Film Review: All Things Are Photographable

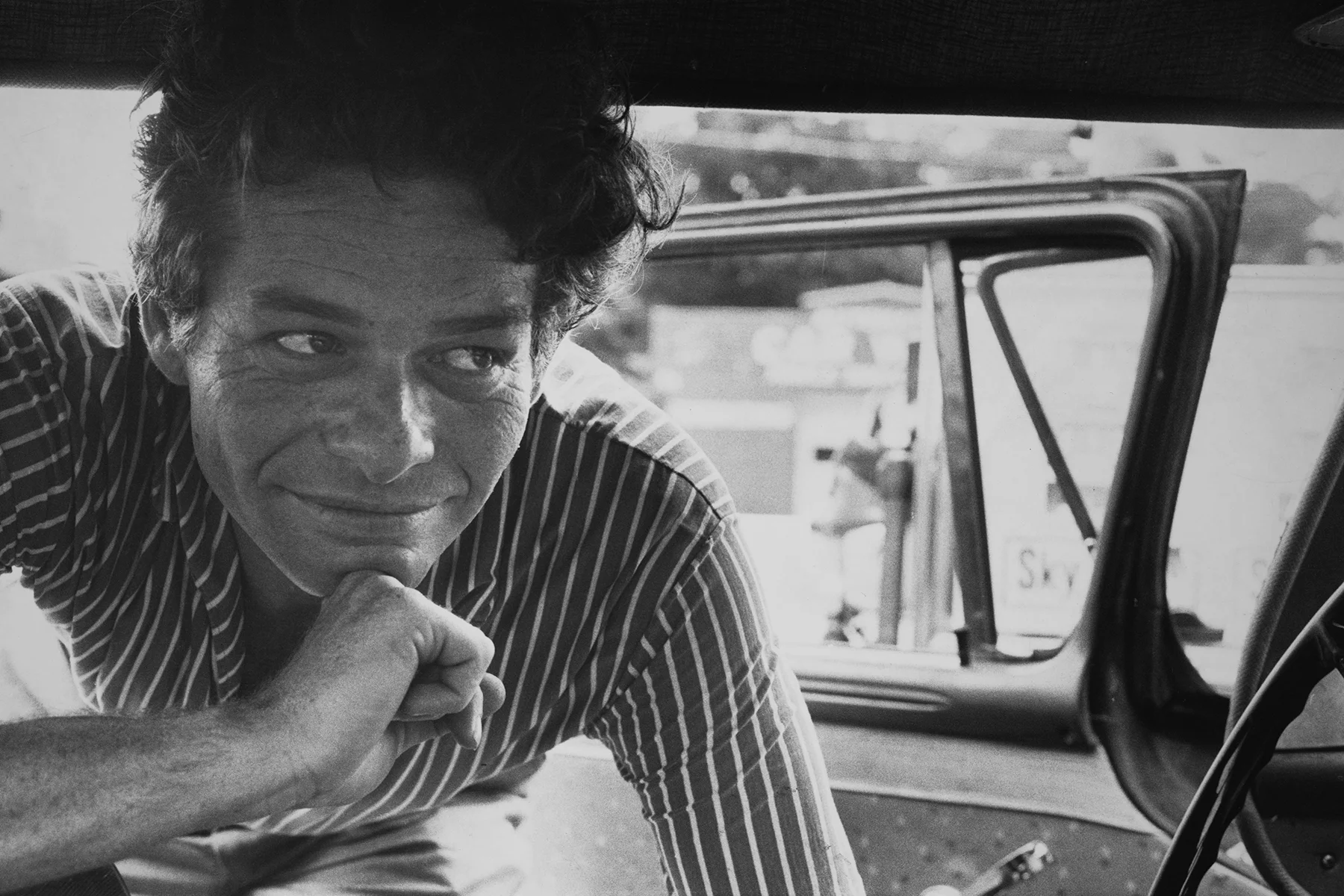

Portrait of Garry Winogrand by Judy Teller © Greenwich Entertainment

By Erik Nielsen

Garry Winogrand’s body of work has the stamina of an olympic athlete. The big-brash Bronx native was often labeled the first digital photographer because of the sheer volume and immensity of his work. He left, in his wake, over a quarter million undeveloped photographs. The wonder that this documentary illuminates is that to Winogrand, all things are photographable.

The director, Sasha Waters Freyer tell us the story of Garry Winogrand in a brisk 90 minutes, exposing us to over 400 of his photographs. While the format isn't groundbreaking there are some wonderful DIY animation sequences that add motion to the array of still images. The director is also able to contextualize Winogrand’s work by interviewing frequent collaborators, family members and art historians. Never before seen and heard audio clips from talks with his close friend Jay Maisel are also revealed. One of the wonderful things crystallized through the interviews and audio clips is his sense of humor. “Do you always use available light?” a student asks, “What other light is there?” Garry replies.

Winogrand’s vision was clear, “You take a photograph to describe.” and his work moved to the forefront in the show New Documents alongside artists Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander. The show, curated by John Szarkowski who was instrumental in Garry’s prominence, would later go on to dismiss his posthumous work (I disagree) which is debated towards the end of the film. The landscape may have changed when he was forced to move to the West coast, but his eye remained consistent, fixed and open, like the 24mm lens he so often shot on, he could see it all. But, Freyer succeeded in allowing her subject, Winogrand, to be vulnerable. The film doesn’t deify the artist but allows critique to be carried out in nuance by the interviewees. Especially when it came to his book “Women Are Beautiful”, which is regarded as problematic by feminists.

Max Ernst once said “When the artist finds himself he is lost. The fact that he has succeeded in never finding himself is regarded by Max Ernst as his only last achievement.” The same could be said about Winogrand. He took to the streets, always, to look for something. He was transfixed by the medium and allowed it to carry him through every discovery, every human intricacy that revealed itself and fit it squarely in his lens. Especially during and after the Vietnam War, when America was going through it’s own existential crisis.

Winogrand had the eye of a poet. His empathetic capacity for the human condition is why his body of work is so expansive. As Freyer reveals to us, an obsessive and loving artist whose sense of discovery was endless.

Los Angeles, 1964_Photographs by Garry Winogrand, Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco