Exhibition Review: Eugene Richards - The Run-On of Time

“Crack Annie,” Brooklyn, 1988. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

Review by Matt Fink

In the arts, context plays various roles, be they to make sense of a work, enhance and deepen its meaning - or construct around its edifice the leaden scaffolding of useless hearsay. For instance, it may be interesting to know that Beethoven composed his 3rd symphony as a tribute to his idol, Napoleon Bonaparte, but it’s far from being essential to the listener’s experience.

On the other hand, an expansive, career retrospective of the work of photographer Eugene Richards (September 27-January 6 at the Bowery’s International Center of Photography) may not need context for its impact, but that which was offered by the artist himself during a press tour of the installation gave undeniable heft and dimension to this, a tour-de-force of his towering contributions to 20th and 21st Century photography.

Of course, artists aren’t bottles of complimentary hotel shampoo; they don’t automatically accompany shows. But fortunately for those not invited to the press event, each of the handful of capacious rooms comprising Richards’ “The Run-On of Time” comes with a handy summaries.

Doll’s head, Hughes, Arkansas, 1970. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

Grandmother, Brooklyn, 1993. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

Richards began his presentation at the beginning, describing his entry into the world of photography while volunteering with the Kennedy Administration’s poverty-relief VISTA program in Civil Rights-era Arkansas.

“I started photographing very tentatively and very nervously because these were people I didn’t know, and they sure as hell didn’t know me,” said Richards. “They didn’t understand this bald white guy coming into their homes.”

For a nascent documentary photographer - and a white man from Dorchester, Massachusetts - interacting with poor black people in the charged atmosphere of 1960s South was something of a trial by fire.

“One of the problems working in a place like this is that, at first, people would treat you with incredible deference,” explained Richards. “You’d ask, ‘Can I come into your home,’ and they’d say, ‘Well, I have to let you into my house.’ It was a very difficult learning experience for me to get to the point where I could make true friends.”

Dustin Hill with his daughter, Mineral, Illinois, 2008. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

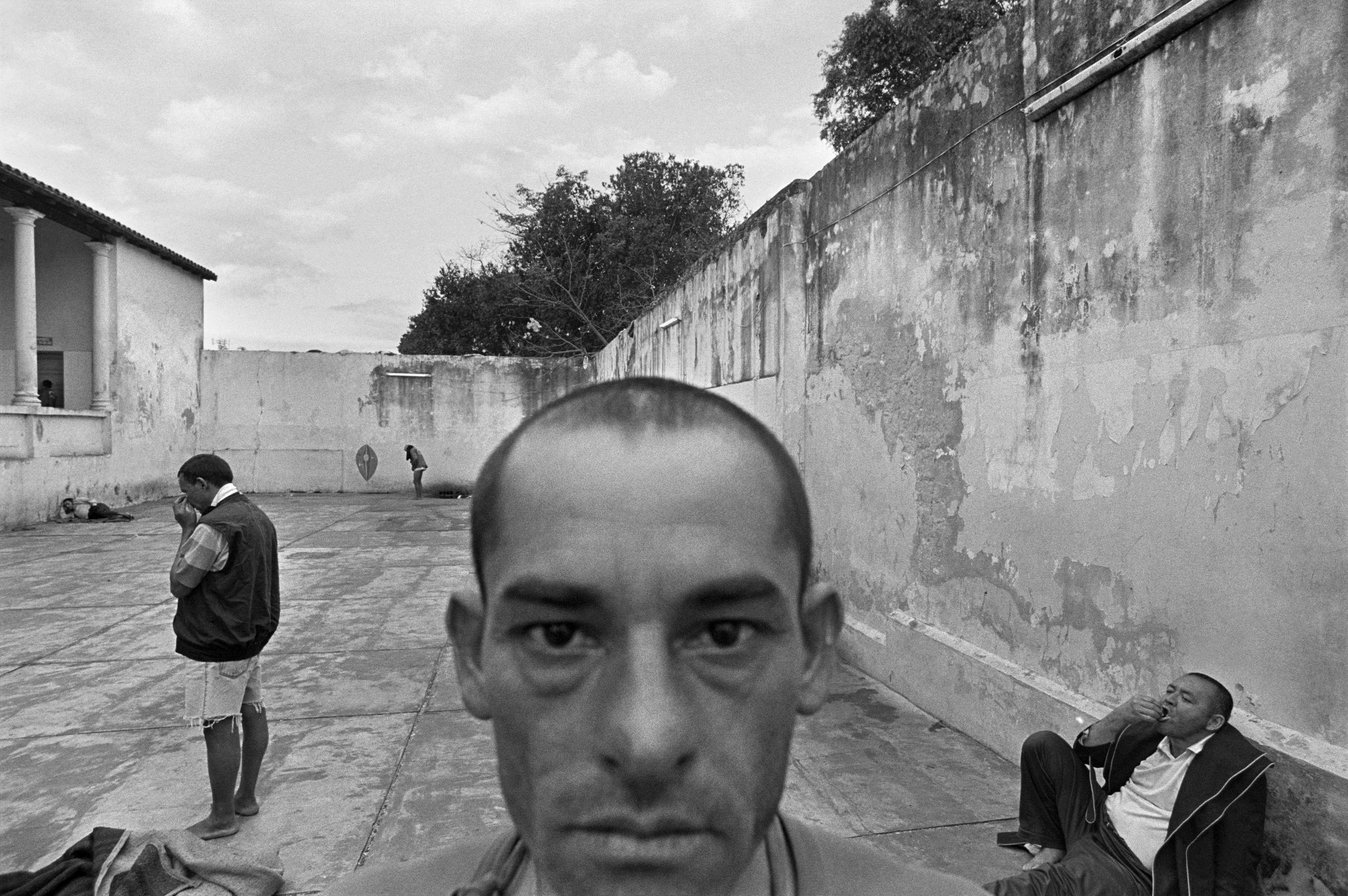

The old ward, Psychiatric Hospital, Asunción, Paraguay, 2005. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

Later, in the late-80s and early-90s, Richards became acquainted with members of a New York gang.

“She’s one of my heroes,” said Richards, indicating a photo of a wane, startled-looking white woman with straight, hay-colored hair. “She was a gang girl, but she’s a hero in the sense of being someone who rises above who they are. She protected me in the gang.”

He paused before adding, “She’s a person who went on to do terrible things.”

Richards’ photography is so visually compelling it can sometimes overshadow his intent and point of view, both of which are informed by his concerns about social justice, poverty, race, class and gender. This begged the question - put to him after the tour was over and he was hanging around being button-holed by eager members of the press - of whether or not he fights an interior moral battle over his own work, which could be characterized, correctly or not, as aestheticized misery and suffering.

“Not until I end up in a place like this, where [the images] are suddenly on the wall,” answered Richards. “On one hand you’re glad [that they are being shown], but there’s a discomfort level to seeing human experience on the wall and looked at, possibly, without context, and to be applauded for something that most of the people in the photos are not applauded for.”

Still House Hollow, Tennessee, 1986. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

Back from prison, Shantytown, New York, 1986. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

Person to person, Richards strikes a deft balance between confident, upbeat self-appraisal and humility. These are qualities which may have come in handy in his work: only a person possessed of both a certain level brazenness and self-effacement could successfully co-mingle with, among other people, gang members, patients at questionably-managed Latin American mental institutions and at least one constituent of the KKK.

Qualities of humility and confidence are also reflected in Richards’ general view of his own work: “I can say with great confidence that the pictures are the truth at the moment, but beyond that I don’t go to far.”

Snow globe of the city as it once was, New York, 2001. Gelatin silver print.

Collection of Eugene Richards. © Eugene Richards

International Center of Photography, 250 Bowery. Open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursday, closed Monday.

Tickets at the door or on the ICP website: 14 general admission, 10 for students and 12 for seniors. Children 14 and under enter free.

For more information, click here.