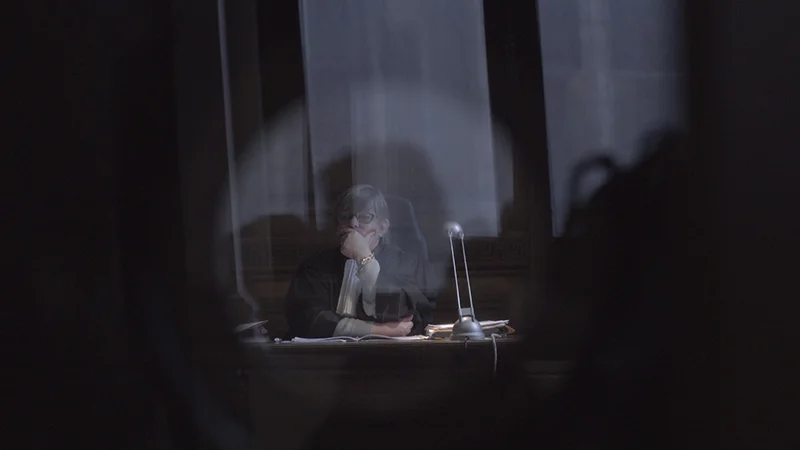

CAREY YOUNG: The Peeping Tom

Portrait by Steven Probert © Carey Young. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Interview by Andrea Blanch

MUSÉE MAGAZINE: There is an element of voyeurism to the work due in part to your clandestine method of filming. Scenes of the courtroom are viewed through apertures and key holes adding to the institutional obscurantism. What added meaning did this technique provide for your work?

CAREY YOUNG: Almost all the courtroom doors at the Palais de Justice in Brussels contain circular windows, through which one can view the trials in progress. This design expresses the idea of fairness in legal trials, it indicates that there is a transparency to the process. In order to create my video piece Palais de Justice (2017), I shot a lot of footage of trials in progress through these windows. They became framing devices, like the vignette in portraiture, and also they remind us of lenses and the cinematic. Also, the furtiveness of these shots calls to mind the ‘peeping tom’ within the filmic genre, and the idea of voyeurism. For me that was a potent starting place to consider law, and especially the idea of women in relation to law and power.

Carey Young, Palais de Justice, 2017. Single-channel HD video (from 4K), 16:9, colour, quadrophonic sound, 17 min 58 secs

The windows also allowed me to shoot with a 360 degree view, because they captured reflections from the corridor behind me, as well as the courtroom scenes. Thus, we are aware of events behind the cam- era, as well as the trials proceeding in front of us. This glassy appearance, and the many layers of glass and reflections in the image, created a painterly, ‘floating’ aesthetic which also adds a sense of unreality. And already, when one thinks about courts and trials, one is probably more influenced by images from TV and cinema than by real experience.

Our idea of the courtroom is largely a construct formed from fictions like these. I felt there was real potential to put real judges and real trials on camera and for this to feel surprising. One initially has no idea if the situation is real. And then the action unfolds, and the sheer number of lawyers and judges I captured, and the events taking place suggest this is reality. It has a verité feel, of something unstaged, even if the idea – of women judges in control of a court or perhaps an entire legal system, or perhaps the very idea of justice, is like something from science fiction.

Carey Young, Palais de Justice, 2017. Single-channel HD video (from 4K), 16:9, colour, quadrophonic sound, 17 min 58 secs

MUSÉE: You’ve mentioned that the aesthetics of the law is part of what draws you to create projects like “Palais de Justice.” As you express, the law is a rather unutilized source of fodder for art and photogra- phy. Could you expand upon your thought process and impetus for doing works like these?

CAREY: Law has often been seen as the antithesis of art, but I’ve been more interested in the ways in which art can shed light on law, and conversely, how law could be used to analyze art, or to create ‘anti- art’ via legal means. I am not talking about ‘art law’ – intellectual property or appropriation, for example – these aspects don’t interest me as much.

Carey Young, Palais de Justice, 2017. Single-channel HD video (from 4K), 16:9, colour, quadrophonic sound, 17 min 58 secs

What I’m interested in are the wider questions, like what is law as a power structure, how do we per- form within it, why do we turn to it, and what values are embedded in its language and rituals? How does it make us feel? What does it sound like? How and why does it attract us? Since law is one of the biggest power bases in society, it absolutely needs to be critiqued, especially by artists. Yet it is so little understood. As well as being artistically interesting, such work can contribute to the public understand- ing of law and to notions of possible change.

Also, one can approach artistic subject matter – the sublime, the portrait, the site – by viewing it through legal means, and this is a way to get outside the confines of art orthodoxies. For example, one can consider the sublime by looking at outer space law; one can explore ideas of site and landscape via considerations of land law, with all its concerns about zoning and borders. There’s just so much potential there to make thought-provoking art, if one is willing to do considerable research. I spend a lot of time in law libraries. If you wander around a law library with artistic ideas and an open mind, you’ll eventually find material...

MUSÉE: What do you believe is the relationship between the power of art and the artist and the more formal power expressed through the law?

Carey Young, Palais de Justice, 2017. Single-channel HD video (from 4K), 16:9, colour, quadrophonic sound, 17 min 58 secs

CAREY: This is a huge question! In Palais de Justice I approached this by using shots where the judges appear to make eye con- tact with the camera. In actual fact, they did not see me or the camera, and had no idea they were being filmed, but the shots really do look like a stand-off between judge and artist: a stand-off of power, between ideas of judgement and the possibility of representation. I want to conflate these two things and ask the viewer to compare ideas of power here, artist versus judge, which is also a dialectical relationship.

And then in the act of looking the viewer has their own role as judge. In the video, I depict a young girl sketching the building. In a sense, this shot also refers to me. She is trying to convey the building, yet nevertheless, she creates her own interpretation.

MUSÉE: Some of your past works have similarly focused on various branches of the law such as land, contract, intellectual property, and the laws governing outer space. What is your relationship to the law? How did this attentive interest develop, and what branch or area of the law did you have in mind when creating Palais de Justice?

Carey Young, Palais de Justice, 2017. Single-channel HD video (from 4K), 16:9, colour, quadrophonic sound, 17 min 58 secs

CAREY: I became interested in the law in 2001, when I met a patent lawyer and learned about ‘prior art’. This is a series of images within a patent application that is used to offer proof that the invention is original by portraying something that already exists and is similar. I loved this idea, which sounds so much like a weirdly inverted version of curating.

Patent law was also interesting in its attempts to monetize and corral creative ideas – and that had a parallel with the instrumentalization and corporatization of art and culture more generally. And from then on, law appealed to me, as a system of rules that could be played with, and as a kind of choreography that one could use to propose new relationships between objects, people and sites or spaces over varying periods of time, from the period it takes to read a sentence to a whole lifetime. Contracts, for example, can be seen in an abstract way, as a form of promise or exchange. It is up to the artist to determine what is exchanged or promised and between whom, and that is an exciting set of parameters to work with.

Carey Young, Palais de Justice, 2017. Single-channel HD video (from 4K), 16:9, colour, quadrophonic sound, 17 min 58 secs

Many of my works have also involved lawyers very closely in their creation, for example, to help me draft the wording I use in my performances, videos and installations so that the works are ‘works of law’ as well as ‘works of art’. These works are known for being creative and experimental within the law, they break with conventions and are at the margins of what is legally possible.

My relation to the law is that of the outsider. I have no formal legal training, but I’ve referred to legal text- books and philosophy/critical theory relating to law (Agamben, Foucault etc) for 15 years. Most lawyers are specialists in one field or another, but I am a generalist and have dipped in to many different legal areas, including land law, air and space law, inheritance law, the law of the sea, intellectual property, criminal law, legal fictions and contract theory. That makes me pretty feral in the legal domain, a bit of a weirdo!

To read the full article, click here.