Image above: Phillip Toledano (Portrait by Andrea Blanch)

ANDREA BLANCH: What advice would you give to an emerging photographer?

PHILLIP TOLEDANO: You’ve got to be shameless, and by that I don’t mean in terms of promoting yourself. You’ve got to be shameless about the way in which you make art. You can’t make art with the idea that people might not like it, that it might be viewed as one thing or another. Your heart has to be on display, however it manifests itself. If you hold back, then it’s visible in the art and then it’s not good art.

AB: Why did you choose photography?

PT: Because it was the thing that I could do. I had been doing it since I was 10 or 11.

AB: Do you go to photography shows?

PT: No. Actually, I don’t find photography that inspiring. I find painting, sculpture, or installations much more inspiring. I had this epiphany a few years ago that the thing that interests me the most is the idea. What is very liberating for me is to let the idea be the thing it wants to be when it grows up, rather than trying to shoehorn this idea into pictures. Some ideas are not photography at all. I just finished two new books, one of which is performance based, which has been really excruciating.

AB: Are they selfies?

PT: They’re self-portraits, yes. After my mother died suddenly I became apprehensive of my future. I thought about the ways in which life can take a sudden, sharp turn. I thought rather than worry about it, I would confront my fear head on. I just finished this project, called “Maybe,” where I took a DNA test that told me what illnesses I am likely to get, and then I spoke to fortunetellers, psychics, and tarot card readers. Based on all this information I made photographs of my future, of all the dark things that could possibly happen to me in the next 40 years.

AB: How did you express that photographically?

PT: Based on the DNA tests that said, “OK, you have a high chance of obesity or you have a high chance of heart disease, or…” I worked with a prosthetics person, I spent 45 hours to get into makeup, and I took acting classes. Then I acted out that version of myself.

AB: You needed acting classes for that?

PT: You need to learn how to be a man of 94. How do you move? Or how do you move if you’re obese? I had to inhabit possibilities of myself. I hated doing it. First of all, I’m not a very patient person so sitting, waiting, and prosthetics for 4-5 hours is miserable. I don’t like being in front of the camera and I had to learn how to act. Most of the time I wasn’t taking the pictures, I wasn’t even framing them. My assistants were taking them. I would think, “Why are they off kilter like that?” It would make me crazy because it’s very important how a picture is framed, but I had to give that up. But it was interesting because you don’t usually get to be 95 and then 45 in the same day. I’m not saying that I could feel exactly what it was like but I had a very vague feeling of what it might be like...

AB: Would you like to live till 95?

PT: My father lived till 99. I would only like to live until 95 if the people I loved were around still. But it was interesting because when you’re 95 in a wheelchair and pushed around by a nurse, you’re invisible. Or people avoid you. When I was really obese I was invisible. Everyone has a kind of sonar and you register on that sonar. Everyone registers each other. You get a ping back. You are part of the topography. And at some point you don’t register anymore.

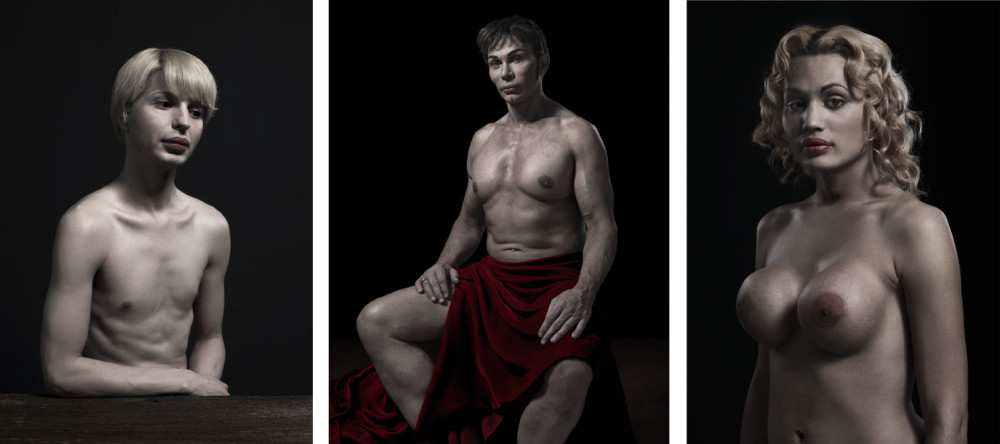

©Phillip Toledano, (Left:Angel; Center:Steve; Right:Paris)

©Phillip Toledano, (Left:Angel; Center:Steve; Right:Paris)

AB: People avoid you.

PT: Well, they avoid you if you are at the end of your life, in a wheel chair. People don’t want to look at you. There is one photograph where I’ve had a stroke so half of my face is paralyzed; people wouldn’t look at me.

AB: Let’s talk about “A New Kind of Beauty.” How did you come to this?

PT: I did a book called “Days of my Father” about my dad, and about taking care of my dad. I did a “New Kind of Beauty” at the same time. Then this project, “Maybe,” is the final chapter of that series.

AB: How do they connect?

PT: “Days of my Father” is about my father’s mortality. “A New Kind of Beauty” is about the idea of mortality and rejecting mortality. If you think about what plastic surgery is, it’s the idea of denying death. It’s saying, “I’m not going to age.” In a way it’s about myself but I am not visible in that project. “Maybe” is about my own mortality where I am fully visible in it. When I was a kid in 1985, someone with a tattoo or a piercing was considered outlandish. Now, it’s totally normal. I think that the idea of what it means to look human may be very different in 30 or 40 years time. I find it interesting to consider that what it means to look human might be very elastic. If beauty is readily available to anyone, then beauty means nothing. The currency of beauty is devalued. What’s interesting in the book for me is that people aren’t interested in being traditionally good looking, they want to look like an animal or anime character. That’s expanding the idea of what it means to look human.

AB: How many people want to do that?

PT: More than you would imagine! And that’s fascinating to me. I find it inspiring that they are not saying I want to look like Johnny Depp. They want to look like a cat or a character from a Japanese cartoon. They are not going to look particularly human but they could look interesting and beautiful in their own way. But I don’t think the technology is sophisticated enough. It’s a little bit primitive which is why I think people look slightly similar. We are at the beginning. As a race we’ve always wanted to change how we look. It’s just now the technology is really there to change us.

AB: You think everyone wants to change the way they look?

PT: No, not at all. There’s always been a desire or pressure to change how you look. I don’t think everyone wants to change. But, for instance, go back to the tattoo thing; I think 65 percent of people under 25 have tattoos or something extraordinary. Maybe in 30 years time it will be like that with plastic surgery.

AB: How long did it take you to complete this series?

PT: I think it was two years.

AB: How many people did you photograph?

PT: 26 or 27, most of whom were in the book.

AB: What did you think of those people?

PT: I will say this: everyone I shot was very happy. They had all had multiple procedures and they were happy and proud with the journey they were taking. It’s no different than when you see someone on the street and you see them wearing something unusual. That person looked in the mirror in the morning after they got dressed and said, “I look good!’ It’s no different.

©Phillip Toledano, (Left:Fred; Right:Justin)

©Phillip Toledano, (Left:Fred; Right:Justin)

AB: But all they have to do is change their clothes.

PT: I’m not talking about the permanence of things. I’m talking about the mindset. I’m talking about the way in which we see ourselves. There’s no limit to the power of human delusion. How we can delude ourselves about how we look, about what we say, how we feel. There are no boundaries to that. Someone looks in the mirror and thinks they look good and they feel happy with that. That’s all that matters.

AB: What do you think about Sandro Miller’s “Malkovich, Malkovich”?

PT: I think that it’s smart, funny, witty, and really well done, but I prefer art that tries to do something, say something. To me art is interesting when it opens doors or makes me consider vistas that I might not have considered.

AB: How would you define beauty?

PT: I don’t know. It’s impossible. It’s like saying, “Talk about air.” Do you know what I mean? “Talk about sunlight.” How can you define it? It’s a thing that either is or isn’t for each person.

AB: Do you believe your subjects are artists? Creating their own beauty ideal?

PT: In “New Kind of Beauty?” Yes, I think so in a way. I believe they are on the journey of recreating themselves in some way or another. I would have to ask them if they think they are artists or not. Some definitively. There’s a guy called Justin, who’s actually in the news these days. He’s known as the “Human Ken Doll,” and he really thinks of himself as some kind of art piece in progress.

AB: What’s the end goal? Does he know yet or he just keeps going?

PT: I don’t know. I think it’s kind of like the “Maybe” project. It’s the journey not the destination if I am going to be all 1960’s about it.

AB: Why did you choose to photograph them in the way that you did? In the classic style?

PT: I wanted to make very beautiful, dignified portraits of these people. I just wanted it to be simple. I didn’t want to distract.

AB: I had no idea you felt the way you do about photography, that you don’t find it inspiring.

PT: For me, photography is a tool in a toolbox. It’s not the thing that I do. Do you know what I mean? There’s a difference. When I have an idea I think of how it’s best expressed, not how it’s best expressed in photography. That’s not to say I don’t see photographs or see projects and think, “God, that’s fantastic.” But when I look for inspiration I go to the Met and look at 16th century oil paintings. In part, I think that’s because I am pretty limited. I am not a person who can paint. I did a project with paintings, but I didn’t paint them. I had someone else paint them. Did you look at the project “Kim Jong Phil”?

AB: No. What is it about?

PT: I think a lot about how I function as an artist. It occurred to me that to be an artist, I have to have a couple of things. One is to be narcissistic and delusional. I need to imagine that I have these ideas that no one else has had before. I have to imagine that the world is just waiting for what I have to say next. You have to create this little world and live in it. It’s much like being a dictator. I’ve always been fascinated with Kim Jong-Il and North Korea, so I did “Kim Jong Phil.” I found images on the web that people have taken of propaganda art. Then I had it copied in China as an oil painting with me as a dictator. I also did a bronze sculpture.

AB: So, you’re a narcissist?

PT: I think that, certainly, if you make art, some part of you has to be narcissistic. Unless you’re making art for no one to see, some part of you has to imagine that people are going to be interested in what you have to say. I mean, frankly, I find it surprising when some people are interested because, really, why would they be? I’m just talking about myself and I’m not that interesting, except to myself. Half of me thinks, “I have something interesting to say,” and the other half thinks, “Are you nuts? Of course you don’t have anything interesting to say.” It’s a conflict. But to make art, for me, I have to have that dialogue with myself. That’s the delusion. The reality is I make the project and I put it out there and the world decides if what I am saying is interesting. I don’t. That is exactly the same as the way you look at yourself in the mirror when you’ve had a little plastic surgery. It’s delusion. It’s the fuel that runs us all.

AB: The theme for this issue is vanity. So, how might your definition of vanity pertain to “A New Kind of Beauty”?

PT: Well, I can’t say. It’s not for me to speak for them. Most of us, to a greater or lesser degree, are interested in how we look. It’s a question of how interested you are. If you’re asking me to say, “I think these people are vain,” I won’t say that. That’s not the point of that project. I was interested in where they were going, in talking about the idea of mortality and the idea of what it means to look human. The “Maybe” project has also been a journey for me in terms of confronting fear and coming to grips with mortality. It’s about letting go of vanity, too. In some of those pictures I am wildly unattractive and it’s been fascinating to feel that way. I cast all these young, attractive people and they show up at the studio, I am already in costume and makeup, and they see me and think of me as that guy. I know on the inside that I am someone slightly better looking than that guy, but I don’t care anymore.

©Phillip Toledano (Monique)

©Phillip Toledano (Monique)

AB: What fear is left to be tackle in your repertoire?

PT: “Days With My Father” was a real revelation for me because I suddenly realized it was a way for me to have a dialogue with myself about things that mattered to me. It was a way of figuring stuff out. So I did “Days of My Father” and then I did “The Reluctant Father,” which was about Loulou.

AB: I thought it was so honest. I loved it.

PT: Funny enough, almost universally, women said to me that they loved it and men often say they are outraged by it. I spoke to Carla, my wife, about it and she thinks it’s because women have been mothers for millennia. The idea of being a father is what, 50 years old, even less than that. For dads, the idea of fatherhood is this sacred, beautiful, crystalline thing. For me to come out and say, “Hey, I didn’t really like it for the first year,” is sacrilegious. I wasn’t saying I wasn’t willing to do what I had to do, just that I didn’t understand it and I didn’t like a lot of it.

AB: You said that Loulou is beautiful. So, besides the fact that she’s your daughter...

PT: That’s one of those things. I don’t know if I say things just because I am her father. I have no objectivity with Lou at all.

AB: So there’s nothing specific that you think is beautiful?

PT: Well, beauty is beautiful. If I see a beautiful woman, I think, “Oh god, she’s beautiful,” or a kid, or a sunset.

AB: What about this woman is beautiful? I want to pin you down!

PT: It’s impossible to say! It’s like an algorithm or a mathematical formula that just all works together. It’s a certain kind of nose or it’s a certain kind of hair. It’s hard to say because I am attracted to all different types of women. Like, my roommate in college really loved Asian women. That was his thing. But I don’t have a thing. I’ll tell you what I do find, though, I am always astounded by beauty because it seems so unlikely, particularly when you see someone who is really extraordinarily beautiful. They seem like a different species at first. Because there are so many ways in which we can go wrong physically. Everything has miraculously happened to work all at once. At the same time, I have no interest in it artistically. I’ve got no interest in taking pictures of beautiful people because it’s boring. How hard would it be to make a beautiful person look good? What more is there to the story?

AB: What’s left for you to accomplish?

PT: That’s it, I’m done! I’m retiring at the end of the year. I would like to have a retrospective here in the States. I’d like to have a good gallery. I used to have a few galleries, I used to have one in Philadelphia. I had one in New York, but it didn’t really work out, same thing in LA. So, I’d like a good gallery. But I have these books, I have a retrospective coming up in Germany, so who could ask for more? Still, on the inside I think I need it. That’s that delusion.