Co-curator Maggie Mustard Discusses: The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Works of Nobuyoshi Araki

© Nobuyoshi Araki , Tokyo Comedy, 1997 Courtesy of Private Collection.

By: Scarlett Davis

Nobuyoshi Araki is one of Japan's most lionized photographers. His photography is synchronous in evoking both erotica, sentimentality, mortality, and controversy. Araki born in the spring of 1940 in Tokyo, has a distingushed near fifty year career and is most prominent for his photography centered on Japanese bondage style kinbaku-bi. This exhibition The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Work of Nobuyoshi Araki is featured at the Museum of Sex until August 31st, 2018. There, featured are over 150 of Araki's prints, 500 Poloaroids, and a glass case displaying 400 of his photobooks. As MoSex illuminates, Araki expressed that 'photography should be immediate, unflinching, and deeply personal,' which has resulted in a oeuvre that Is as sexually explicit and controversial, as it is intimate, grappling also with latent issues surrounding love, loss, and our mortality. Here to discuss the curation that went into the first major retrospection in the United States of Nobuyoshi Araki's photography, is MoSex co-curator, Maggie Mustard.

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Marvelous Tales of Black Ink (Bokuju Kitan) 068, 2007 Courtesy of Private Collection

Scarlett Davis: The layout for this exhibition offers an astute rendering of Araki’s work. Beginning on the second level, the public is thrown into a kind of “Araki baptism by fire,” invoking a kind of shock factor where the photography is centered on his kinbaku-bi(bondage) work and is a bit more titillating and controversial than some of the more sentimental work on the third level, noting the photography of his late wife, Yoko. Could you elaborate on the artistic decision that went into planning the layout and the deliberation that went into introducing Araki to a new, Western audience?

Maggie Mustard: Mark Snyder (Director of Exhibitions for the Museum, and co-curator) and I approached the exhibition structure thematically, rather than chronologically. Because Araki is so prolific, a truly comprehensive chronological retrospective felt nearly impossible within the available gallery space. But perhaps more importantly, a thematic approach allowed us to tell a different kind of story, where Araki’s art historical narrative is fully woven into the social, political, and legal concepts of sexuality in Japan and abroad.

We made the decision to open the exhibition with Araki’s most confrontational and controversial work precisely because these works, their visual language, and the debates that have surrounded them open up onto some of the most complex and interesting conversations that can be generated by Araki’s photography. Knowing that the Museum’s audience is already very diverse (and potentially especially so for this show, in that visitors could be die-hard Araki fans or have never heard of him before), we wanted visitors to feel introduced and educated through a series of questions: Why was Araki’s work controversial in Japan? What were the legal and social norms that his work pressed up against? Why was Araki controversial once his work began to gain popularity in Europe and America? How did the conversation change? What are the power dynamics at play in his artistic process? What do his models say about working with him? What is the role of celebrity and artistic brand in these relationships?

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Blind Love, 1999 Courtesy of Private Collection.

© Nobuyoshi Araki Flowers, Yamorinski and Bondage Woman, 2007 Courtesy of Private Collection

After negotiating Araki’s photography within the context of these questions, the second floor of the exhibition opens up onto themes and subjects with which Araki has a kind of obsessional relationship—they turn up again and again over his fifty-year-long career. Whether the subjects are his wife Yōko, the Tokyo nightlife, or "erotos," we wanted visitors to have context for Araki’s artistic choices. For example, we examine the history of sexuality and art in Japan through a section on ukiyo-e woodblock prints and provide additional information about the history of kinbaku-bi (bondage), while also examining more slippery concepts like Araki’s “sentimentality.”

This section of the exhibition also provides the opportunity for visitors to experience Araki’s prolific output visually, through the installation of over 450 photobooks in the center of the gallery. This installation demonstrates the pure volume of his work but also allows visitors to see the wide range of his photography through a very different medium: one that is both more mass-produced and more intimate.

SD: Of his work, Araki has been called a madman, a pervert, and a ‘photography god.’ The exhibition encapsulates upon all of these things without solely leaning into one interpretation. What was the intent upon this curation of Araki’s work?

MM: From the rather unique institutional position of the Museum of Sex, we didn’t feel the obligation to be laudatory or critical of Araki as an artist. Our goal was to contextualize him, to introduce and educate visitors, while also being mindful of the way in which contemporary conversations about sex, power, and gender relationships are not in the same place now that they were even five or ten years ago.

Araki’s work has been hugely popular for many different reasons, just as it has been equally controversial. Because his photography directly intersects with expressions of sexuality, there’s no responsible way to present it inside this kind of institution without addressing the various cultures (geographic and temporal) in which it was created and recieved. Our primary goal was to have visitors understand the context of his work, and the forms of reception of it over the years—to give them as much of the story as possible.

SD: Russet Lederman posed a very interesting question in her review for Aperture, asking if feminists can embrace Araki’s work in this era of #Metoo culture. Can you talk about how you chose to contextualize Araki’s work to broaden its meaning and to remain grounded in this conversation?

MM: Lederman points out—rightly, I think—that one of the most complicated things about Araki in this context is his refusal to be any one thing. This obviously inspires disparate and even antagonistic reactions to Araki and his photography. It’s a completely valid reaction to question the visual language of Araki’s work, to call it objectifying, or complicit in a photographic history that treats women’s bodies a certain way—just as it is a completely valid reaction to understand that history and still find, as an individual, his work expressive of a sexuality that you find liberating, fascinating, or worthy of your attention. It is also important; however, to be aware that there are many factors outside of Araki’s photographic work itself that should be included in the conversation, which is one of the things we wanted to do—to the best of our ability, at least—in the exhibition.

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Komari from L'Amant d'aout (Suicide in Tokyo), 2002 Courtesy of Private Collection

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Journey, 1971_2017 Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery

We didn’t just want visitors to feel like they understood the reception of Araki’s work (i.e., is this pornography or not? Is this work sexist or not?), we also wanted to make available to them conversations about its creation (what are the conditions of these photographs coming into being?) and its contextualization (what can we learn about putting these photographs in dialogue with our current moment?).

In that sense, for the section dealing with the photographer-subject relationship, we wanted to enter into a broader conversation, one that includes the voices of his models, and one that also considers controversy about power dynamics, rather than simply about reception and interpretation of his work. We have the literal voices of some of Araki’s most significant models and collaborators enter into and shape the visitor experience. Models like Shino and Komari, for example, who both collaborated with Araki over years-long relationships that were romantic, sexual, and artistic, assert in these video interviews the nature of their interactions with Araki, and how they—in their own ways—felt empowered by or emotionally connected to the process of working with him. At the same time, we obviously felt the need to address an allegation of sexual misconduct that took place with another Japanese model on a commercial photoshoot in the early 1990s. After speaking directly with this woman over several weeks, we let her comfort-level guide how these allegations were presented in the show. Respecting her choices—remaining anonymous and leaving out certain details of the allegations because of the lingering fear of legal retribution—was paramount. But these choices also reveal how the power of an artistic brand and the power of celebrity are equally important factors for visitors to grapple with in the context of Araki’s rise to global popularity.

SD: The way this exhibition was contextualized with criticism, as well as outside perspectives alongside the work was masterful and truly innovative. Recently, there have been petitions from the public to include amending wall text on works of art in other institution that implore a power imbalance seen so often in art like with Araki’s photos where the artist refers to his camera as a ka-mara (Japanese slang for penis) and the female subject is a kind of passive muse. In this kind of cultural climate, do you foresee the viewer/public having more influence on the curation, with past and present being acknowledged?

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Lady Gaga, 2011 Courtesy of Longmen Art Projects

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Flowers, 1985 Courtesy of Private Collection.

MM: As an art historian, and now a neophyte curator, I’ve always believed that the public should speak back to their community institutions and that institutions should pay attention to what’s being said—they should engage in those conversations. As fraught as those moments can be, I’m heartened to see some museums doing exactly that and with more frequency (although, of course, there’s still a long way to go). I suppose rather than act as oracle about the way in which the viewing public might influence curatorial decisions, I’d add my voice to those that are interested in seeing museums being more transparent about those curatorial (and business) decisions at the outset, and in general, especially if it takes the form of institutions examining their past and current practices, reframing exhibitions and works for contemporary conversation, and acknowledging these issues through progressive and impactful educational programming.

SD: Araki has been a courageous pioneer of his art and vision. As mentioned in the exhibition, Japan has obscenity laws where genitals must be blurred or pixelated. It was interesting to learn that due to censorship in this country some of his work was not permitted in this collection like "Tokyo Lucky Hole"- 1985 and had to be represented by a reprint. In combing through the photographer’s archives, how did you make your photo selection? Did you encounter your own kind of censorship or ever feel a photo was too sexually graphic?

Juergen Teller Araki No. 1, Tokyo 200 © Courtesy of the Artist

MM: (A small correction: the photograph from the "Tokyo Lucky Hole" series that was stopped in customs is not a reprint, but in fact was just sourced through a different route!)

It’s interesting to think about self-censorship in the context of this institution and this exhibition, absolutely. Speaking only for myself, I certainly felt a degree of freedom in knowing that there were no concerns institutionally about what might or might not be “appropriate” in terms of explicit sexuality.

I think for someone like Araki, who is a sort of compulsive image-maker, Mark and I both felt it was important for visitors to be able to access the range of his work, while still staying faithful to the goals of the exhibition. Araki’s expression of sexual desire and everyday life are inseparable, and his expression of this “lust for life,” as it were, isn’t just relegated to photographs of bound and naked women. There are his photographs of sky-scapes, Tokyo side streets, the people of Japan, flowers, toy dinosaurs, his late cat Chiro, and so on and so on. Starting from our initial major loan, we were able to identify the overarching thematic structure—and from there we could start to see which potential series or prints might be ideal to help visitors see how Araki expresses his view of the world from behind the camera lens.

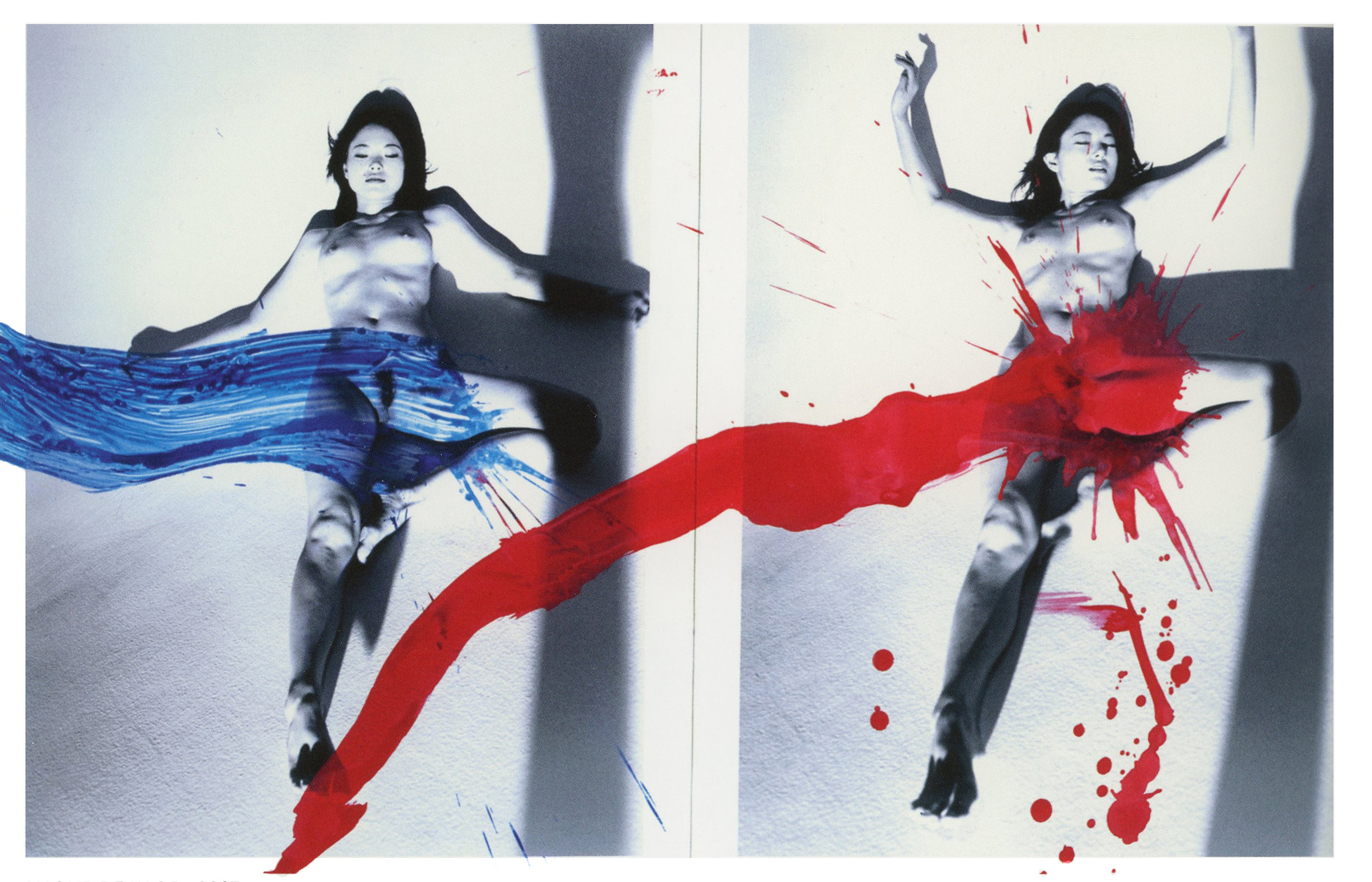

© Nobuyoshi Araki KaoRi Love, 2007 (Diptych) Courtesy of Private Collectio

SD: There is a great beauty to Araki’s photos, as well as in his unique ability to portray sexuality through the subliminal. The sex is explicit but never dirty. It was interesting to see the juxtaposition of the larger High Art photos with the wall of a hundred plus Polaroids, which evoked an overall different experience than in anything else in the collection. How did size as well as different mediums and techniques factor into your presentation of sexuality within these photos? To what effect did you feel responsible for shaping or directing a response to what was being depicted in a photo?

© Nobuyoshi Araki , Colourscapes, 1991 Courtesy of Museum of Sex Collection.

MM: In general, Mark and I both felt that diversity of form was important. Practically, a lot of Araki’s printed photographs are very large (often 40 x 60 or larger), and they can be sort of domineering if not given the opportunity to breathe in the space. And while we didn’t necessarily mind if a particular work—or set of works—were potentially confrontational to the viewer, we also didn’t want visitors to end up feeling claustrophobic.

Araki also usually works with multiple cameras simultaneously on any given photoshoot or project, and each camera will produce an obviously different product. As you say, it’s very true that Araki’s polaroids feel innately different than his large scale prints, especially when they’re presented in bulk like his Pola Eros series. They suggest a different kind of intimacy, and often end up feeling sort of illicit. But these different techniques and different camera choices reveal something about Araki too—leaving out the Polaroids would be sort of disingenuous for an exhibition that was really striving to introduce Araki’s multiplicity, his volume, and his range. The choice to center the photobook installation on the second floor of the exhibition came from the same impulse.

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Winter Journey, 1989-90-2005 Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery.

© Nobuyoshi Araki, Colourscapes, 1991 Courtesy of a Private Collection

SD: It was fascinating to read that the Museum of Sex is the first institute in the U.S. confident enough in their abilities to respectfully feature Araki’s work. With a seismic shift in attitudes towards sex, do you foresee at this time more Araki exhibitions, as well as place in the art world for more work that explores sexuality in this tradition?

MM: I’d love to see more exhibitions address these issues, and not only within the context of Araki, or even Japanese photography! I’m not sure that every institution has the same kind of unique and unusual positioning as the Museum of Sex had in tackling Araki, but I’m deeply grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with them on this project, and for the positive and thoughtful responses to this particular exhibition. I also hope that visitors who have responded to Araki’s work might also be interested in artists who have been inspired by him (either in kind or in opposition), especially female Japanese photographers like Nagashima Yurie, HIROMIX, and Ninagawa Mika. And overall, I suppose I do believe that there is increasingly more room in the world for exhibitions that attempt to tackle fraught topics without alienation or sensationalism.

© Nobuyoshi Araki Untitled (Painting Flower), 2005 Courtesy of Anton Kern Gallery