James Welling: Back to Now

Artist portrait, 2019.

Lingfei Ren: Your newest series Personas are reanimated images of Roman and Greek busts. You have started to photograph Roman sculptures since Julia Mamaea (2018). In that series are more than 30 prints developed by different printing processes with the same negative of Julia Mamaea, mother of Emperor Severus Alexander. What intrigued you to start with this subject matter?

James Welling: I had been photographing dance from 2014, a project called Choreograph, and I decided I wanted to work with sculptures. I saw an exhibition that linked the origin of modern dance, at least with figures like Isadora Duncan and even Martha Graham in the early part of the 20th century, with antiquity, specifically Greek culture. So it seemed like a natural segue to go from modern dance, with its interest in classical themes, to photographing classical sculpture. The show I saw was a show that compared modern dance imagery from the early part of the 20th century and its reliance on antiquity. It was at NYU, a show that was called the something of Apollo. I can get you the title. So I went to the Met and began to photograph all kinds of sculptures, not just Greek and Roman. When I came back to my studio, I looked at the images and discovered that one picture stood out, a photograph of the bust of Julia Mamaea. I didn't know who Julia Mamaea was, but she had a name, unlike a lot of these sculptures. I researched her, discovered who she was. The mother of an emperor, but also the effective ruler for 10 years of Rome while her son came of age. What struck me about the sculpture, of course, was her eyes. Her eyes were carved, as they were in many sculptures from that period, but these eyes were not only carved, but they were alive. And every time I printed the picture, I started printing as gelatin silver prints and then I began to make inkjet prints, the eyes were very haunting. Because I was also experimenting with an experimental process, handmade emulsions, I began to print Julia Mamaea with a handmade emulsion that I created with gelatin and potassium dichromate, to which I added dye. So all of the pictures are made with dyes. So they're color photographs, one and two color photographs, of this sculpture. Each time I printed it, her face seemed to change. She became a contemporary woman. Next picture, she'd look like a Roman woman, then an English woman from the 19th century. She also transformed into a man. So there were gender changes and historic changes in the face every time I printed it, which was an experience I'd never had with photography.

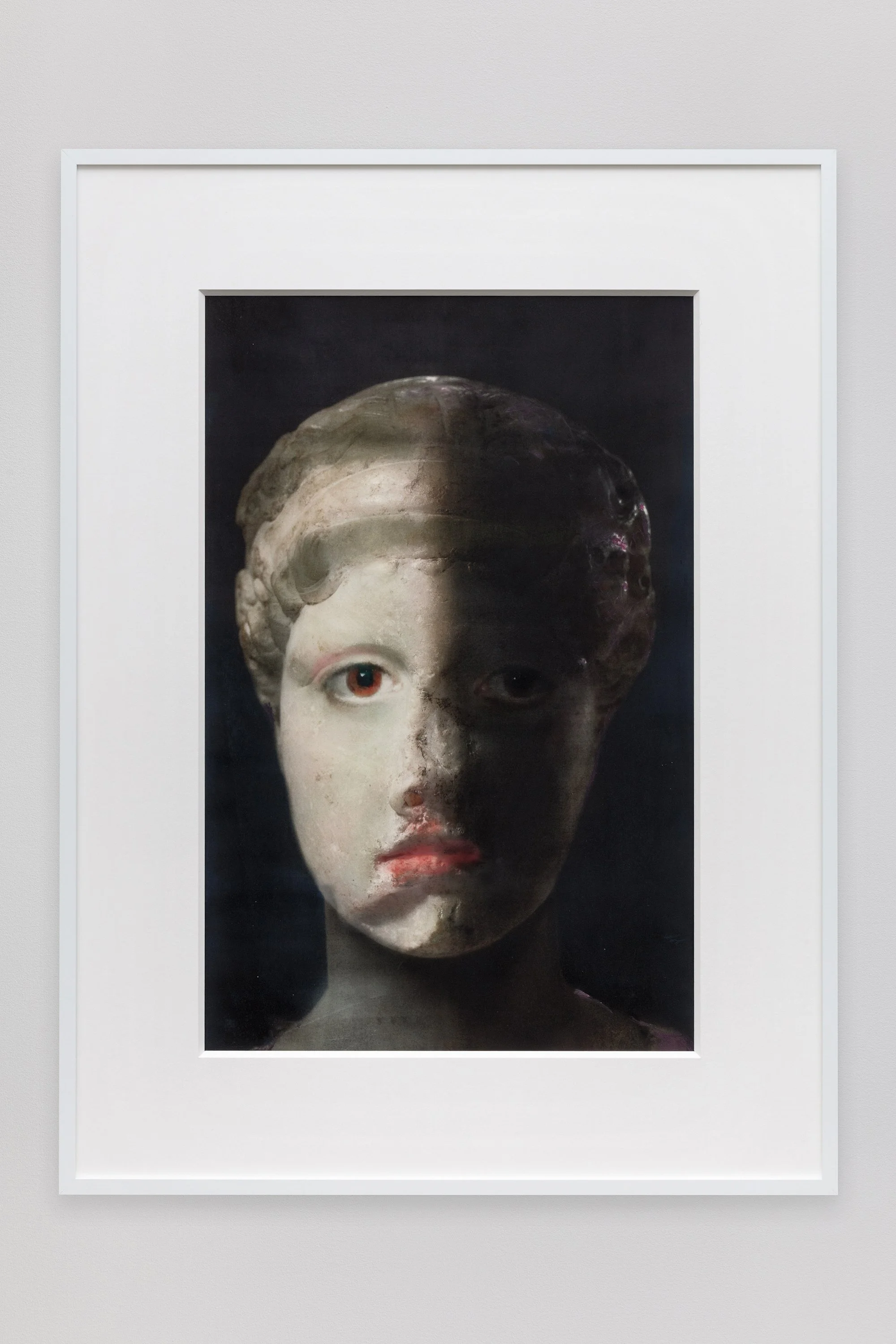

James Welling, Portrait of Aphrodite, 2022

Lingfei: You once said you always thought that there was a relationship between photography and cooking that you wore an apron, you had got different procedures, and you were with lots of water. When you were making those prints of Julia Mamaea, were you playing with various chemical recipes to get different “flavors” of imagery of this particular figure? Are you allowing yourself to be out of control of the results?

James: Yes. Well, working with alternative processes that they're called in photography is an invitation to disaster, that a lot of times what you are interested in making doesn't follow. I was reading a lot of old photography recipe books, as it were, how to make these older processes, which is a lot like reading a cookbook. And some people like to read cookbooks as literature and I certainly loved reading old photography source books and chemistry books as a form of literature. I'm not going to make a lot of the processes, but I'm fascinated by the wonderful experimental inspiration that these pioneers of photography created in these different books on how to make 19th century style photographs. People have compared what I do to steam punk, kind of going back to older forms, but with the kind of punk attitude. I don't really think of myself as a steam punk person, but there is a certain kind of appropriateness to calling this process steam punk.

Lingfei: In 2010, MoMA had a show called The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today. It was an examination of the intersection between photography and sculpture by artists using photography as means to record, analyze, and question sculpture and reinvent images from it. Speaking to your work, specifically Cento and Personas, were you thinking of any relation between the two mediums?

James: Well, I did not see the show, but I bought the catalog. I previously had been photographing a wide range of sculpture. It was a project that I called Form, F-O-R-M, but most of the sculptures were contemporary sculptures like Charlie Ray or Michael Asher or Tony Smith. It's a project that I've never exhibited. So I was already thinking about sculpture when that show came out. To go into the museum and photograph, of course, it makes a certain kind of statement that I wanted to photograph museum objects rather than on this street, for instance. I found it more to my temperament to photograph sculpture in museums than to, say, do street photography.

James Welling, Niobe, Everlasting Sorrow, 2020

Lingfei: There is a quote in your exhibition at Regen Projects: “At a symposium in 1949, the question arose, ‘Where do we go from here?’ Paul Strand’s terse rely was, ‘Go to the Metropolitan Museum.’” How do we interpret it?

James: Yes. So I wanted to make it very clear that I was following Paul Strand's advice, two years before I was born. He's speaking from the grave, as it were. But to be serious, Strand was basically saying that in order to make art in troubled times, it can sometimes help to look at earlier subjects of the "masters" or of historical work we have collected in this thing called a museum. For instance, Paul Strand was very interested in the work of Piero della Francesca, which he must have seen both in Europe, but also in the Frick, and similar examples at the Met. So I think this advice was something that I thought was good, especially during the Trump era and also during the COVID period, that to look at art that had been made in other troubled times and to try to draw some ideas from that. It was really a reaction to Trump.

Lingfei: It is good advice, and that’s why museums collect and preserve historical things so that we can look back at history. Also, for the history of photography, it is easy nowadays for us to forget that the actual craft of photograph printing is a complex and physical one, since a major number of photographs are viewed as digital formats on the internet. In Personas and Cento, you’ve done both digital and physical work on the prints. Could you explain more on the process of making?

James Welling, Julia Mamaea, 2018

James: Yes. So Cento and Personas use a non-toxic form of printmaking. Julia Mamaea was made with carcinogens that I decided I didn't want to continue using. So I researched non-toxic printmaking and discovered that a laser printer could be used to produce a kind of lithographic plate. It was a long process of how I went from making printing plates to actually showing the plates, but at a certain point, I thought that the plates were more interesting than the prints I was making. So Personae and Cento are plastic lithographic plates that I cover with oil paint. However, in both those series, most of the color in the picture is done on the computer. Then I printed out with a laser printer onto a special piece of plastic that I then apply a very thin coat of oil paint, which gives it a sort of texture and dimension that the laser print doesn't have. Also, the plate I'm printing on is translucent, so there's a little bit of light bouncing back through the picture, so they almost glow. That also changes how we experience them. So there's not a lot of paint on the surface of the prints. There is a confusion because I do apply color with the rag and with a roller and also with what are known as oil pastels. So there's a physical quality to each picture.

Lingfei: That’s really cool, giving a contemporary approach to the ancient sculpture as to look back at history, your works contain time, memory, and inherited tradition of aesthetics and iconology with development of techniques and innovation.

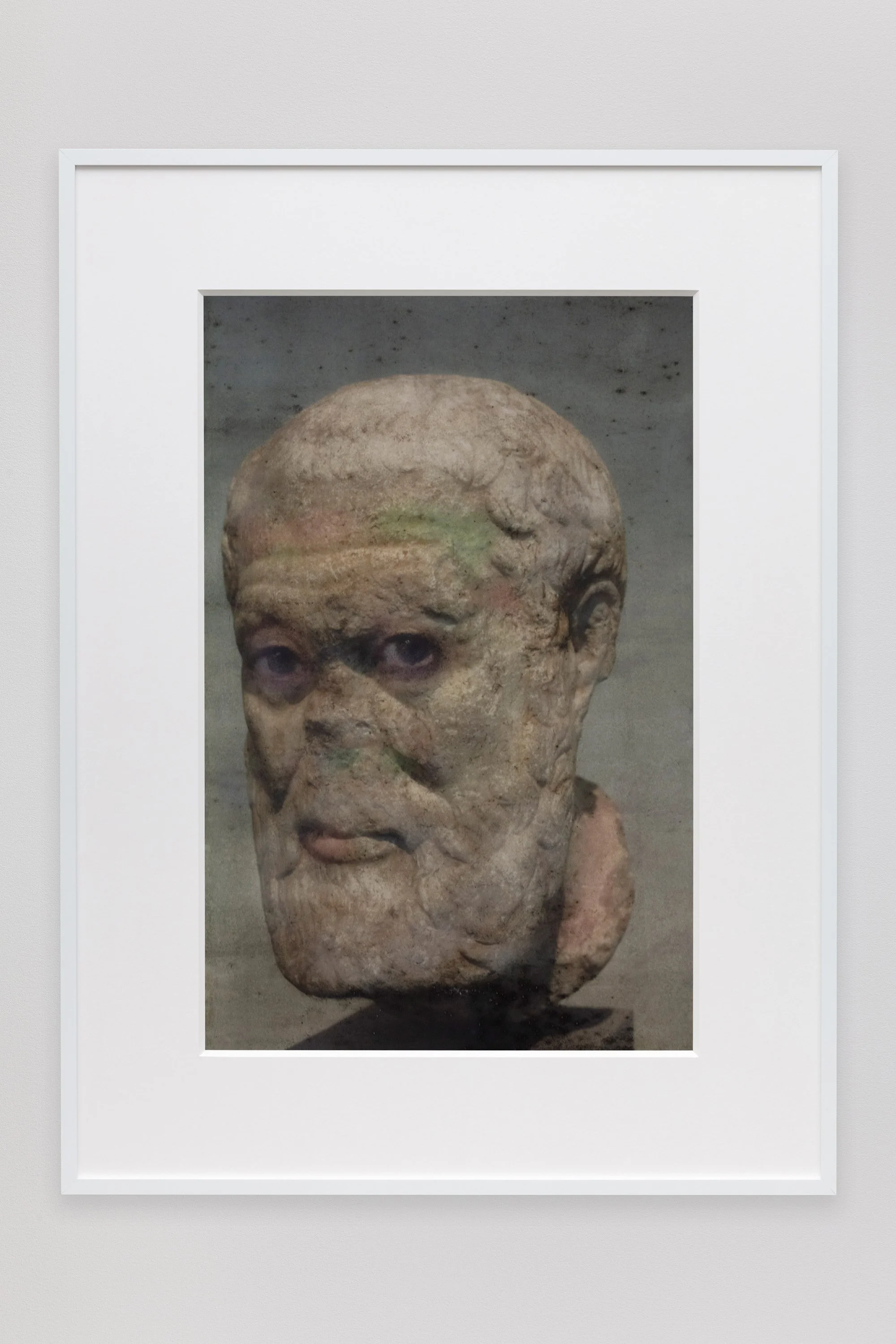

My use of photography was as a conceptualist, not as a practitioner

James: One of the things that I've always thought about photography is it's a form of time travel. When I first started making photographs, I photographed a 19th century diary and old handwriting. I was struck by the fact that these photographs I was making looked like they could have been made in the 19th century. So time travel, the idea that the medium of photography is a time travel medium, was something that I continue in these two bodies of work. My feeling is that I'm not a scholar of Antiquity. I'm not trying to do make some sort of special point about say, even polychromy, the way ancient sculptures were painted. We all know that they had color. I'm not trying to reproduce that color. I'm trying to bring the past into the present with whatever tools that I have. I'm not an archeologist. My attachment to these sculptures is more emotional, that I can bring these faces into the living present and so that's the ambition, to reanimate these faces and bring them alive because these people were once alive. So it's a sort of homage, perhaps, to the lives that they lived. But of course, I'm making new personalities at the same time. These are not the faces, the eyes that were in these sculptures, I'm borrowing eyes from a lot of different paintings.

Lingfei: Yes, I’m very interested in the eyes. It is always the crucial part of a work and where a work started with. In Personas, The images of the eyes that replace those of the sculptures are appropriated from paintings rather than photographs, what is your consideration in terms of representation?

James: So there's an exhibition right now at the Metropolitan Museum called Chroma, and it recreates the colorful appearance of Greek and Roman sculptures. A number of art historians have been trying to recreate what those sculptures look like and they have painted eyes. Sometimes, Greek and Roman sculptures have precious stones, crystals in their eyes. The idea of polychrome is all of these sculptures from antiquity and many different cultures, Egyptian, I know about Egyptian and I also know about the medieval, they're all polychrome, they're all painted sculptures. But because the Greek and Roman material was buried or weathered for 2,000 years, all the colors disappeared. Of course, they've also been cleaned up by overzealous merchants who wanted to sell these white sculptures to white Europeans. Whereas you go into any church in Europe and you see polychromed biblical figures, it's just that antiquity Europeans prefer white. Anyway, all of that stuff is in the background. I know all of that, but I began to look at some of the ancient, they're called Kore sculptures, which half their eyes are still there. And many of these sculptures were discovered only 140 years ago, buried underground. So when they were brought up, they still had their polychrome on them. I was using one of the Kore sculptures and I was trying to hand paint the eyes and that wasn't very successful. I began then to Google eyes and I found lots of different digital eyes. Those looked too freaky. They just didn't look right. Then I was on the internet getting my email one day and it was Édouard Manet's birthday. All the museums who had Manet paintings were posting their Manets. So I saw that the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has a Manet painting, and I could go and photograph it, which I did. I took the eyes and put them into this sculpture and it just completely came alive. So I realized that photographic eyes didn't work. But only they would come alive in a way that interested me if they were painted. So I began to go to museums...So I have what I call an eye bank. I have a large eye bank now of all kinds of eyes. I do corneal transplants. So recently, someone wrote a review asking why I didn't put noses and mouths into the sculptures. Well, they have noses and mouths, but they don't have eyes. So the eyes became so important in terms of giving them personality and ethnicity, depending on how I treated the eyes and also the hair. Right after the eyes, I became very interested in hair and makeup. Which I don't do a lot with makeup. I just try to give a skin a vibrancy. The hair color is also an option. So hair and eyes are the two things that really transform these sculptures into presences.

James Welling, Portrait of Hypereids, 2021

Lingfei: It's really fascinating how different medias are mixed in your work. You are combining painting, sculpture, photography, printmaking, and digital manipulation altogether. How do you balance or amplify the characteristics of each medium, and how do you control the tensions between different representations?

James: So when I'm working with the Personae, the angle that I photograph the sculpture is very important and I realize that I'm taking a photographic approach. I want the image that I make to be a portrait of the sculpture. This means sometimes photographing at an angle, sometimes moving in very close. Even though I do use internet images too, I try to transform them in some way. At a certain point, I realized I was not going to make it, I was not going to go to certain museums. So I used images from the internet. I'd say 10% are internet, 90% I photographed. But even with the internet pictures, I crop them, I change them, I flip them around. The photographic part is very important, that's the foundation in the museum making the photograph. So I'm dealing with photography and sculpture there. Then the digital transformation is pretty much creating a background, taken out of the museum, putting it somewhere else, which is just generally a dark or a monochrome field. I also have to create the skin tone, which I've discovered you just can't put a monochromatic tonality of whatever color of skin you want. Human skin is composed of red, green, blue, orange, and purple tones. So I have to go in and different layers of transparency using different brushes and as I paint in the skin tone, this sort of rainbow of human skin, then I have to choose the type of oil paint that I'm going to use. Sometimes, it's just straight oil paint. Generally Mars black and Prussian blue, bluish black. I also mix in what's known as transparent base. It makes the black more transparent. So I'll have a very transparent, almost negligible color, but it will still have an oil surface to the print, which then I can put powdered pigments. I have a sugar shaker and I shake pigment into the oil paint or I use oil stick where I draw on it. So the oil paint, we have the digital manipulation of the file, mostly skin tone and background, and then the application of very subtle different oil paints and then using crayon or powdered pigment or abrasives like toothpaste where I remove too much paint. I scrub away with toothpaste, which is something that's used in lithography. And then finally, I sometimes put wax on the print to actually cover all of the surface marks that I make, which sometimes are distracting. So I wax the print, which are all of the steps that I go through, but it really starts with the original photograph. To me, if the sculpture isn't in some way alive in the photograph, then it's not going to work in the final print.

James Welling, Hands, 2020

Lingfei: When you were studying at Cal Arts, what was the main medium you were using?

James: Photography and video. But my use of photography was as a conceptualist, not as a practitioner. So I would have other people print my photographs or I'd use a photographic lab. I wasn't in the dark room as a student. But one of the things that's not so well known is I have made portraits. When I was just starting to learn how to use a camera, when I was 25, I made portraits of my friends. So I don't know how, if you're going to reproduce those in this article, but I do have some portraits that I really thought of as busts, as posed pictures from the chest up of people looking off to the side. So to me, there's a connection, a 50 year connection between my earliest photographs, which were of people, friends, et cetera. And these more recent things. I also photograph... I have a photograph of Wolfgang Tillmans and my light sources book and other friends. That was around 2000, I did a very expansive body of work that also included occasional portraits.

Lingfei: Yes, and they're mostly in black and white, right?

James: Yes.

James Welling, Julia Mamaea, 2018

Lingfei: I see you began to focus on color with the Flowers series (2004-17), and especially in Choreograph (2014-20), colors are intensely tinted and contrastively mixed. But from Cento to Personas, you start to reduce the saturation of color, giving them a more matte and earthier outcome, and the images are more contemplative thoughtful and self-reflective. Was Pandemic part of the reason or what led to this transition?

James: Yes. I don't want to emphasize that they're pandemic works as I began them before the pandemic, but when the pandemic hit, I had everything I needed to work in my studio. I didn't have to go to a lab. Whereas Choreograph was printed outside. In some earlier UV prints I was using a lab. The color photograms of Flowers also used a lab. So for sure, I was excited about being able to work, continue this project with my inventory of images that I already had created of source photographs. So Cento was really a pandemic project. By the time I got to Personae, I was going to museums again. But my whole exploration of color of which Cento and Personae are still in this move that I made, I started in the early 2000s with Flowers, looking at color as a phenomena, not just part of the subject, but as a technology. Every one of these projects from Flowers to Choreograph to Julia Mamaea, Cento and Personae, and also I made a film called Seascape, that's hand colored digitally, all of those projects are taking color as part of the equation and not as a given. And I'm working with color specifically.

Lingfei: Art students always have classes about the theory of color and learn how to create the harmony of color. But in your work, sometimes, the use of colors is not at all following the so-called harmony of color. What is your take?

One of the things that I've always thought about photography is it's a form of time travel

James: Well, with Choreograph, I was really interested in psychedelia, psychedelic color, and I was interested in artists, other photographers and other artists who worked with psychedelia from the 1960s onward. So it was an homage to the colors of my adolescence. When I was growing up in the '60s you would see these very bright, vibrant colors. I really wanted to learn about the techniques of how psychedelia was created in the '60s and, to use some of those same techniques digitally. So there was a digital modeling in Choreograph. In Seascape, a black and white film that my grandfather shot in 1930, I worked with a team of animators and then I also did a lot of color work on the film to take a black and white image and turn it into a color image. That process helped me with Personae to create skin tones because I realized you have to have lots of different colors. And so colorizing the black and white film was helpful. Also just thinking a lot about how we see color rather than color harmony. Color harmony is important and it's the basis for a lot of painting and decor and personal apparel. But I also wanted to work with the phenomena of how our eyes see color, how personal it is. Turns out we all see the same colors with normal color vision, but how we process them is different. So our hardware is similar unless you have colorblindness, but then the part in the back of the brain of how that works is the fascinating part about color. I teach a class at UCLA and now at Princeton on color called Pathological Color. It really deals with psychedelia and also just color perception. Pathological meaning sick color, diseased color.

Lingfei: You mentioned about your teaching at UCLA and Princeton University. School is an important part of the construction of art history. For photography, there are so many directions to go. As a teacher or as the head of photography at the school, how do you influence your students in regards to the direction?

James: When I started at UCLA, there had been no one running photography for a few years. After I started teaching or running the photo program someone said that, "Jim, the photography labs are now a happy place." I couldn't imagine a better description of what I want photography to be. I want it to be a happy medium that is excitement over what photography is and what it can produce. So I'm very open-minded about what people I want to work with. I mean, I could teach an all digital class, and my ideal teaching is also to show how digital comes out of analog. And the analog, it's basically history. I love the history of different mediums.You can do it in painting or sculpture, ceramics, all of the technologies around art making. Even the newest digital is tied to what came before and how it emerged. So even when you're using digital, if you only shoot digital and don't use film, you are still using the template or the model of film. The way we think digitally is based on earlier forms. So my teaching style is I just try to be open minded. Of course, I'll tell people not to do things, but I only would do that because it's too hard. Not because it's not viable. Yes, if you want to do something, if you wanted to work in film, it's hard and sometimes, in a 10 week class, it doesn't make sense, but if you've got 10 years, yes, you can work in film.