Michael Stipe: A Lyrical Vision

Portrait by David Belisle, 2023

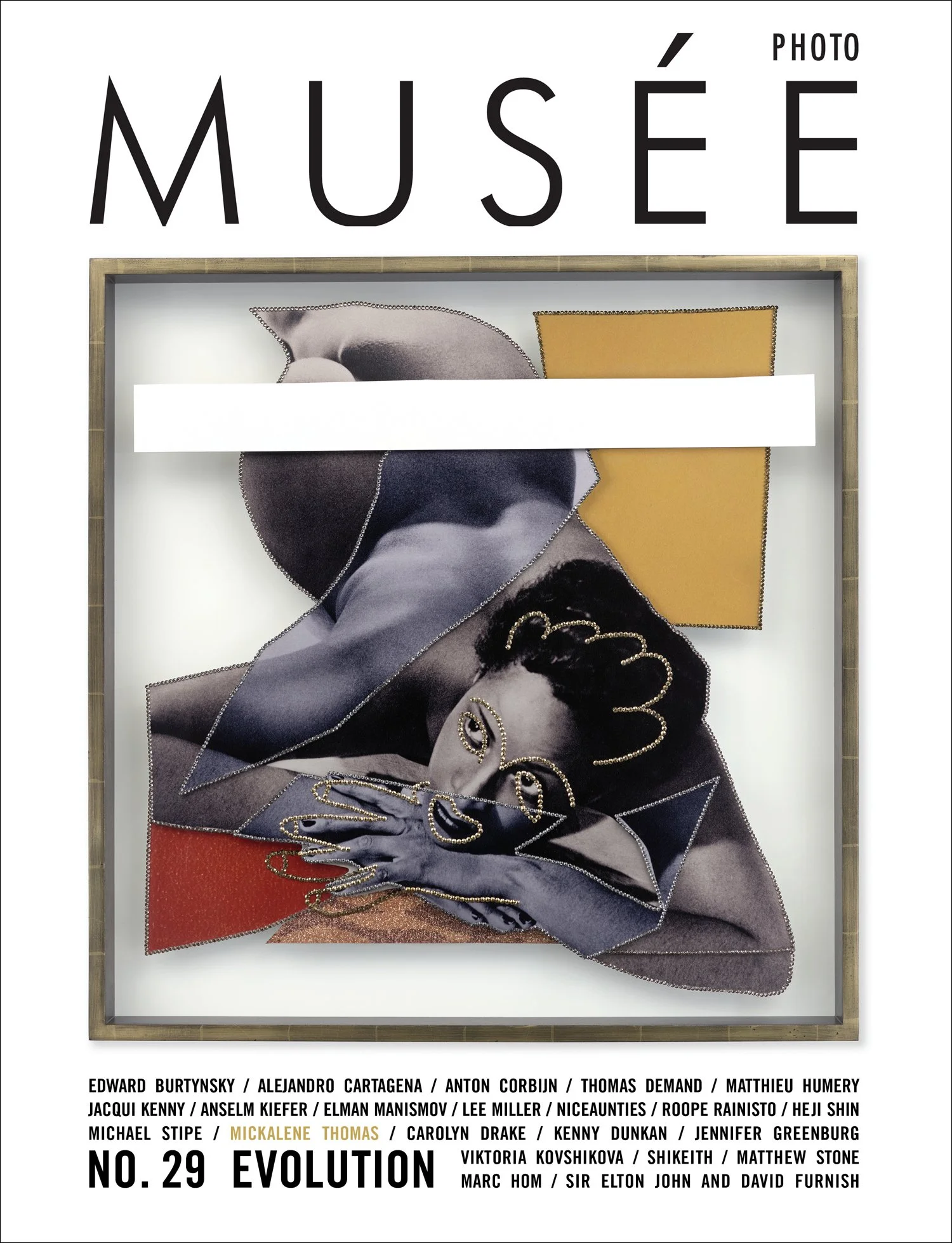

Michael Stipe perceives the photographer's role as that of a mirror to their era. Throughout his career, including his time as the enigmatic frontman of R.E.M., he has seen photography as an extension of his memory. Acknowledged as a profound influence on musicians such as Thom Yorke or Kurt Cobain, Stipe humbly shares how he tries to remove his ego and himself in his photography and publications. In this interview he sits down with one of our creative directors and talks about how his books— each portraying an evolution— show distinct interpretations of the analog and digital worlds. He talks about his heroes, artists, and photographers who helped shape his style.

MATTHEW KRAUS: The theme of this issue is “evolution” and you came to mind as someone who first entered the cultural zeitgeist through music, but you’re also a visual artist who has worked extensively in fine-art photography, and not just during your time in R.E.M.—the imagery and graphics you created for the album New Adventures in Hi-Fi [1997] being a particular standout moment. In the years since R.E.M. stopped making records and touring, you’ve released three books of photography. You also had a show recently in Milan.

MICHAEL STIPE: That’s right. And the fourth book (Even the birds gave pause, Damiani, 2024) is coming out around that show as kind of a loose catalog. It’s very loose. But it’s overlapping. I put the book together at the same time I was putting the show together, and I included a bunch of stuff about process because it’s not just photography. It also includes sculpture and a video piece. I was meant to do a show in 2020. But of course, the whole world shut down and then again and again. Finally, it’s happening now. I’m actually glad now that I had this much time to put it together because it’s completely different than it would have been.

Michael Stipe, Untitled.

MATTHEW: I’m sure. In fact, all your books in one way or another seem to have been parlances of their time.

MICHAEL: I mean, to me, that’s the job of an artist, which is to kind of examine the present in a way that helps push it forward in, I hope, a progressive and hopeful and good way. That’s our calling. That’s the work. The last book—it’s interesting that you say that, I’m looking down at my studio copies of the book and some paint chips. But it’s interesting that you see them as cohesive… I do see them connected. I wouldn’t expect anyone else to, but I appreciate that.

MATTHEW: I found a wonderful quote of yours where you said that, “Photography has been with me as a thing since I was 14. And it became a primary way for me to keep a diary, to remember the moments, the people, to photograph things that I found beautiful.” It seems as though you’re speaking to the idea of photography as memory.

MICHAEL: Yeah, exactly. That’s precisely what it is for me.

MATTHEW: In the audio companion you recorded for your third book, (Michael Stipe, Damiani, 2021) you say you have attempted to remove your ego and self from the book. But I actually found almost more of you in that third book than in the others. The first two are so observational, but the third one references so many things that are important to you. It almost seems like even amore complete picture in some ways of who you may be.

MICHAEL: Thank you. That just means so much to me because I find the third book to be quite flawed, but in a very human and beautiful way that exactly reflects the moment that we were all moving through with COVID and lockdown. With the third book, I started out to do a very clear and simple homage to Richard Avedon: to photograph strong, vulnerable, courageous women in my life who I found to be inspirational. I started with a couple of people who I was able to photograph with a white-walled studio, with an extremely classic composition before COVID shut us down. And the book to me reflects now... I went a little bit cuckoo... I went a little insane during COVID. I think a bunch of us did. And I was in a situation where I had to be very, very diligent and cautious. So I went a little nuts. That book, I think, in a very beautiful, flawed way, reflects that nuttiness.

Michael Stipe, John Giorno.

MATTHEW: There’s a wonderful abstraction to it in many ways—and that stands out to me, especially with regard to how many perceived some of your early lyrical work in R.E.M., where there was a romantic abstraction that became slightly more specific and detailed later on. But that is what I saw as a progression through the three books. I believe with the first one, if I’m right, there were around 37,000 pictures that you eventually edited down to 32—and that editing can create a totally different narrative. However, the concept of the third book, as much as you say it came out of some sort of COVID insanity, seemed like it was much more pre-determined to me, even though you say the process was born out of necessity. It feels the most—

MICHAEL: Cogent.

MATTHEW: Cogent, yeah.

MICHAEL: Yeah, that’s wild. No one has said that to me. So thank you. And I’ll accept that interpretation, absolutely, with open arms. Yeah, to me, I realized probably around 2005 that I didn’t think anyone had done great sculptural representation of who we are, of humanity. That’s now happened. But I started exploring the idea of what is a portrait and what does a portrait consist of. And historically for myself, going back to the first book, but for me, going back 30 years, the only photographs I ever took of Kurt Cobain were of his hands. And that was an absolute choice in the moment. We were friends. We were in a very intimate space. And to photograph his face, it just felt intrusive and wrong. So I didn’t. But I did photograph his hands. And then I asked myself - because it’s not like I can go back to him, he’s no longer with us, and say, “I want to do another portrait.” - what is a portrait? And so, yeah, in the third book, I’m kind of exploring that. And it continues now into the fourth, which I’m happy to say that I think it’s really landed in a very wild place because it winds up ultimately being a portrait of me. And that’s so wild to me. It’s exactly what I’m trying to push away from.

Michael Stipe, Untitled.

MATTHEW: To that point, in the third book, you open with lists of names and then of course you move in and out of other topics throughout. But most of the book winds up being, in one way or another, a list. To me, that says so much more about you even than some of the earlier abstractions.

MICHAEL: That’s beautiful. I mean, it really started as one thing and became something very different. And if our subtext here is evolution, that, for me, was a quite interesting approach. I wanted to make a book. No one knew how long COVID was going to last. I was in absolute lockdown. I was like, “Oh, I’ll just go into my archive and I’ve got these 37,000 images that no one’s ever seen and I’ll just pull from that.” And then I was like, “No, no, no. Wait a minute. The job of the artist is to comment on the present. And so the time will come when I can go into my archives and we can look at that. But this book should be about right now.” So it did become that. I called Caroline, my friend who is a ceramicist, and said, “I’m in a pickle. I need representation of people. Will you make faces? They don’t need to be funereal. They could feel celebratory. But I really just want you to do whatever you’re doing, whatever inspires you and interests you right now as an artist. Do that and put this name on it.” I gave her a list of names of people that she also deeply admired. And we were able to pull that off. I then photographed—and they are photographs. It’s documentation. But I then photographed her vases one at a time.

Michael Stipe, Kurt Cobain's Hands, 1993.

MATTHEW: But there were choices in terms of how you photograph them. There’s a starkness, as if you wanted them to stand alone and not with a drama that surrounds them other than the name.

MICHAEL: Thank you. Thank you very much. I mean, that really means a lot. You put some thought into this. I really appreciate it. What wound up happening with the vases is that the way I was photographing them, they looked Photoshopped—and I liked that. Like the books I photographed that are opened, where you can see that it’s pasted and cut and exploring all these really intentionally wacky kind of 1970s fonts. I liked that it felt like something that it wasn’t. What it was was actually an extremely classical form of photography, and in my situation at the time, a portrait.

MATTHEW: Right. I mean, listen, its not a stretch to interpret that starkness as if it’s an Avedon portrait.

MICHAEL: Thank you. I mean, I’m looking at his books right now. That was the inspiration in the first place. That’s why Tilda Swinton was on the cover, looking like she does. We’re great friends, and she’s very easy to photograph. You can imagine. What she gave me—how she opened up—was, for me, extraordinary and so much more about her abilities as an artist than my ability to document an image of her. But it was this beautiful kind of kismet... I mean, I got the image I wanted and I knew when I got it. I was like, “That’s it.”

MATTHEW: Well, that’s certainly Avedon-esque as well.

MICHAEL: Yeah. He was very decisive, a word that I don’t like to associate with photography. But I also had the opportunity to meet and hang out with him. He sent me a really beautiful gift once. So anyway, his work, the person that he was, was, for me, quite magical. His work, to me, is on par with the very greatest that we have ever had, going back into history.

MATTHEW: Of course. And the blue tint? I wasn’t sure if I saw anywhere where you spoke to that specifically.

I started exploring the idea of what is a portrait and what does a portrait consist of

MICHAEL: I don’t think I spoke about it. Originally, the project was all women. And then John Giorno, who was a dear friend and mentor, died unexpectedly. When I heard of his death, I was landing in Europe. I turned on my phone and got the news from a friend that John had died. And in my bag I had a draft of his memoir and a role of film that was unprocessed, of what became his final show. I’d gone to the opening and said, “John, come here.” I photographed him against the wall, with a couple of his pieces. But the film was unprocessed in my carry-on bag and the draft of his memoir was three-quarters read when I landed. And I just looked down and went, “Fuck.” And at that moment, the project became very different.

MATTHEW: In the audio companion to the book, you speak about John’s attempt to see beyond the ego... To come full circle back to what we said about seeing yourself or not seeing yourself in the third book. It just goes to prove that removing yourself and your ego from the center is always a process and never a destination. Where did the desire to do that come from? I mean, for so much of your career you have been someone who is literally front and center.

MICHAEL: The first book feels very diaristic to me and historic. So it starts almost at the beginning of my life—as an adult anyway—and then moves forward through time. The second book is really, for me, an examination of where I feel like we are between a completely analog world and a digital world. And now I’m addressing the digital revolution that’s begun and that we’re in, but digital disguised as analog, which I also find fascinating. We’re in this very weird, very layered in-between space, visually.

Installation views, Michael Stipe. I have lost and I have been lost but for now I’m

flying high, ICA Milano, Italy; Curated by Alberto Salvadori. Photographed by David Belisle, 2023.

Installation views, Michael Stipe. I have lost and I have been lost but for now I’m

flying high, ICA Milano, Italy; Curated by Alberto Salvadori. Photographed by David Belisle, 2023.

MATTHEW: In so many ways I think.

MICHAEL: Right. [laughs] And then not only how we receive and accept visual imagery, but what it looks like and how it’s broken down in our actual vision. I mean, one suggestion was, because of pixelation and because of the natural fractals that occur in nature, that digital was maybe perhaps bringing us even closer to some understanding on a very microscopic, molecular level of who we are and where we are in this world. So that’s absurd and a little...

MATTHEW: Listen, compared to so much of what we are seeing now, that’s not so absurd. I mean, the idea that everything is this holographic moment, to me seems perfectly reasonable.

MICHAEL: Well, well.

MATTHEW: It’s interesting because in the audio companion you also express a fair bit of optimism about how we will hopefully emerge from COVID and that moment. With, albeit, a relatively short distance from that time, do you hold that optimism?

MICHAEL: [laughs] I don’t remember what I said, to tell you the truth.

MATTHEW: [laughs] I’m paraphrasing, of course, but you said something to the effect that you hoped and believed we’d come out of that collective trauma unified in some way around our humanity. I did hear optimism in it, ...well, maybe it was my need to be optimistic, but if you don’t recall the optimism, maybe it’s hard to speak to it.

MICHAEL: No, no. Even in the dire moment that we find ourselves in right now, I remain optimistic. There’s anger wrapped up in there as well, and there’s a lot of aspirational hope. But I am ultimately an optimist.

MATTHEW: Do you think the new work reflects that?

To me that is the job of an artist… to kind of examine the present in a way that helps push it forwards

MICHAEL: That optimism? Yeah, totally. And actually, the upcoming show that the new book is kind of about is addressing a hopefulness in spite of terrible times. And we don’t need to get specific about that. But this has been a magnificent, awful several years for just about everyone on earth.

MATTHEW: So...“We are hope despite the times?” [laughs]

MICHAEL: [laughs] I mean, I’m not going to quote myself, but if you want to... No, of course. I mean, it’s exactly that. Of course, it is. “We are hope despite the times.” That’s really what the show is about. Hopefully, a bit of a respite, a place to rest for a moment, as well to just reflect on the things about us that are magnificent and glorious and aspirational and desirable and progressive and not the kind of slide into mundane hardness that we find ourselves in right now.

MATTHEW: I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t appreciate that. So back to process. You’ve said before in writing most of your great songs, you saw landscapes and then you had to people them to create a narrative that works within that landscape. Do you find that there’s a reverse with that process in photography? It seems as though from the imagery comes the story. Or is it happening simultaneously? Or in parallel?

MICHAEL: Yeah. The photography is—and I’ve had people around me tell me this, my most intimate friends and my most inner circle—that I see things very differently than most people. I do have an eye for detail that’s almost pathological, but I see things that other people just don’t see, so that’s what I tend to be interested in photographing.

MATTHEW: That’s interesting because I read a musical quote of yours as well where you said that you were told you hear things differently, to. Because you came to music without classical training, you placed your lyrical cadences in places that people just wouldn’t expect. Even your bandmates would say, “Well, when we wrote this piece, we didn’t hear those things there...” I mean, it’s probably just part of your artistic DNA.

We're in this very weird, very layered in-between space

MICHAEL: Absolutely. Along with the list thing. The list thing is quite specific. But I’ve met other people who have the same... They organize their brain that way. It’s not by choice but they organize things in the same way with lists. And that goes back to the songs. The one everyone knows, of course, is “It’s the End of the World as We Know It [and I Feel Fine].” But there’s a whole category of R.E.M. songs that are lists and nothing more. The song “Departure” or “I Remember California.”

MATTHEW: That’s interesting. Those holographic sort of pixelated things permeate the work. I also want to speak to the evolution of your photography as a career—

MICHAEL: [laughs]

MATTHEW: —well, not as a monetary one necessarily, but more as a singular artistic pursuit.

MICHAEL: I was going to say when it starts paying the bills, I’ll let you know. [laughs]

MATTHEW: [laughs] But the idea that a lot of times people picture evolution as a trajectory going in one particular direction. The truth often is, though, very different. Do you see an evolutionary line through your work as a photographer or your work within photography as a medium? The way you see as a photographer, do you see that in a particular lineage of photography?

MICHAEL: Oh, I don’t know if I have a lineage, honestly. Musically, I was just surrounded by people who knew music, and I didn’t. I mean, I knew a very specific, a very tiny sliver of music that was really super inspiring to me. But in art I could easily list artists who have deeply inspired me and who have actually altered the way I take pictures. I remember at one point, Jack Pierson put out a book that was so astonishing. And Wolfgang Tillmans had a book that was astonishing. Both of their books were in color. And I was like, “That’s it. I’m only shooting black and white.” Because I felt like even… The influence is there. It’s always in the back of your head. But I didn’t feel like I could do better than them in color. So I instantly went, “Okay, I’m shooting black and white.” That’s that. And I did that for four or five years, and then I moved back into color again. Now I shoot both, but I differentiate. Color is strictly digital. Black and white is strictly film.

Michael Stipe, Tilda.

MATTHEW: Jack’s last show was incredible.

MICHAEL: That show blew my fucking mind. That show was so majestic. Particularly the very end, if you were moving clockwise around the room, it ended with a vitrine that he had exploded and cut out of plywood, painted silver with these crazy shades that were inspired by tramp art and then filled it with items from his past that were inspirational to him. For me, there was a throughway there from my Infinity Mirror at the Journal Gallery and the idea of a thing that is showing influence. And Jack, of course, is one of my influences. So it’s nice that we share that. But along with those guys, the day before yesterday, I saw a book of Josef Koudelka chosen from his contact sheets, and Koudelka was, at one point, my favorite photographer in the world. And I had the opportunity to meet him. He actually handed me the camera and said, “Take some pictures while I pour some whiskey.” We were in a broom closet. I mean, it was insane. But I was like, “Fuck, I’m holding his camera.” I couldn’t believe it. [glances to his right] Sally Mann was wildly influential to me. Peter Hujar—wildly influential. Who have I said? Claude Cahun blows my mind. And her photography work has gone on to inspire contemporaries of mind who I admire a great deal. Man Ray was also wildly influential… And I’d certainly be remiss not to mention Andy Warhol because, as a photo-based artist, his influence still resonates on a level that I think is unique coming out of the 20th century. I don’t think any artist has had more resonance, generationally speaking.

Michael Stipe, Sinéad O'Connor vase by Caroline Wallner.

MATTHEW: Is that a bookshelf over there?

MICHAEL: That’s my bookshelf, yeah, but I can’t see it. We’ve also been juggling our books. We moved into a new place here and we’re trying to get rid of a bunch of them, but it’s not easy.

MATTHEW: As long as people still find them precious as objects, I think we are in good shape. The art book does seem to be the one thing that’s avoided a complete digital makeover. So far, so good.

MICHAEL: Thankfully.

MATTHEW: But who knows?

MICHAEL: If a giant meteor or some human alliance decides to magnetically wipe out everything digital, then we’ll at least have our photo books.

MATTHEW: I saw another quote of yours that I found amazing, That it wasn’t until around 2005 that you realized you had a distinctive singing voice.

I am ultimately an optimist

MICHAEL: I honestly didn’t know that. I did not know it. I did not realize. I mean, there were a few times when I would call some random 800 number and be talking to someone and they’d say, “Is this Michael Stipe?” And I’d say, “Yes.” “How did you know that?” “Did my name come up?” And they’re like, “No, your voice is…” I’m like, “What? Really? Oh, wow. Okay. Well, nice to meet you, Judy from accounting.”

MATTHEW: [laughs] Can you identify your distinctive voice in your photography?

MICHAEL: Oh, I think so, yeah, very much.

MATTHEW: That’s interesting it came so much faster.

MICHAEL: Well, I don’t think I’m a great portraitist. I’m living with one. My boyfriend is an astonishing portraitist. I’m surrounded by them. Our great friend, David Belisle, does incredible work—he did the pictures of Sinéad O’Connor that were just in Rolling Stone of her in a really beautiful moment for her. I’m surrounded by people who are really inspired and really great portraitists, including Jack [Pierson]. We don’t text each other on a weekly basis, but his work has definitely left an imprint on me. Wolfgang [Tilmans] as well. I’ve known both of them for decades and really admired and loved the choices that they’ve made and the evolution of their visions. Wolfgang always challenges me with his abstraction because sometimes it’ll take me a year to figure out what he’s doing. I don’t really want to read about it. It’s like a movie. André Kertész, I would throw in there. I knew that there was someone else. [glances right again] Black Mountain College was wildly influential to me. Sophie Calle, too.

Todd Eberle, Me with Andy Warhol, Beacon Theatre, NYC 1995.

What a life I’ve had. And who would ever imagine. Talk about evolution...

MATTHEW: I just saw the Sophie Calle show at the Picasso Museum in Paris.

MICHAEL: Did you see my piece in it?

MATTHEW: I don’t know. Where was your piece?

MICHAEL: I had a piece on the Guernica wall. It’s a bronze replica of a cassette tape.

MATTHEW: Oh, well, then I did see it. That wall was astounding.

MICHAEL: Sophie Calle is magnificent. She’s just so profoundly incredible. She did a show in the Musée d’Orsay. They approached her and she said, “I know more about this building than you do.” And they were like, “Excuse me?” She had basically used that building when it was abandoned before the museum moved into it in Paris. She used it as an office and as a place of inspiration. And she would break into it. It was a completely empty, enormous building. And then she would collect things like doorknobs and notes and keys and little things. And she kept all of these stashed away for decades. The building, which is a former train station with a hotel in it, then became the museum. And she did the show about basically the history of the museum through these objects… Well, she was asked to do it, and then COVID happened. And her response was to ask for permission to go into the museum while it was closed because everything was in lockdown. And she found the paintings that she loved and photographed them as they were. So they’re extremely dark or they’re lit by a flashlight of whoever was moving her through. And it’s like Manet, Van Gogh, the great painters of our time—and she’s rephotographed them on the wall in practically complete darkness.

Michael Stipe, Slava Spin.

MATTHEW: That’s such an interesting interpretation of what someone looking at art might want to see, which brings me to something else I wanted to ask you about performance in general. Your personal approach to performance has evolved so much over the years, from a noteably shy era in your singing career in small clubs, to projecting to the back row of some of the biggest arenas. Do you think about the concept of performance when you’re doing photography in terms of what the audience is taking from the work?

MICHAEL: I don’t think about performance while taking still images, but I have moved into some video pieces. With those, I’m actually going to people whose job is performing, mostly dancers, and asking them to perform under very questionable or rigorous circumstances. So I recorded a track that’s a really, really badly written disco song, like intentionally bad, and asked them to move to it—I asked professional dancers to move to this track. And then I pull the track away. I edit together, with my limited knowledge of contemporary dance, what I consider to be their best moments, and then silence the track completely, and I compose to their movement. It was a nice kind of exchange that happened. That’s completely performative. I mean, we know from Sally Mann now that the kids who were a part of her best-known body of work, her three children, were a part of it and understood the theatricality of what she was doing and allowed all these kind of things to happen to exaggerate or bring to some operatic, ecstatic high a very mundane or simple moment, like vomiting on a bed or having a black eye or taking off a cast and seeing the dark hairs. Sally speaks about this openly. They went in with mascara to make the hair darker. The kids were a part of every photograph. So that’s a beautiful thing. Early on, you referred to my work as a fine-art photography, and I don’t think of it as such. In a very loving way and respectfully, I feel like I’m more of a snapshot photographer, really. I’m quite classical in the way I see things—or the way I frame them, rather. But what I choose to photograph is probably different from what other people would choose to look at. And it’s not about elevating some little moment. Wolfgang is really good at that, I think. But it’s more about looking at an object or the way the light plays off of something in a way that you wouldn’t necessarily see it before. And it can become tiresome. I mean, the way I’m talking right now, this is uncaffeinated. [laughs] I’ve just woken up from a nap. I’m quite tiresome in person. I never stop. And the way I see things, I’m like, “Whoa, look at that!” And there’s this element of always seeing and always being distracted by everything around you. That said, it’s nice that the people around me can say, “The way that you see the world is really fascinating because nobody sees it like that.” So that’s kind of nice. That’s what I would hope the books are achieving, presenting these different kind of fractal viewpoints onto how I see things and then onto what I consider to be an incredibly lucky life. I’ve been able to experience meeting heroes, working alongside heroes, having normal conversations with heroes about art and about the process of editing your own work, etc. What a life I’ve had. And who would ever imagine. Talk about evolution, that I would go from what I was as a very young teenage boy at the age of 14, who became interested in photography, and at the age of 15, music came in and kind of took over… But luckily, I think I used photography all along as a way of creating for myself a journal and being able to remember the moments of this extraordinary life—and then, hopefully, piece them together in ways that are illuminating and exciting for other people to look at. You just need to be there. You don’t even necessarily have to know who these people are. But there’s something in that look. There’s something in the glimmer of that eye. There’s something in that landscape that is different from the way you’ve seen it before.

Michael Stipe, Sophie and Paddy.

Micahel Stipe, River asleep West to east, Los Angeles to Athens, 1993.

MATTHEW: I think that’s an absolutely wonderful place to end. And I have to say that, as you said, finding yourself in a life where you’re sitting with your heroes, I’d be remiss not to say that I feel that way now.

MICHAEL: Wow. Thank you so much.

MATTHEW: I’m so appreciative of you taking the time.

MICHAEL: Yeah. No. I’m excited for the piece, and I’m really happy to participate.

Micahel Stipe, Martha.