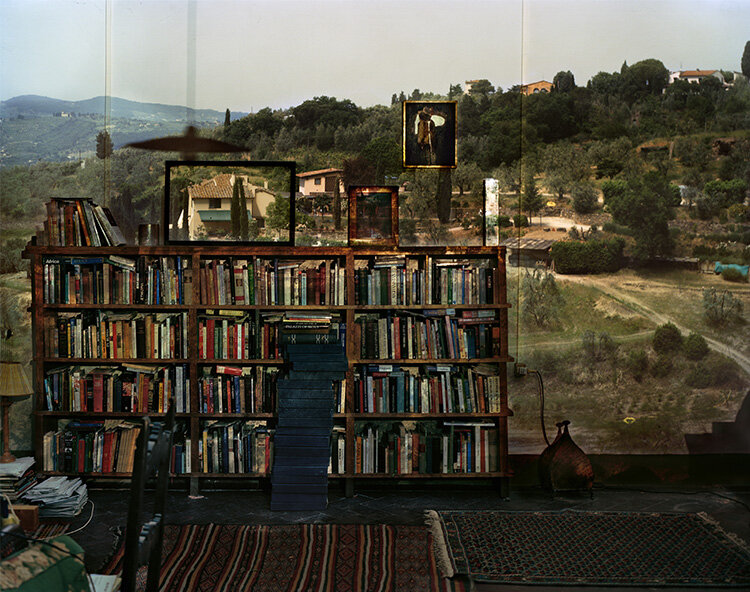

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura, View Outside Florence With Bookcase, Italy, 2009 ©Abelardo Morell

You can view more of Abelardo Morell’s work here