An Interview with Spotlight Artist: Kyle Meyer

©Kyle Meyer

Interview by Matt Fink

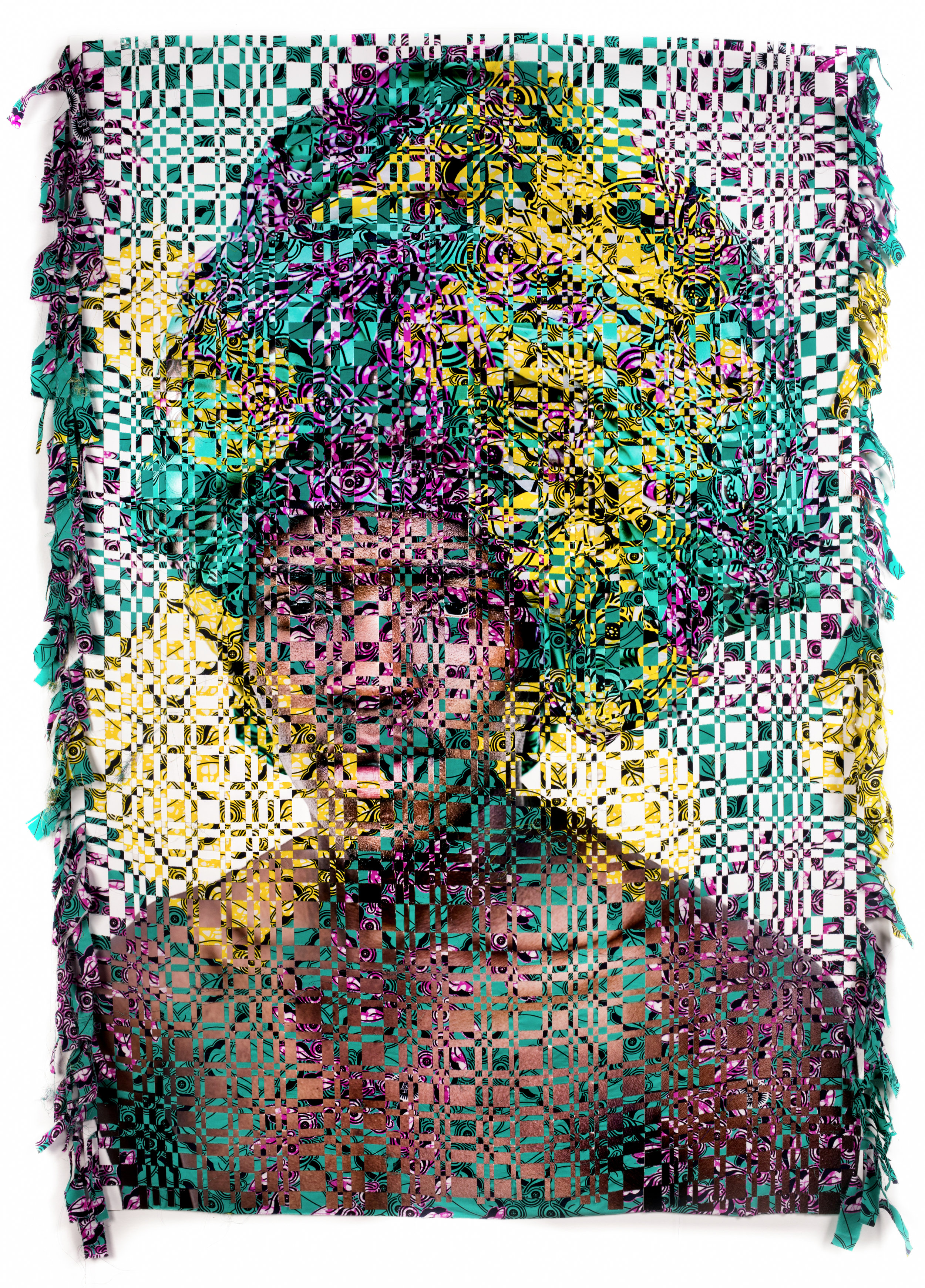

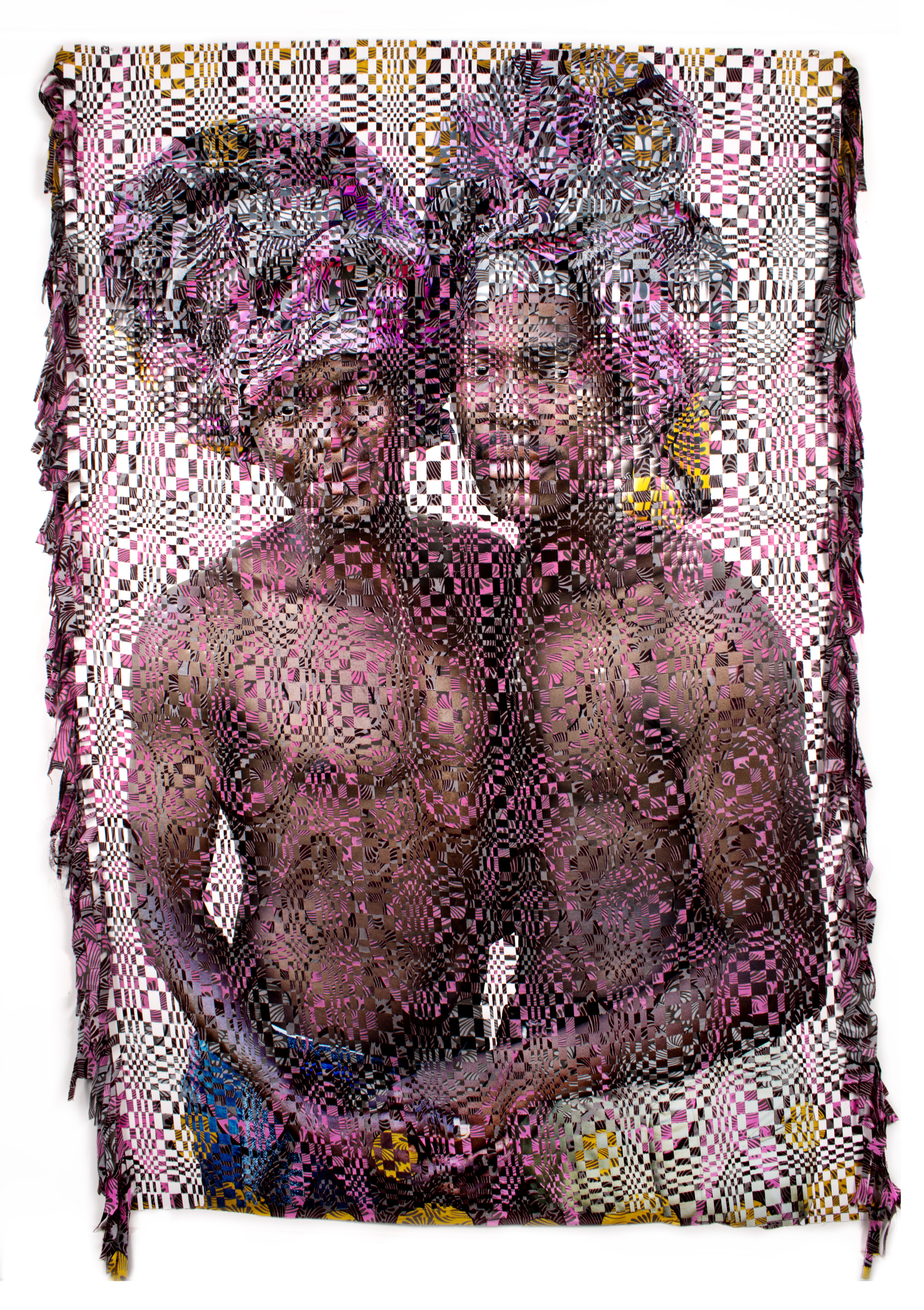

Kyle Meyer is an American artist who uses a variety of materials and techniques. His latest work, created while in Swaziland on a Brandeis University grant, is called Interwoven. It consists of portraits of gay local men clad in women’s headdresses; these decorative fabrics are then woven into the prints where they appear, creating vivid commentaries on gender norms and the marginalization of gay men.

Matt Fink: Where are you calling from?

Kyle Meyer: From my studio, a converted garage two hours north of the city in the Catskills. I spend most of my time up here.

Matt: So you’re no longer in Swaziland?

Kyle: No, but I go back a lot. I’ve been there twice this year, and I’m planning a trip this January.

Matt: Why don’t we go back to the beginning. How did you become interested in art?

Kyle: I didn’t know I wanted to be an artist until college. I moved to the city right after high school and enrolled at City College two years later. The first couple of classes included an art history course, which blew my mind, and then my professor encouraged me to take a 2-D class. After that, I change my major to a BFA.

Matt: How did you end up in Swaziland?

Kyle: Once I graduated from City College, I received a grant from Brandeis University to go to Swaziland to document factory workers. I worked in a candle-making factory, a basket-weaving company, and a glass-blowing company. By being there, [the workers] became my family. I was working with them, hearing their stories and learning their crafts. That’s where the weaving came from: I was working for this basket weaving company called Tinstaba, who make their products from a specially dyed grass, hand woven. I was working with women within the factory and they were teaching me how to make them. Then at my home, there was no cable or internet, so I was taking these crafts I learned during the day and applying it to my own practice.

©Kyle Meyer

Matt: Prior to that experience did you know how to weave?

Kyle: No.

Matt: So you learned on the job?

Kyle: Yes. Going there I had no idea I wanted to weave, but once I got there I was able to more closely connect with the workers through weaving, and then I fell in love with it! The first week I was there I was like, “This is what I want to do.”

Matt: For the uninitiated, Swaziland is a tiny, tiny little country, not very well known. Could you give us the thumbnail version of its history?

Kyle: It’s a landlocked country in South Africa, run by a king who has, I think, 13 wives. It’s a polygamous society whose major religion is a form of Christianity called Zionism [not related to the Jewish movement], but they also practice African traditions: going into trances, speaking in tongues, and a kind of black magic called Muti.

©Kyle Meyer

Matt: When you went to Swaziland, what were your impressions of the attitudes there towards the LGBTQ community?

Kyle: Well, it’s not as if they’re rounding up the community and jailing them. It’s more systematic oppression. If you’re spotted as LGBT, you’re going to have a hard time getting things such as proper health care, education, or a job. A lot of people are closeted as a result and there’s a lot of violence against the LGBTQ community on the streets. A lot of my subjects have told me about being raped. One, in particular, was given HIV in the process. It’s quite an intense situation.

Matt: Who were the people who participated in Interwoven and how did you connect with them?

Kyle: When I first started the project six years ago, it was me photographing my friends. Then they introduced me to people, and those people introduced me to others. Now I’m working with a couple of organizations who do outreach, and NGOs who deal with LGBTQ rights. They take me to more rural areas. Interwoven started in the major cities, such as Mbabane and Manzini, but now it has extended further out. I’m really trying to focus on the more rural individuals because they’re not being heard and don’t have proper health care or education.

Matt: So, Interwoven is an ongoing project?

Kyle: It has been, yes. I still have more work that’s being made, but I want to take a break from it and work on some other things. I’ll always go back, though - it’s my second home. I have a ton of “family” there.

Matt: When was the first time you went there?

Kyle: In 2009. I wanted to be in the country with the highest rate of HIV, and being a gay man and having not experienced the 1980’s AIDS epidemic, I wanted to essentially understand what it was like. I started working in the factories, I documented the religion and the LGBTQ community, and then really branched out into the culture.

©Kyle Meyer

Matt: How did you connect with the LGBTQ community and were many of its constituents in the factories?

Kyle: No, none of them were in the factories. I’m a gay man, so I met people that way.

Matt: Is there a connection between Interwoven and the AIDS quilt?

Kyle: Somebody else made that reference, too. It never occurred to me. The inspiration for the project was just photographing these men and then taking the craft [weaving] that I had spent so much time learning to bring them together.

Matt: Could you describe the technical process of making one of Interwoven’s pieces?

Kyle: When I go to photograph somebody I take about 40 pieces of fabric with me and the sitter gets to choose whatever he wants. A lot of it comes from the colors and patterns they like. Then I sit and chat with them a bit, and decide how I want to fashion the headdress on them. Once the headpiece is on, I take a picture. That photograph is then printed and cut with an Exacto knife and a ruler, after which it’s hand woven with the headdress fabric. The idea was this: the headdresses feminizes the man and the male body. A lot of people, think the subjects are women when they see the work because a man would never wear a head wrap. Matt: So the whole point is to subvert gender stereotypes.

Kyle: Yes.

©Kyle Meyer

Matt: The gay men you worked with, did you meet with a lot of trepidation and fear when you approached them?

Kyle: Yes, but they know what they’re getting themselves into. However, there are some men I won’t weave, because I could tell there was anxiety there. I never want to pressure anybody to do it, or take advantage of anyone. I also have a lot of anxiety as the creator of the project. Every time I go back to Swaziland, I’m fearful. The King and the new prime minister have called homosexuality, “satanic.”

Matt: Have there been any instances of violence or intimidation against you?

Kyle: No. I photograph in safe spaces. That’s the thing: I’m very visible now, with the project getting a lot of attention. The more it gets out there, the more I’m exposed. So, I do have a lot of anxiety going back there.

Matt: You’re weaving the photos themselves with the headdresses the subjects are wearing?

Kyle: Yes. That’s very important, that it was on their body. It has their DNA. It could have hair follicles, their sweat. They are the weaving.

Matt: So, having knowledge of how the pieces were made is a very important part of the viewing experience. Kyle: I think it’s very important that people read about what is being shown. It’s important that they’re reading about the project and my experience and how I got to this. It took essentially ten years to come up with. I’ve become a big part of the community, and I give back. People are always quick to judge. They don’t want that next level of information that really solidifies the project.

Matt: Looking over some of your other work, Unfamiliar Family seems very related aesthetically to Interwoven.

Kyle: That project is made of photographs of my great-great-grandparents. They are images from the late 1800s and early 1900s that I scanned and then wove with fabric that I dyed using my own body during performance-based work. [The fabric] essentially became a skin, with my own DNA woven through these images of people whom, while family, I don’t know anything about. I made that during grad school.

Matt: Where did you go to grad school?

Kyle: Parsons. I was in the photo department, but I was weaving the entire time.

@Kyle Meyer

Matt: You mentioned using your own body to dye the fabric. What did you use?

Kyle: During performances, I would dunk my feet into buckets of dye and walk on the fabric. Other times, my body was wrapped in fabric and then had these bags of dye popped over me. There are several videos on Vimeo to get an idea of some of these performances.

Matt: In light of the government of Swaziland’s negative attitude towards the LGBTQ community, how do you feel about the prospect of Interwoven becoming more widely known?

Kyle: I’m scared. I’m very nervous. The project has gotten to a place I didn’t expect it to. It started as me documenting my friends and now it’s become larger than I was expecting. There’s a lot of anxiety around it being more well-known. However, in my next projects, I’m still going to be doing political, LGBTQ work. This is just the beginning.

Matt: Can you give us a little taste of what might be coming?

Kyle: For the next project, of which I’m in the research phase, I’m looking at spaces where there have been violent acts against LGBTQ persons throughout the United States. What I’ll do is cover the space [where the incidents occur] with dyed fabric, photograph it, and then that same fabric will be woven through the print. It’s about remembrance. A lot of acts against the LGBTQ community go unreported or they’re reported and then forgotten after a few days.

Matt: So, it’s essentially the landscape version of Interwoven?

Kyle: Yes. It’s still-life and landscape. I’m really interested in working on something where I’m remembering the person. Each piece will include a text element where you can read about the affected person. To really get it going, it’s going to take several years. The one test piece took me three months to make.

Matt: Going back briefly to the factory, what are your thoughts about the fact that you’re a “First World” artist who has the luxury of going to a factory and engaging in what are, in reality, backbreaking labors, and then having the ability to leave at any time - whereas for the workers it’s their livelihood.

Kyle: Going there, I was very aware of how privileged I was to be there. The factory workers, as I said, became my family. I was working with them every day and listening to their stories. That’s the major thing; they want to be heard. To have somebody come and sit down and ask how their life is going. A lot of their stories are intense. I was humbled every day I went there and listened to them. Yeah, it’s crazy that I can leave, but I go back a lot, and when I return to the factories I see my family.

Matt: It sounds rewarding and very emotional.

Kyle: It’s extremely emotional. I feel lucky every day of my life that I’ve been granted this opportunity and these experiences. Every day that I wake up and go into my studio to weave is a beautiful day. I’ve seen a lot of really crazy stuff in Swaziland, which I won’t go into, but being there has woken me up as a person. I thank God every day that I’m alive and that I get to do what I want.

For more details and images please click and view Musée Magazine Issue. 21. Risk.